Witness Accounts

In 1970, plaintiffs filed a Motion for Order Precluding Defendants from Opposing Claims, including fifty written testimonies from Hartford residents about police mistreatment and violence. These stories provide proof of plaintiffs’ complaints against the HPD, intending to discredit any arguments against them. The testimonies range in length and kind, describing a range of incidents from being stopped without explanation to being brutally beaten, unprovoked, by Hartford Police Officers. A continuity emerges between the simplicity of Hector Gonzalez’s complaint—“I think it was brutality for they pushed us into the wagon without taking into consideration that a human being should not be pushed”—and the complex pattern of harassment and violence that Jacqueline Harvey and her family were subjected to (see below).

In 1973, in preparation for a trial which never occurred due to the settlement agreement, plaintiffs submitted a new list of 195 witnesses with a brief description of the testimony each one could provide. The list includes a range of roles passionate about police accountability: city council members Allyn Martin, Collin Bennett and George Levine; members of the clergy, such as Reverend Charles Pickett; members of the HPD, such as Clarence Hyde; progressive city officials Arthur L. Green and Arthur Johnson; influential local organizers, such as Maria Sanchez and Leroy Clemons; and many individuals who were not otherwise public figures, whose stories were given the same platform and evidentiary weight as those who were.

These witness statements are a unique resource for understanding the norms of policing in Hartford during this time, outside of the narrativization inherent to mainstream media coverage. Across this significant archive of harm, the most undeniable pattern that emerges is the HPD’s habitual exploitation of different kinds of vulnerability; beyond the baseline claims of ethnic discrimination lined out in the case itself, it is clear that the HPD often targeted the very young, women, families (specifically interfering in the relationships between mothers and sons of color), those who spoke no english, and the physically injured.

How can the reader engage with these stories, a half century later, bearing witness to the survivors who never spoke their words in court? The statements are offered in full so that they can be felt on their own terms. Certain threads of open-ended analysis are offered throughout, intended as suggestions for ways of seeing. It is highly recommended that the reader look through the full pdf of original statements from 1970, and testimony summaries from 1973, which is available to view here.

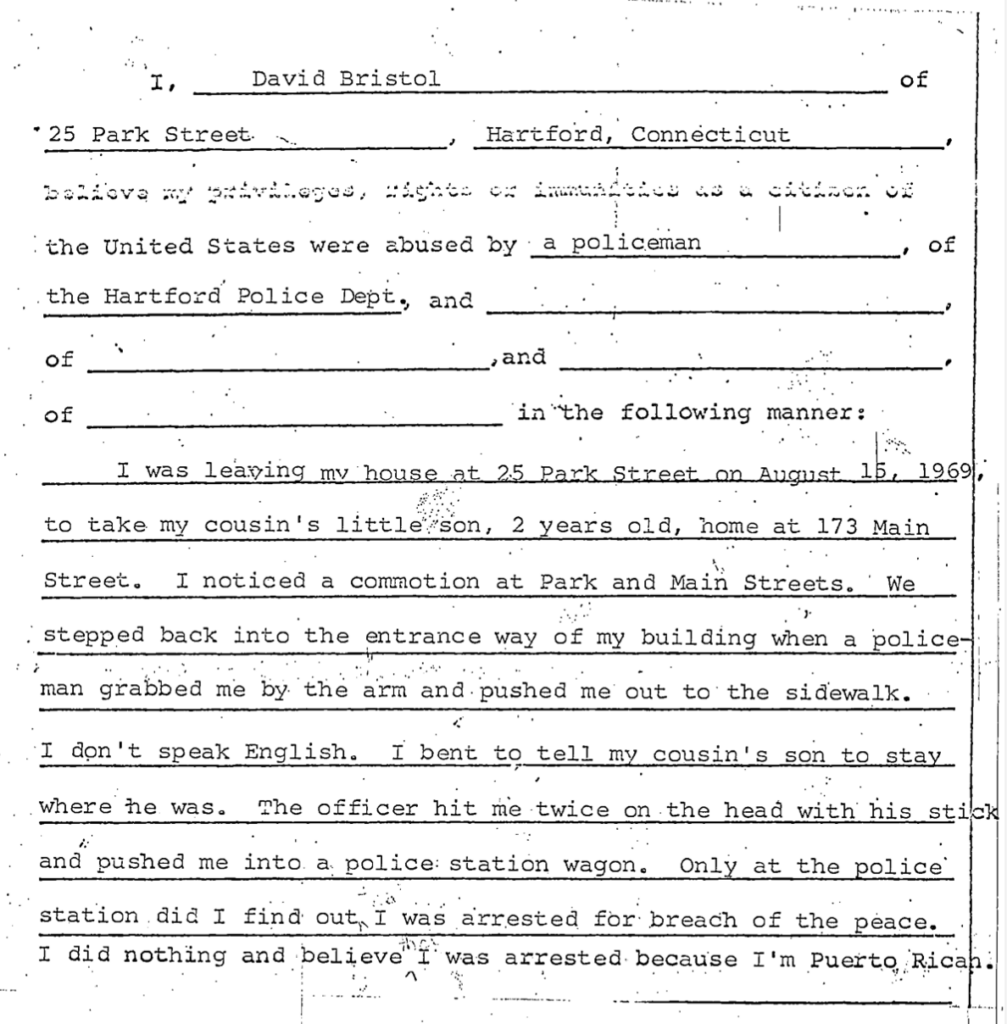

Many witnesses report being arrested while walking down the street, for no apparent reason, detailing that they could not communicate with the arresting officers because they spoke no English. These stories often occur during the summer and early fall, which was the season of civil disturbances in the late 60s and early 70s, but are unrelated to the disturbances themselves. They often occur in daytime, and concern someone walking alone, or with a child. Sometimes there is a disturbance in the area, sometimes not. David Bristol provided his story, in translation but otherwise a direct account.

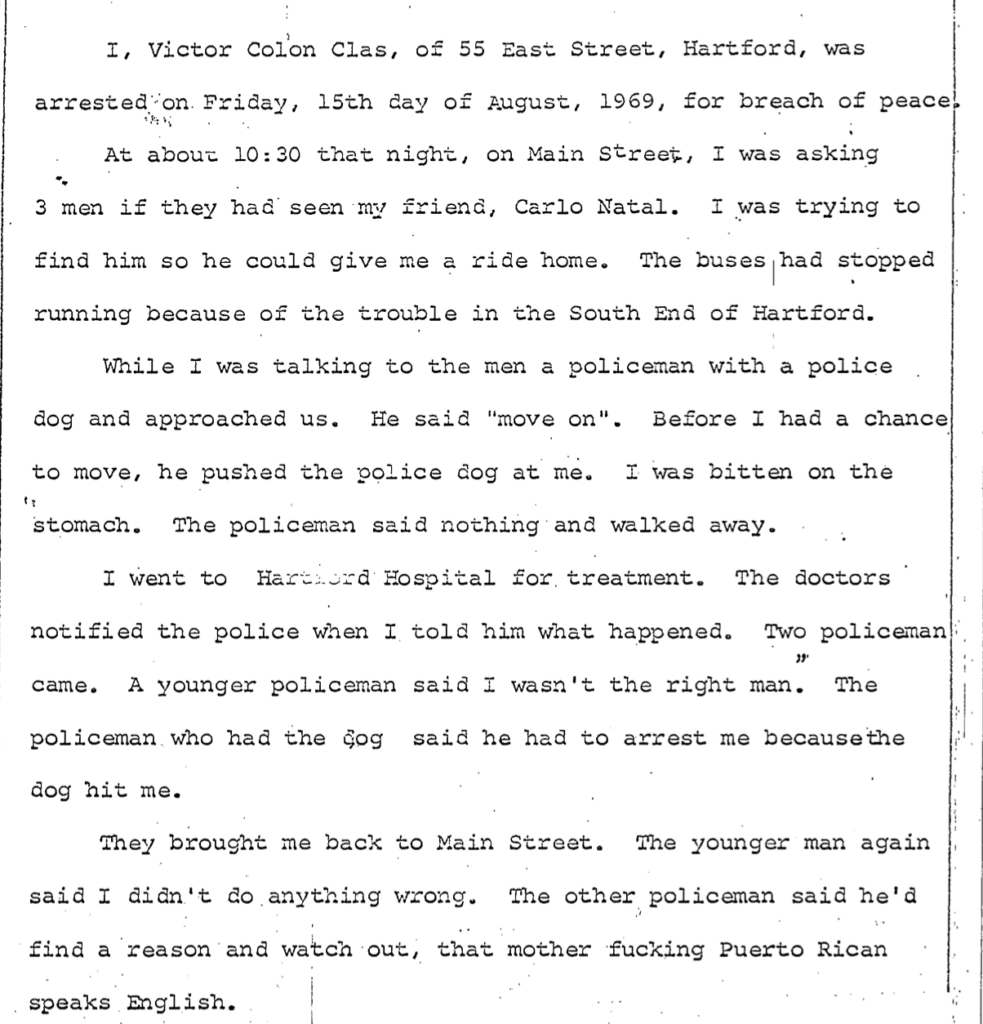

The testimony of Victor Colon Clas provides further insight into the HPD’s pattern of targeting Puerto Rican immigrants who spoke no English.

This HPD officer was threatened by the fact that Clas spoke English, implying that he expected Puerto Ricans not to. It was standard practice for officers to exploit this powerlessness, enabling abuse without recourse. Pictured is Carlos Natal showing a dog bite on his leg. Natal was a friend of Clas’ who was also attacked while trying to help Clas during the incident recounted above.

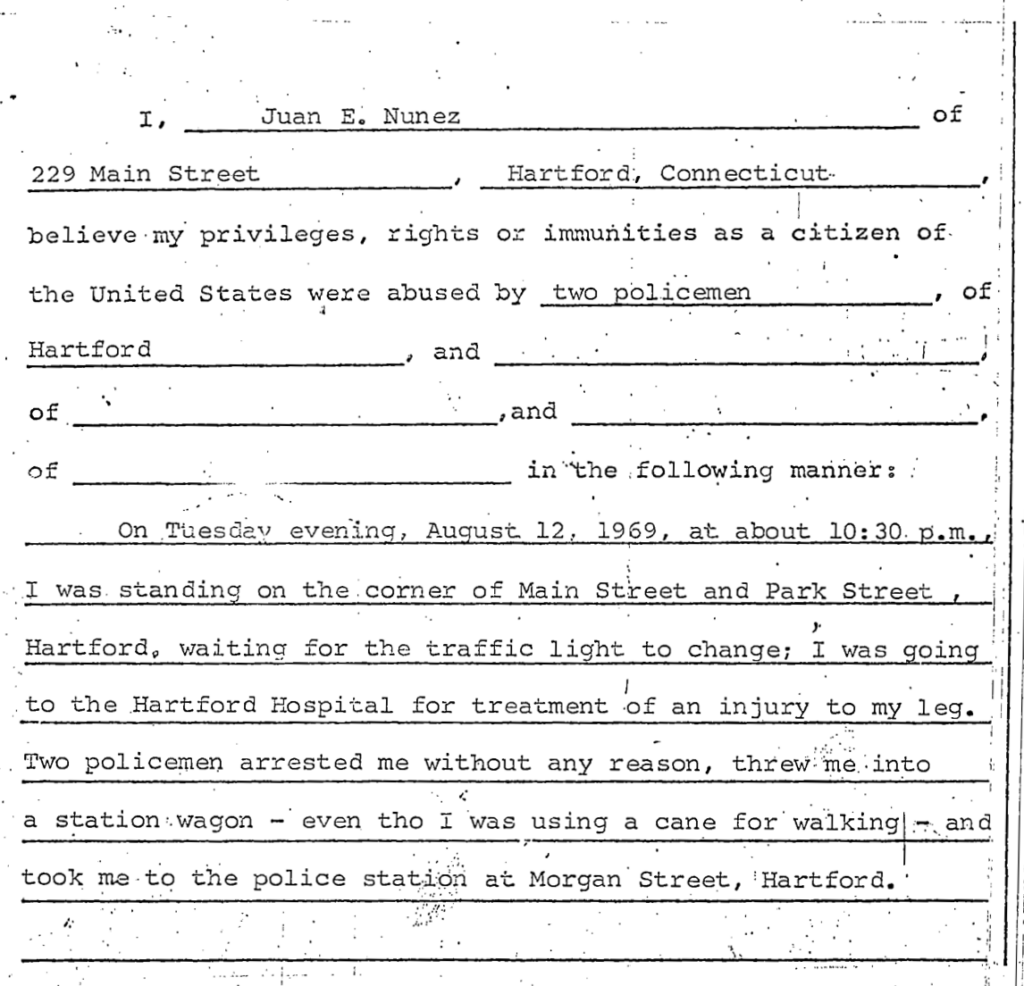

The archive includes several stories of people with physical injuries being further injured by the police. Consider the testimony of Juan E. Nunez.

By harming those who need protection most, it is clear that the late twentieth century HPD’s pursuit of “public safety” excludes Black and Puerto Rican citizens. These groups are not part of the “public” the HPD imagines itself to be continuous with: Hartford’s White and middle class communities. As explained throughout our timeline of Cintron v. Vaughan, an individual officer’s race does not change their alliance with the imagined public that is worthy of police protection.

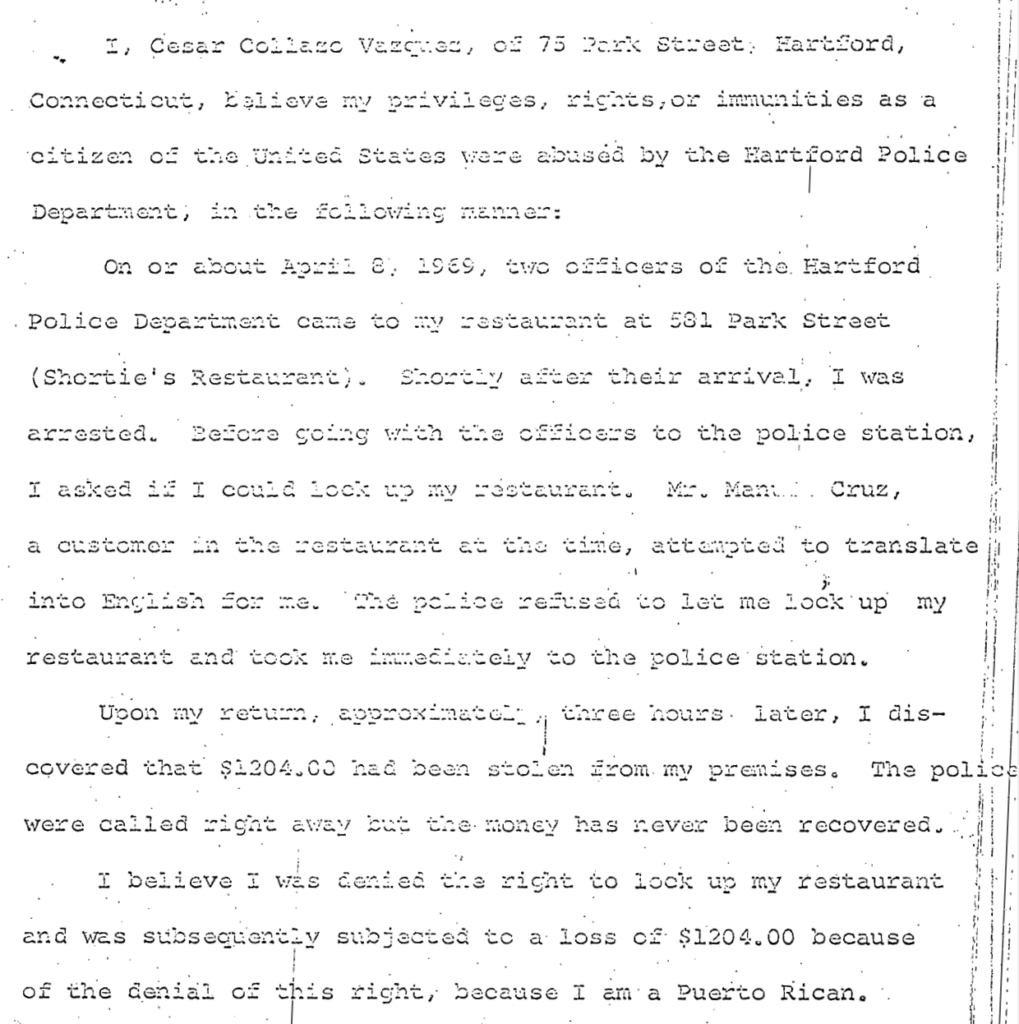

Beyond an injured person, there are other prototypical figures who are the objects of police protection: women, children, and victims of crime. All of these categories were harmed without shame by Hartford Police Officers during this era. Beginning with the last of these, read the story of Cesar Collano Vazquez.

Note that it is implied that Vazquez, like Bristol and many others, did not speak English. The dark irony is obvious; after being robbed, Vazquez had to call the same police that had effectively enabled the robbery.

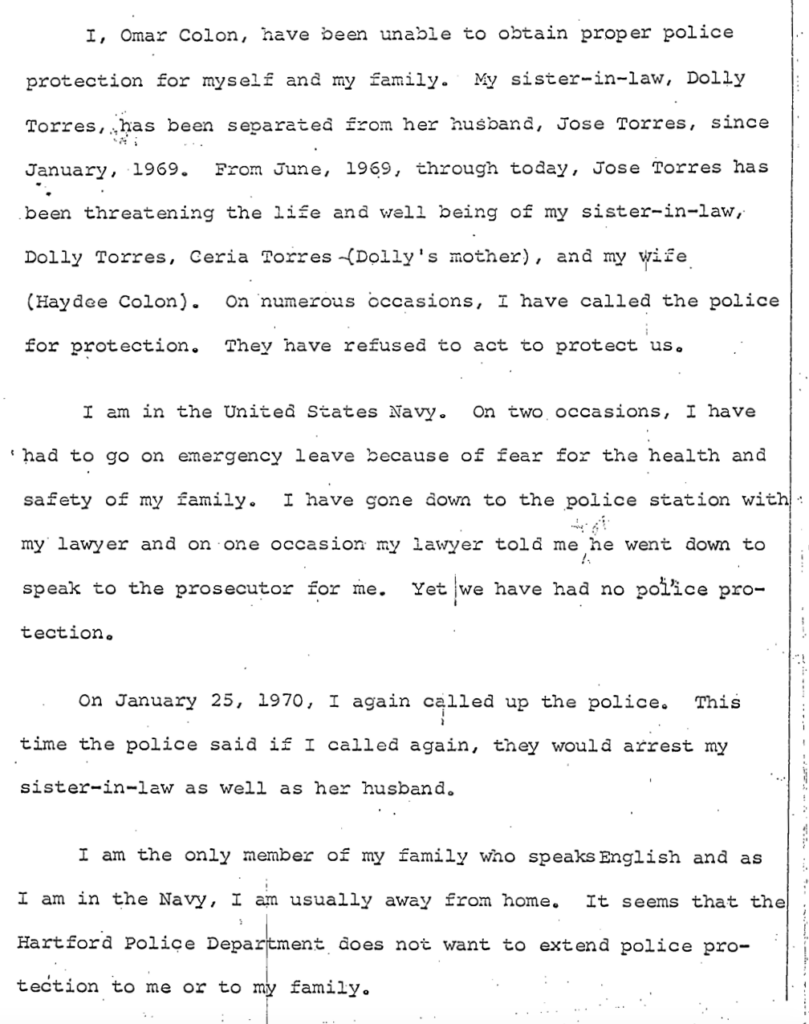

Other situations of police indifference to non-white crime victims in the Cintron archive can be considered under-policing, the counterpoint to the over-policing of poor Black and Brown communities that gets more attention and calls for reform. Two witness statements concern the same situation, in which the ex-partner of Marta “Dolly” Torres was threatening her and her family.

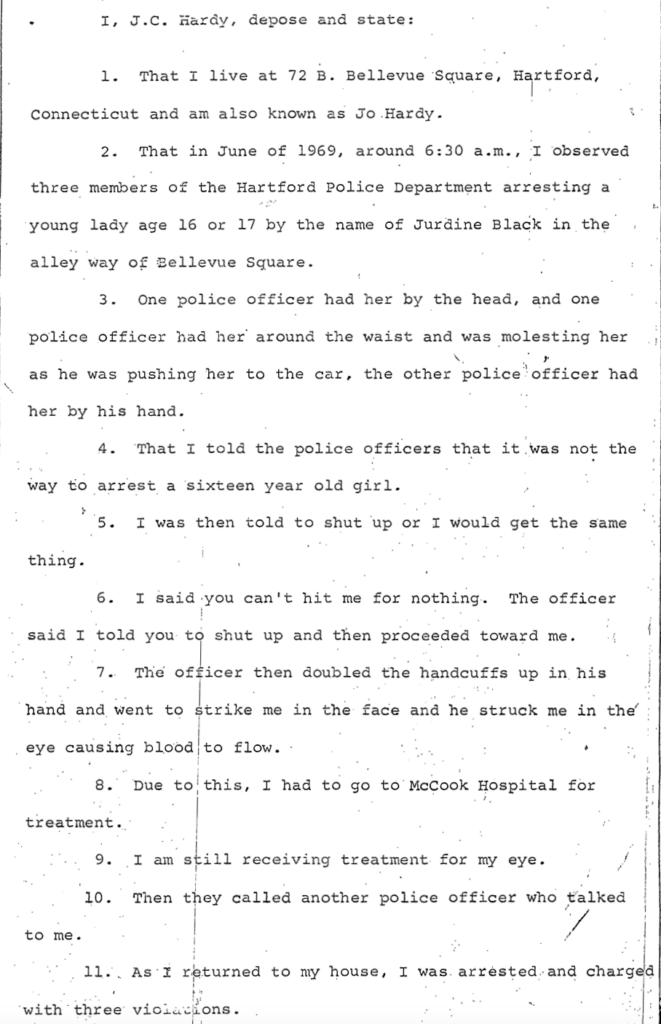

Beyond racialized under-policing, the HPD’s indifference towards the danger posed by Jose Torres represents a major pattern evident in the witness accounts: Lack of respect for women. The statement of J. C. Hardy reflects this.

The way Jurdine Black and Jo Hardy were treated at 6:30 am on that June morning is not aberrant; although presented as an example of police misconduct, the fact that this behavior was normalized within the HPD demonstrates its continuity with the project of policing. The Cintron witness statement archive contains this fundamental contradiction: its purpose is to reveal a problem and compel its fixing, while instead it reveals the system working as it was intended.

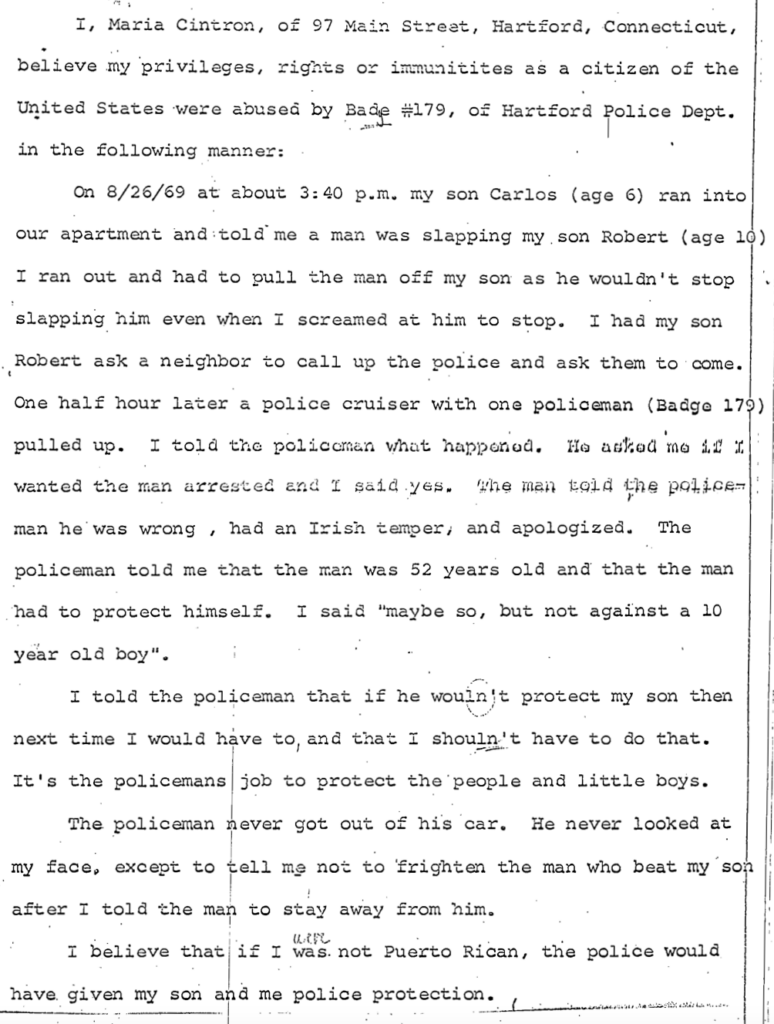

Maria Cintron provided the story that gave this case its name.

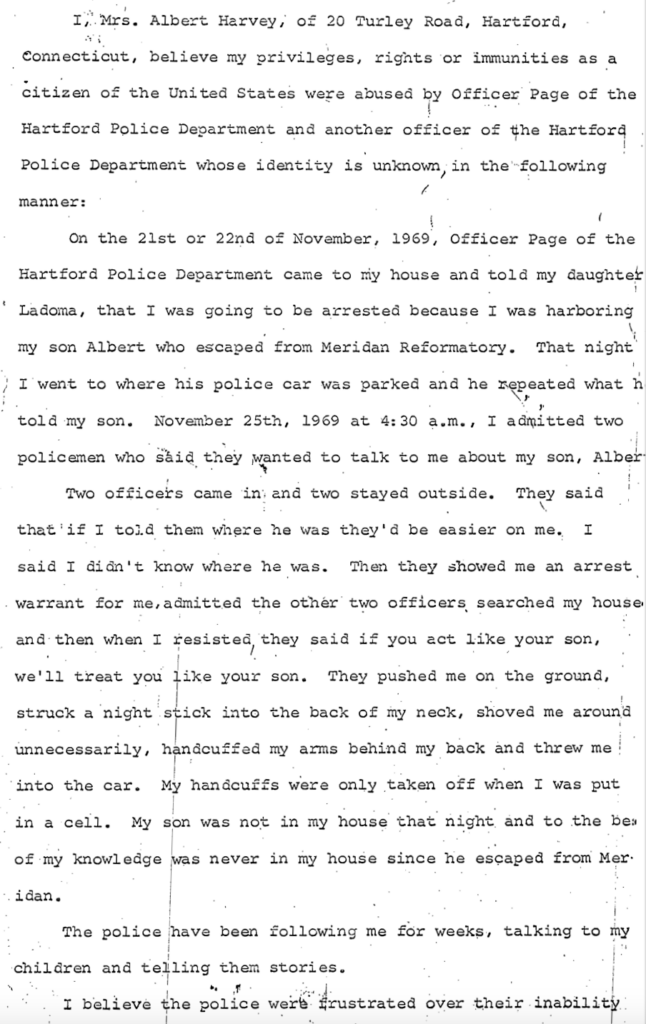

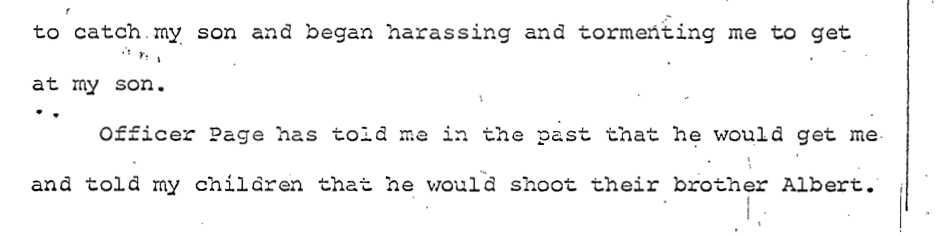

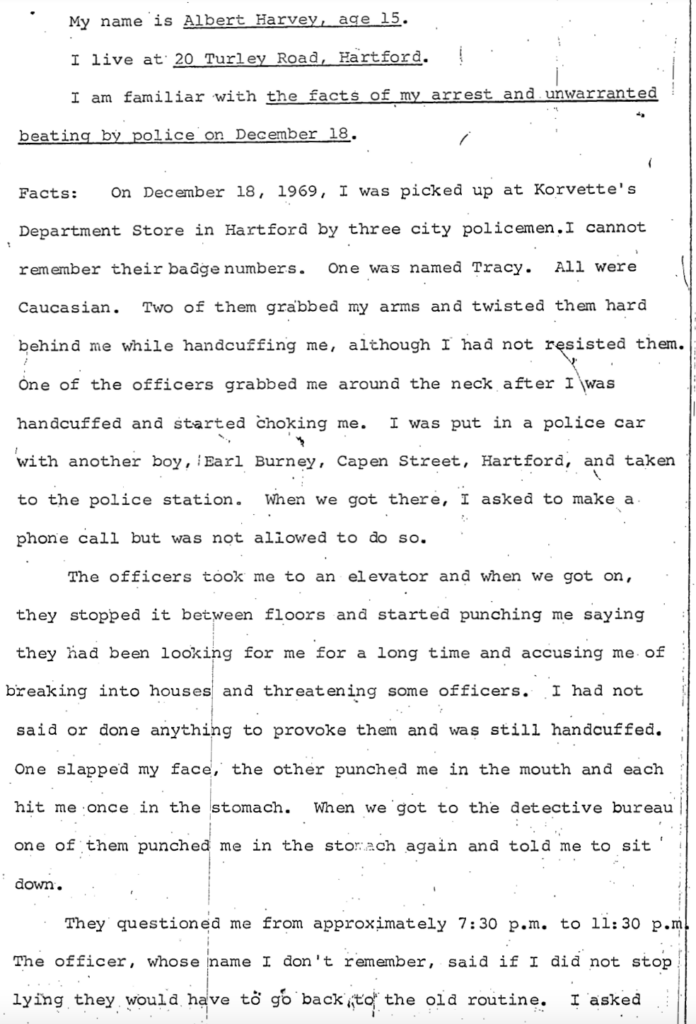

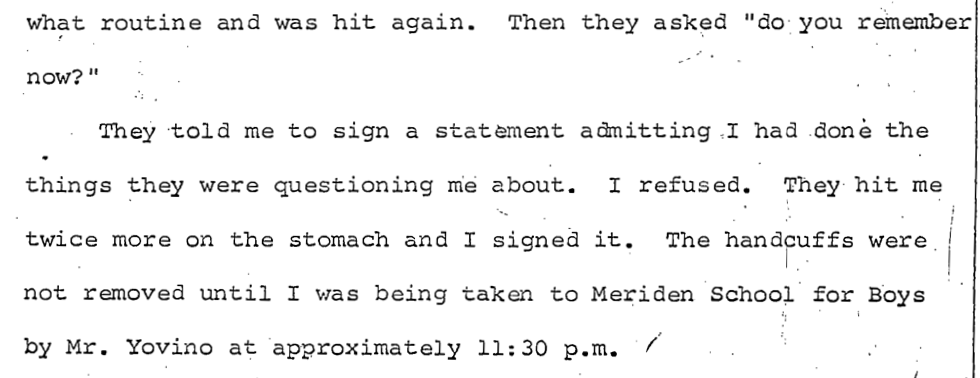

Throughout the Cintron archive, there are a range of disturbing stories in which HPD officers interfere in the relationships between Black and Puerto Rican parents and their children, specifically their sons. It can be tempting to find patterns where there is only coincidence, but even if we just consider each case alone, in the absence of pattern, intention, or premeditation, they are shocking enough. Jacqueline Harvey offered testimony about the abuse she suffered when HPD officers came looking for her fifteen year old son, Albert. Albert then offered his own testimony recounting what happened when he was found.

Throughout the Cintron archive, there are a range of disturbing stories in which HPD officers interfere in the relationships between Black and Puerto Rican parents and their children, specifically their sons. It can be tempting to find patterns where there is only coincidence, but even if we just consider each case alone, in the absence of pattern, intention, or premeditation, they are shocking enough. Jacqueline Harvey offered testimony about the abuse she suffered when HPD officers came looking for her fifteen year old son, Albert. Albert then offered his own testimony recounting what happened when he was found.

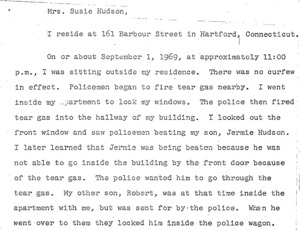

When interviewed by the Hartford Star in March of 1970, Jacqueline Harvey added that after the officers told her she was under arrest, she replied that she needed to go up the street to ask her sister to take care of her children while she was away. “They told me I was not going anywhere. So, I broke loose and ran toward my sister’s house,” after which Harvey was caught and subdued with force. The story is reminiscent of David Bristol’s, when he was targeted by police with a two year old under his care. Far from acting as a state proxy for parental protection (think of the prototypical image of the benevolent policeman holding a blond, blue-eyed child), this archive reveals the Hartford police getting in the way of such care and actively endangering children. Susie Hudson’s statement compounds the horror.

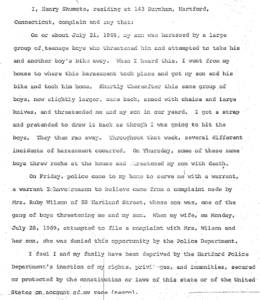

Another story, that of Henry Shumate, widens this thread of stories beyond mothers.

Shumate’s story raises another theme beyond police interference with Black and Puerto Rican family relations and active endangerment of children: the tight alliance between police and White people. Mrs. Ruby Wilson and her son are implied to be White, since Shumate explains that he believes the HPD’s behavior is a result of his race. The complement and logical end to the police neglecting or actively harming Black children is their loyal protection of White ones. In Shumate’s experience, this is a literal trade-off: One mother’s concern for her son must be valued at the expense of the other. In Maria Cintron’s story, the HPD officer who failed to protect Robert displayed more concern for the White attacker’s feelings than for his potential danger to other sons and other mothers. Robert, at ten years old, was over-labeled as a threat, while the White man was under-labeled as such; another sort of racial calculus in which the scales are balanced to a false zero, equilibrium always consisting of White safety and Black precarity.

Shumate’s story raises another theme beyond police interference with Black and Puerto Rican family relations and active endangerment of children: the tight alliance between police and White people. Mrs. Ruby Wilson and her son are implied to be White, since Shumate explains that he believes the HPD’s behavior is a result of his race. The complement and logical end to the police neglecting or actively harming Black children is their loyal protection of White ones. In Shumate’s experience, this is a literal trade-off: One mother’s concern for her son must be valued at the expense of the other. In Maria Cintron’s story, the HPD officer who failed to protect Robert displayed more concern for the White attacker’s feelings than for his potential danger to other sons and other mothers. Robert, at ten years old, was over-labeled as a threat, while the White man was under-labeled as such; another sort of racial calculus in which the scales are balanced to a false zero, equilibrium always consisting of White safety and Black precarity.

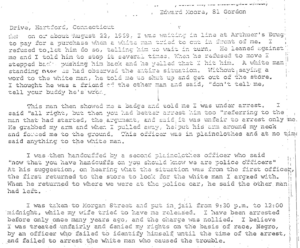

In other stories, this loyalty between the police (of any race) and Whites is articulated differently. Edward Moore provides an example.

Moore’s story is one of few included in the archive that take place entirely indoors, rather than the more ambiguous public space of the street. The space of the drugstore is orderly and well-lit and therefore sensitive to disturbance or aberration. It is easier for bystanders to witness police mistreatment here than on a dark street corner at night. To assume that this visibility entails respectful behavior is to misunderstand the nature of power, those that the police officer acts for. The drugstore visibility may have even encouraged the undercover officer to arrest Moore, conscious of the watchful eyes of fellow White customers and employees. Moore remarked specifically on the unspoken and assumed bond between police and Whites when he said, “tell your buddy he’s wrong.”

Moore’s story is one of few included in the archive that take place entirely indoors, rather than the more ambiguous public space of the street. The space of the drugstore is orderly and well-lit and therefore sensitive to disturbance or aberration. It is easier for bystanders to witness police mistreatment here than on a dark street corner at night. To assume that this visibility entails respectful behavior is to misunderstand the nature of power, those that the police officer acts for. The drugstore visibility may have even encouraged the undercover officer to arrest Moore, conscious of the watchful eyes of fellow White customers and employees. Moore remarked specifically on the unspoken and assumed bond between police and Whites when he said, “tell your buddy he’s wrong.”

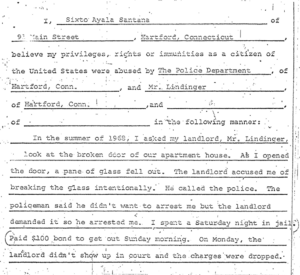

Finally, consider the story provided by Sixto Ayala Santana.

Finally, consider the story provided by Sixto Ayala Santana.

It is clear who the police work for; not the city government, nor the “public good,” but for White safety (which is, arguably, the “good public” referenced in the “public good”). Threats to White safety come in many forms and through many rich streams of the imagination. The reality of these threats is irrelevant to the force of police response, perhaps shown most extremely in the stories of HPD interference between and endangerment of mothers and sons.