Interactive Timeline

Hartford Consent Decree

This timeline follows the fifty-year lifespan of Cintron v. Vaughn, a consent decree which placed the Hartford Police Department (HPD) under judicial oversight from 1973 to 2023. The case began as a class action lawsuit brought in 1969 against members of the HPD and city government by community organizations as well as Black and Puerto Rican citizens who had experienced police abuse. Cintron may be the first and longest-running consent decree entered into by a U.S. police department, and yet it is relatively unknown in discourses surrounding police reform.

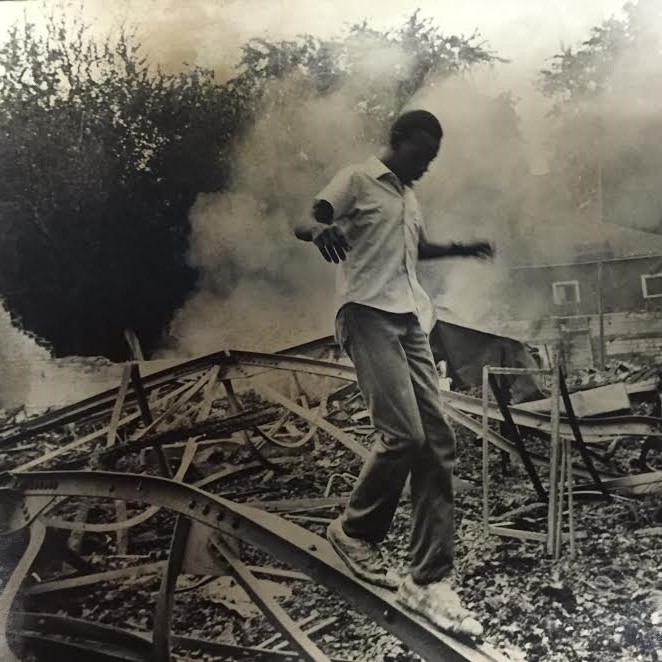

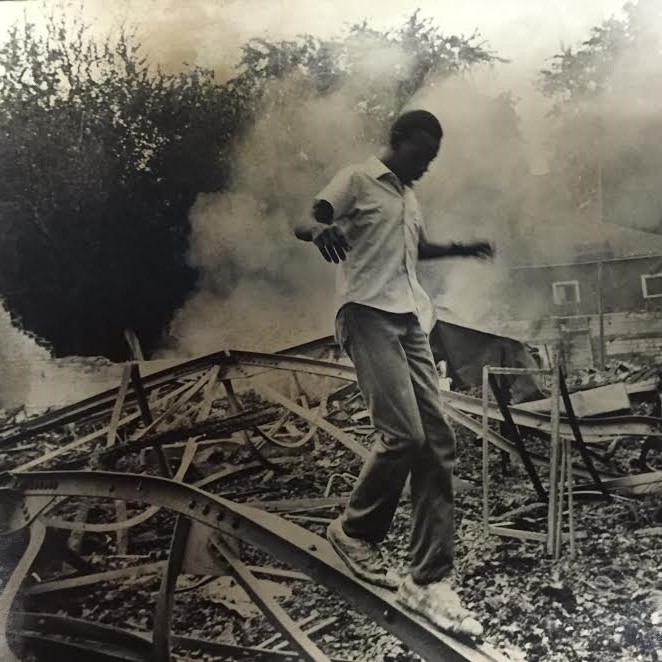

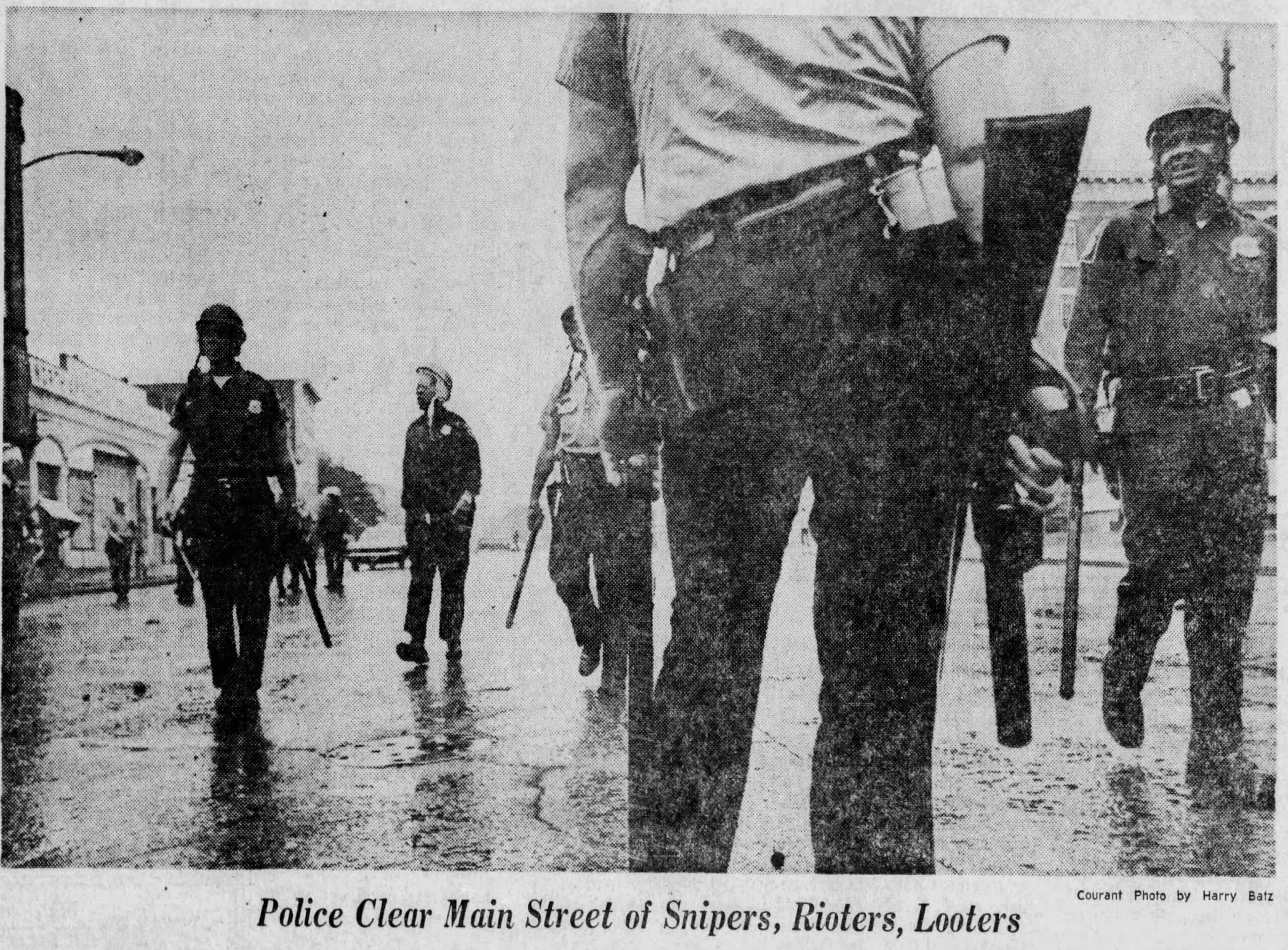

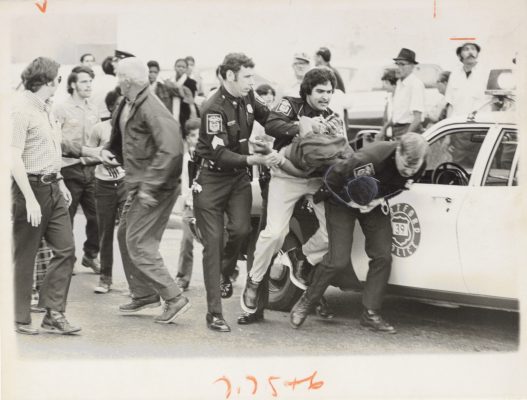

Introduction: 1960s

The period of the 1960s has come to be defined by powerful social uprisings against the systemic racial discrimination perpetuated by de facto segregation in educational, legal and social systems. Entirely intertwined with these spheres of violence is the use of excessive force as a weapon of control by law enforcement agencies, as a means to physically uphold these systems of racial discrimination. As December 1969 closes out the decade, members of the Black and Puerto Rican community in Hartford, Connecticut file a class action lawsuit against the Hartford Police Department for subjecting them to unconstitutional and senseless violence. This class action lawsuit would come to be known as Cintron v. Vaughn.

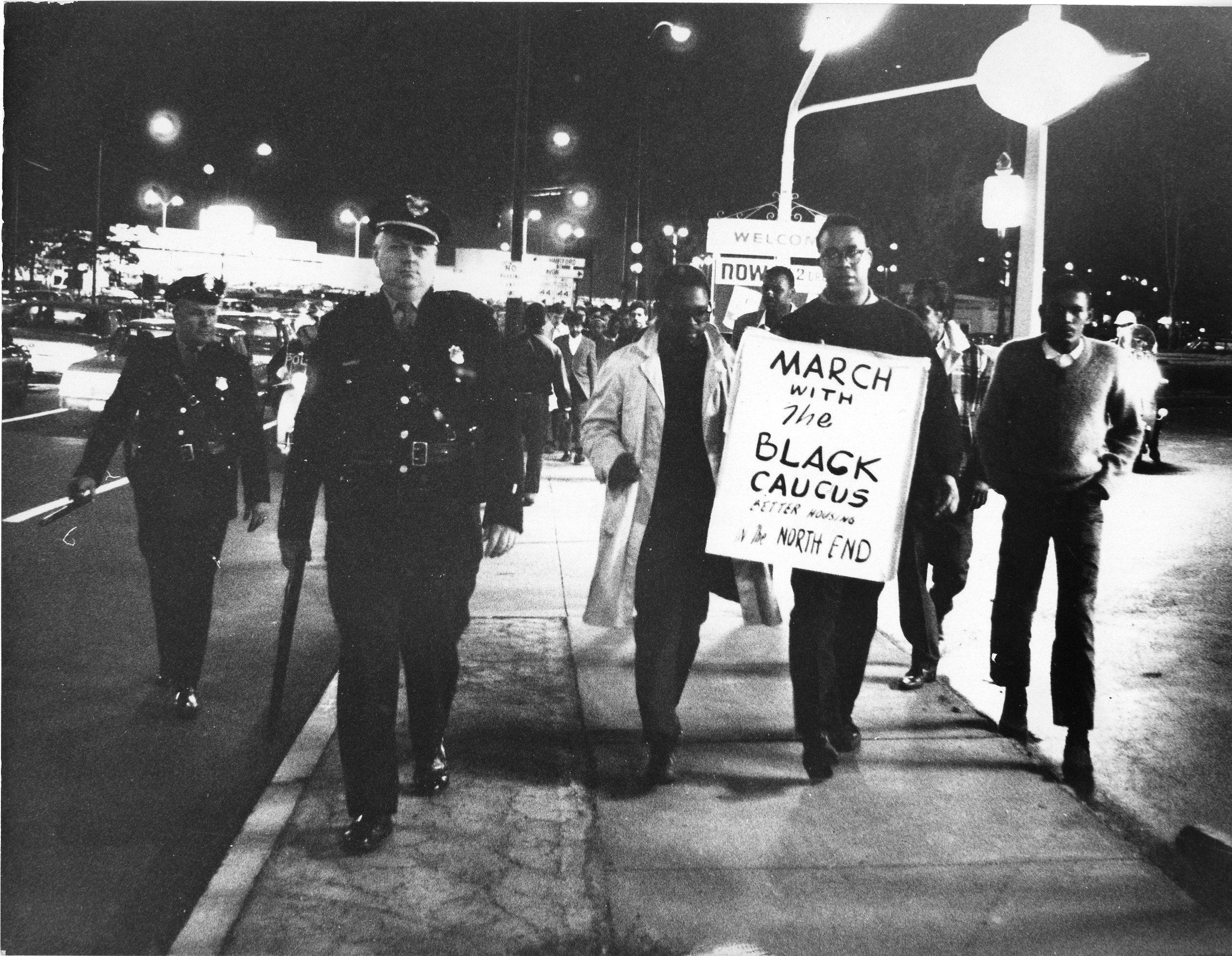

1969

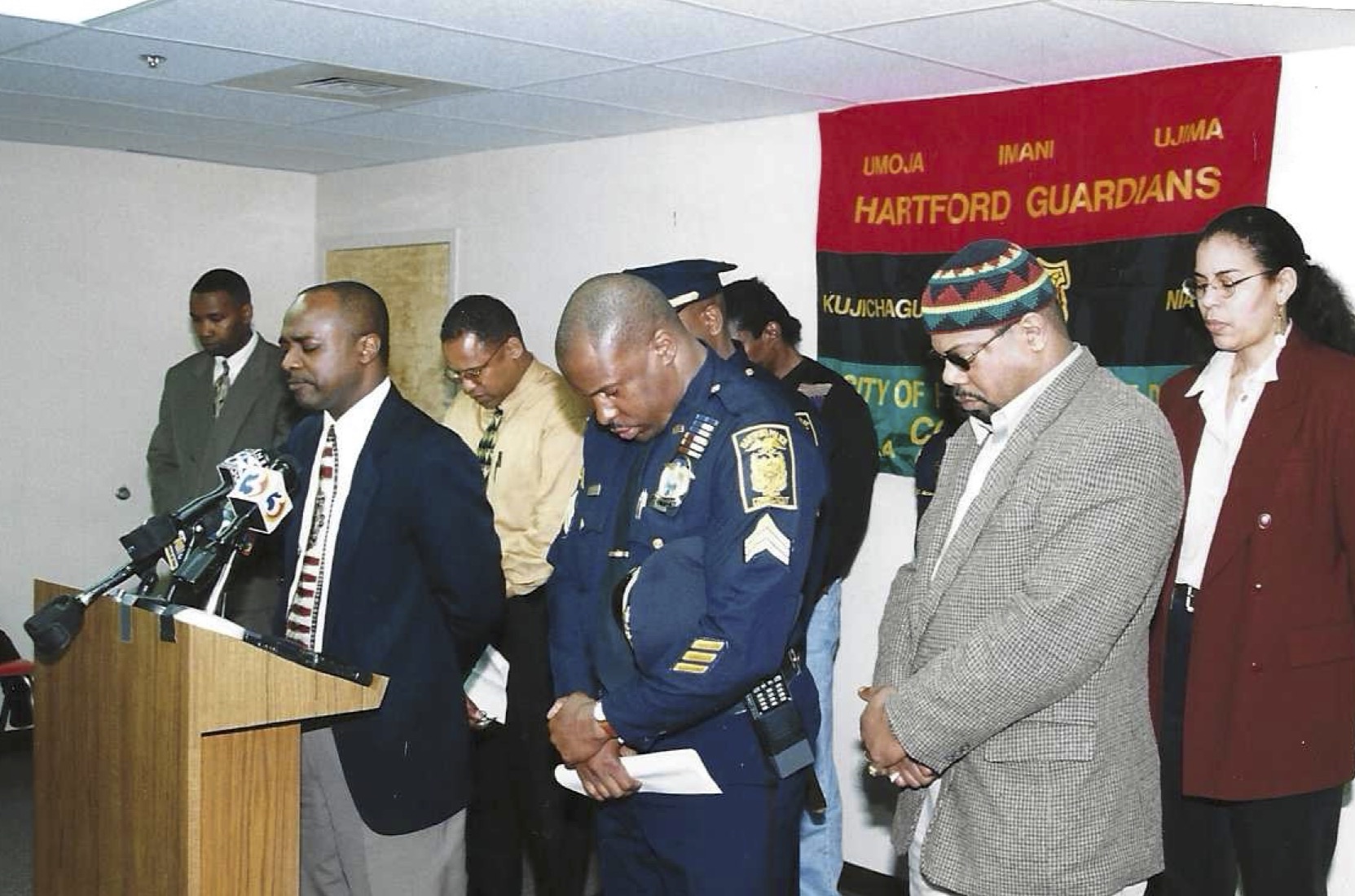

In response to a series of fatal police shootings and subsequent public outcry, the Guardians—a fraternal organization of Black Hartford Police officers—perform a walkout to call attention to their grievances regarding a culture of discrimination within the police force. Their actions reaffirm the conditions that compelled Black and Puerto Rican organizers to file a class action lawsuit against the HPD and city government, Cintron v. Vaughn, alleging a pattern of race-based abuse.

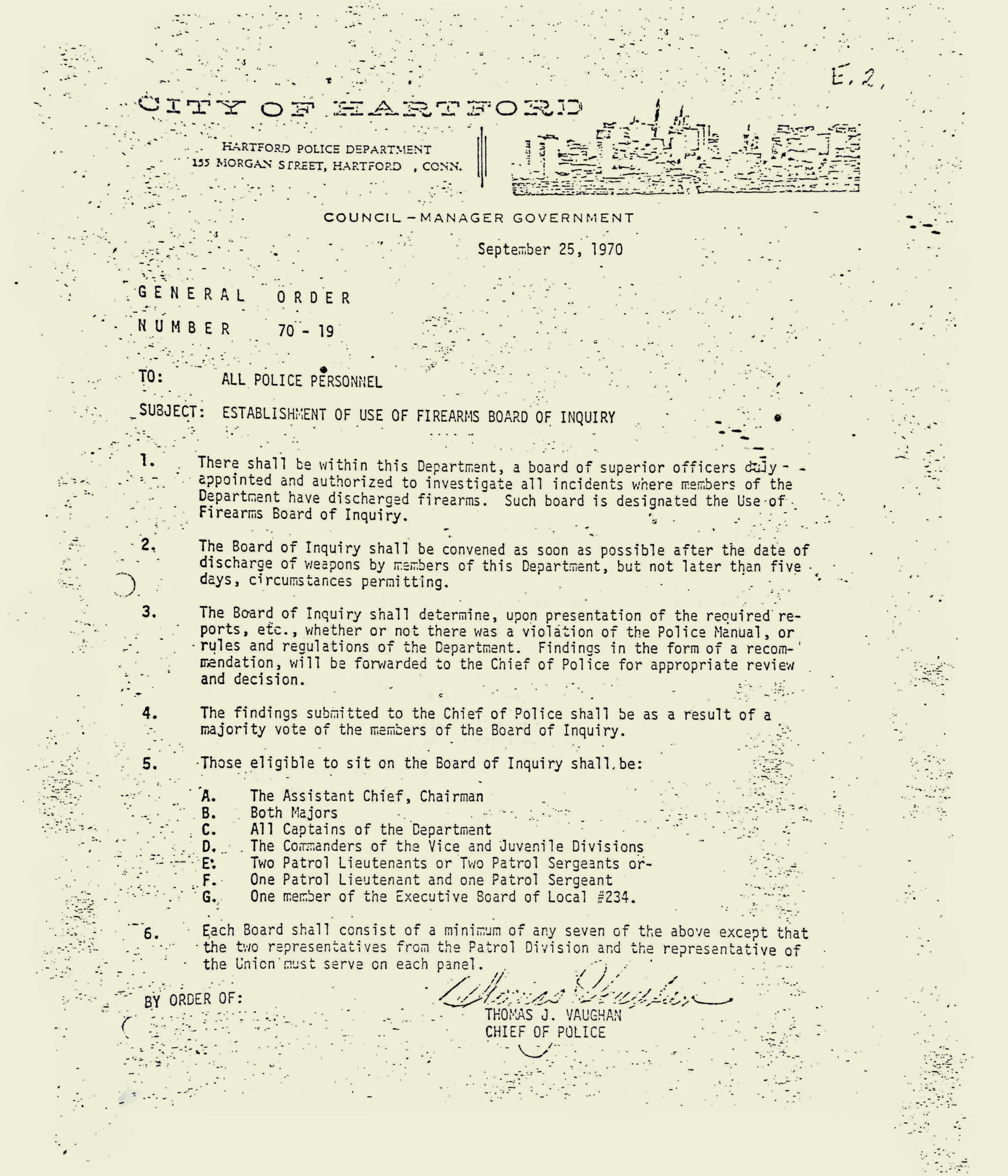

1970

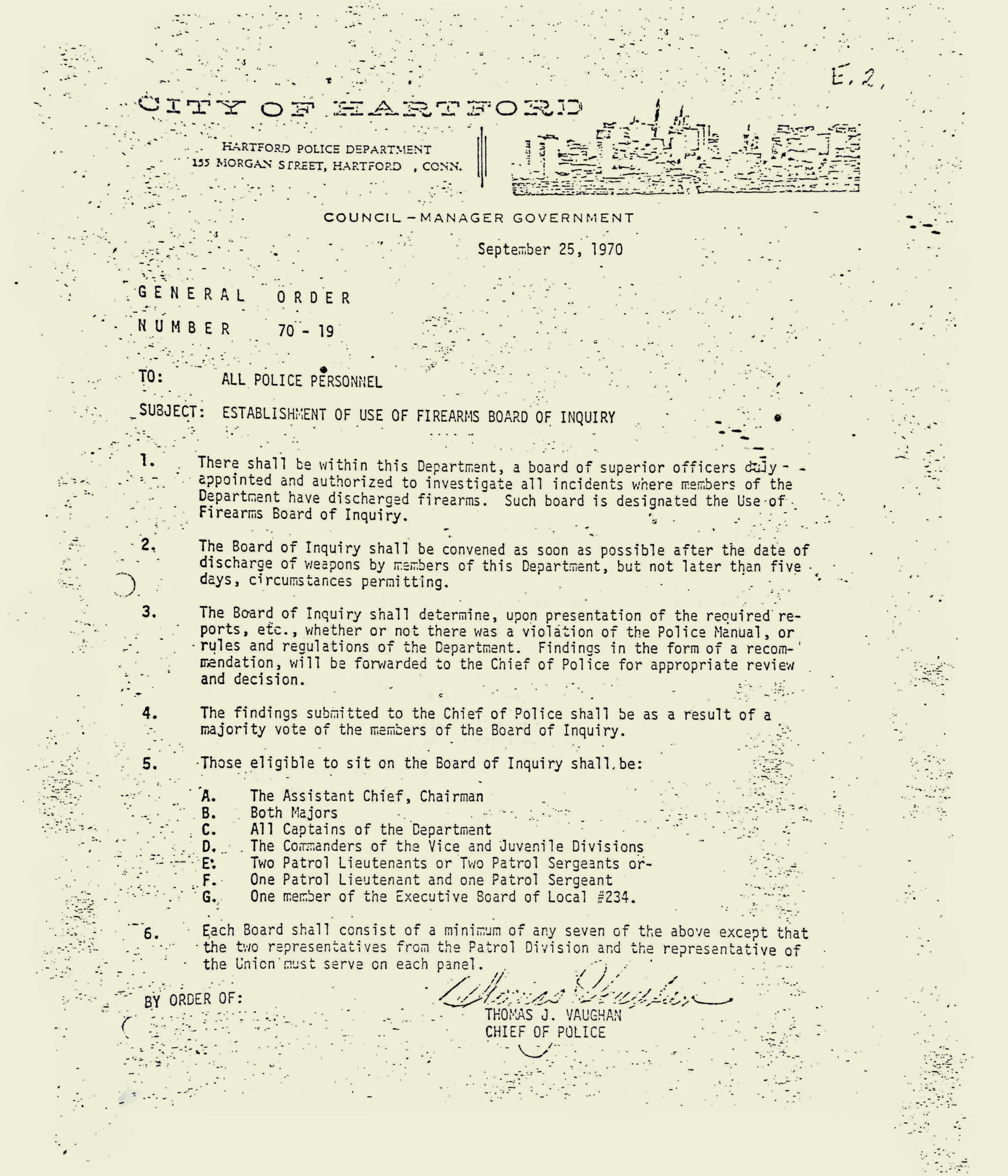

US District Judge M. Joseph Blumenfeld denies the city’s motion to dismiss Cintron v. Vaughn. Hartford’s community organizers are outraged after several more young Black and Latino men die at the hands of police. A city council committee is convened to investigate police use of force, but they decide to not recommend any change in guidelines.

1973

Judge Blumenfeld resolves Cintron v. Vaughn in a consent decree between the HPD and Black and Puerto Rican community groups mediated under judicial oversight. Reactions to this decision vary, as many community members believe that the decision does not hold the HPD fully accountable for their harmful practices. This agreement establishes a precedent, constituting likely the longest-held consent judgment with a U.S. police department, a practice that continues through the present day.

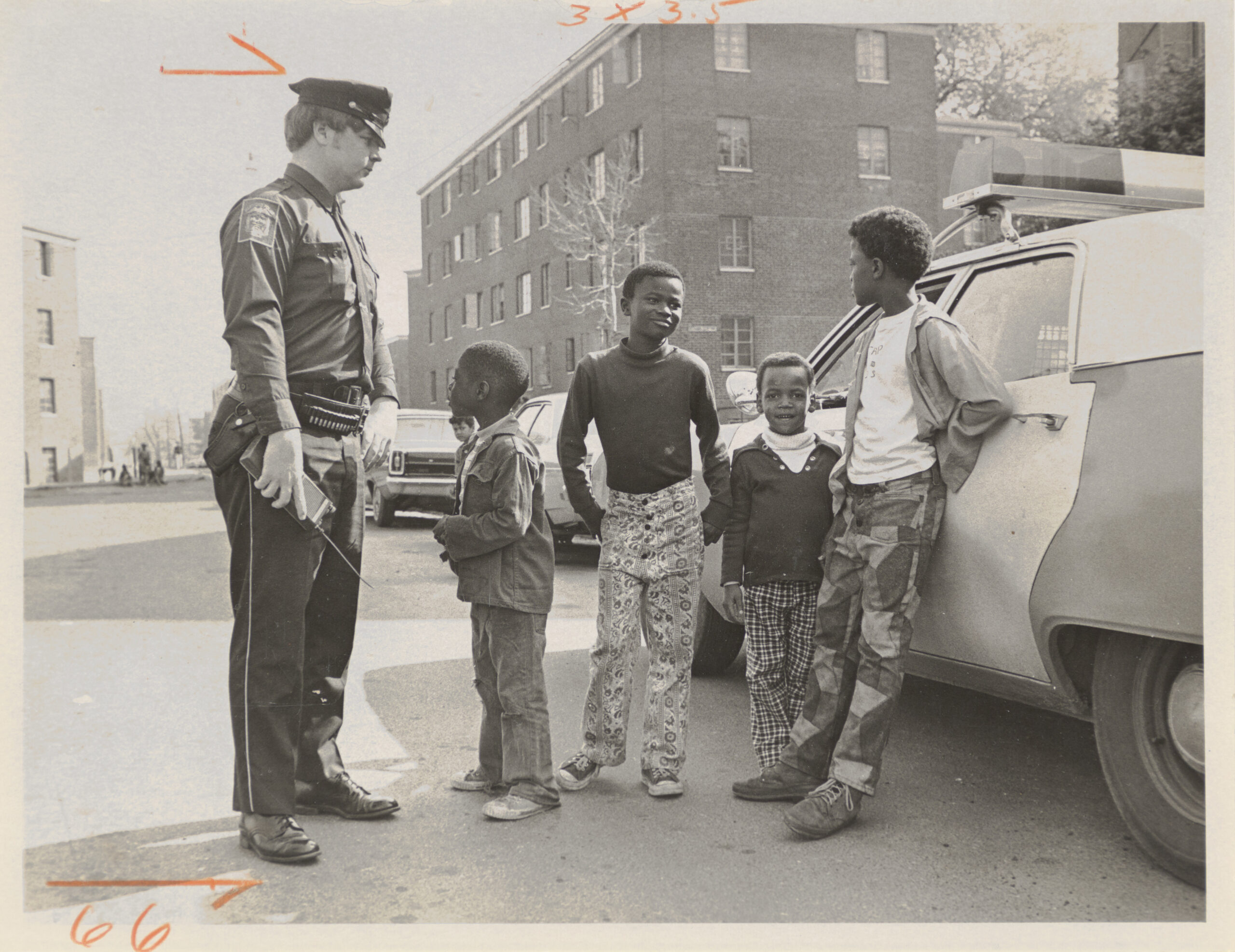

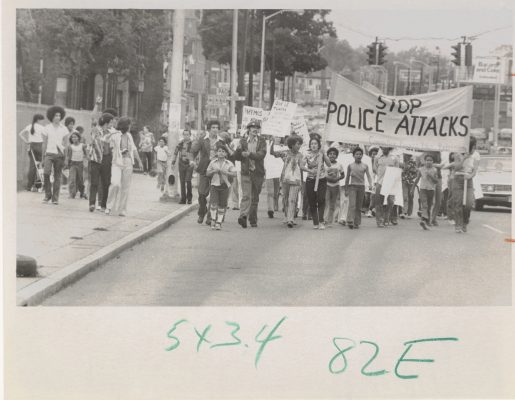

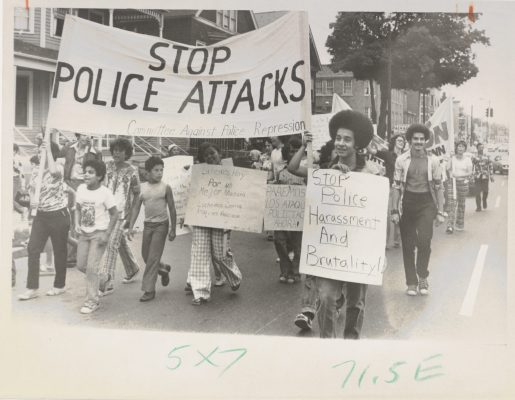

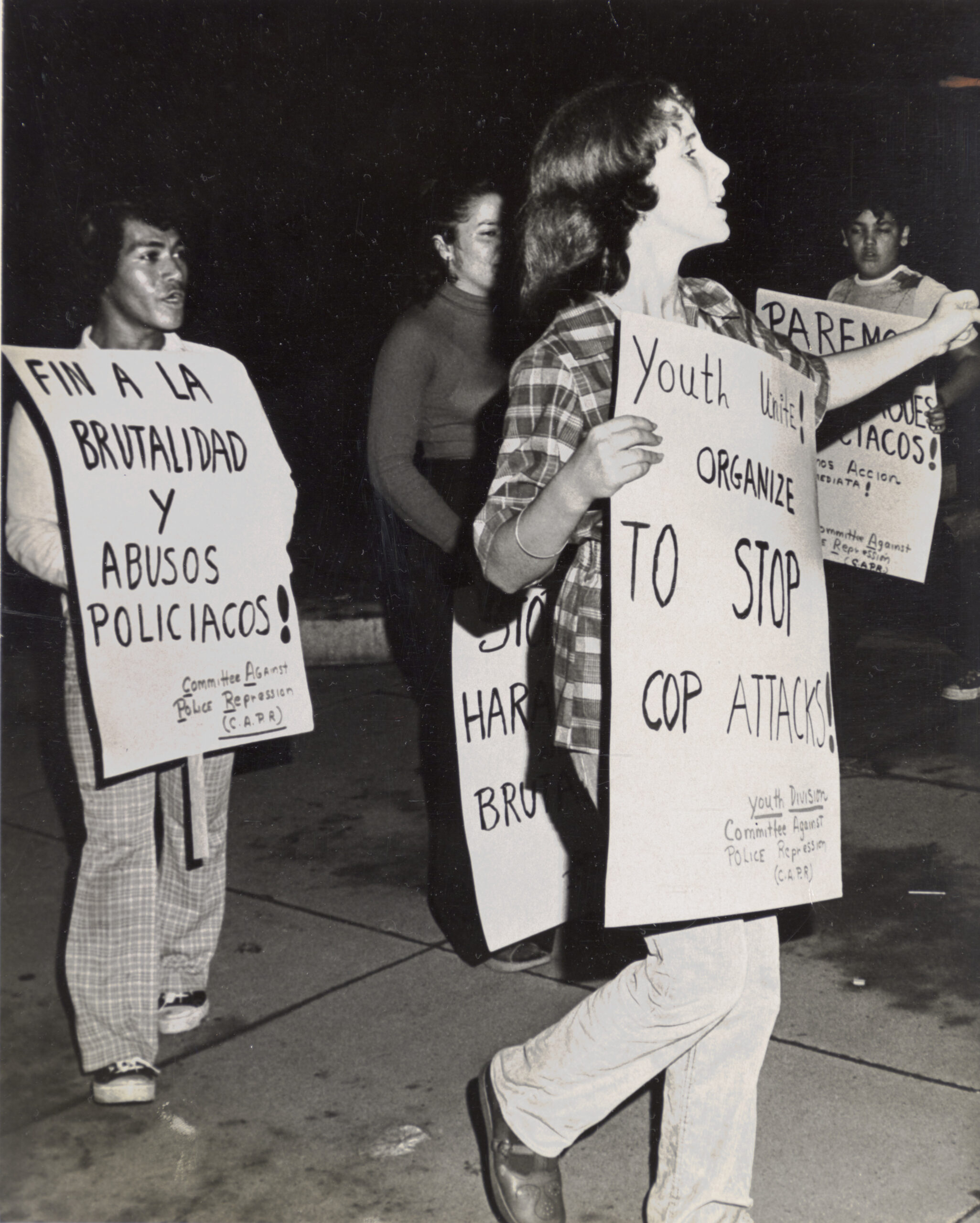

1976

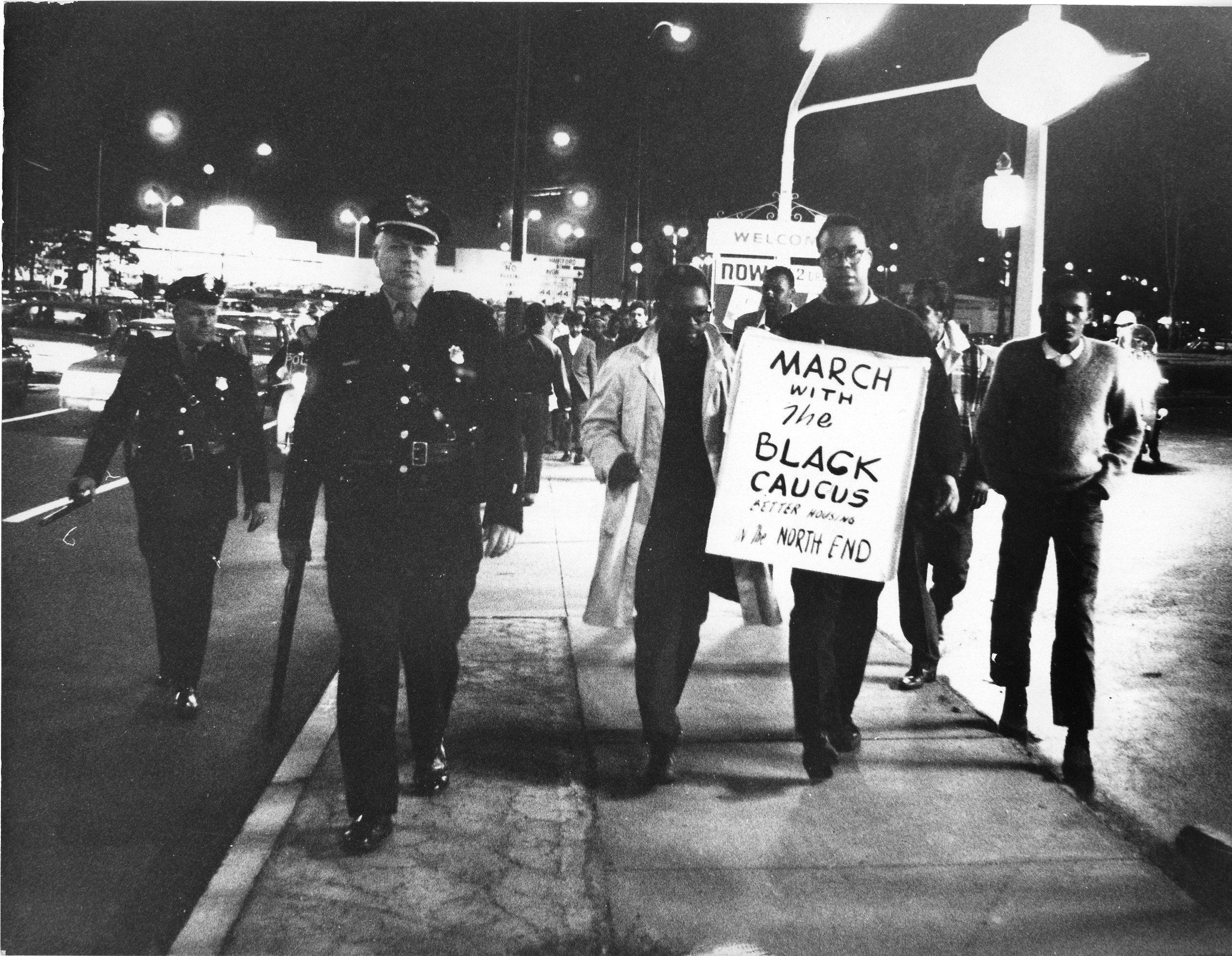

No further action is taken within the consent decree, but Hartford community organizers continue to push for change through direct means. The Committee Against Police Repression (CAPR) organizes a protest in language that mirrors Cintron; they march against “a pattern of harassment and brutality” by the HPD, specifically claiming that officers have been arresting scores of Puerto Rican youth for simply walking down Park Street in the North End. Representatives of CAPR succeed in getting a meeting with police officials, who promise to investigate complaints of arbitrary arrest and rough treatment in the area.

1977

Hartford Police are accused of violating the 1973 agreement during a fight between two HPD officers and two Puerto Rican brothers. The fight took place outside a bar on Park Street, where the brothers claim that one of the policemen threw the contents of a paper cup at them, instigating a fight. Neither party ends up arrested, however the Puerto Rican brothers claim that the police officers broke the law and should be held accountable. The Puerto Rican community felt “very strong about the decision not to seek warrants against the policeman,” speaking to the need for an independent police-civilian review board to take civilian complaints seriously.

1980

From 1977 to 1980, calls for a civilian review board circulate among activist and community groups in Hartford. In February, the Hartford City Council votes to “take steps towards formation of a civilian review board to investigate complaints of brutality against the city’s Police Department.” This City Council vote and presumed advancement towards adopting a new form of accountability stirs up disagreement within the HPD, as Chief Hugo J. Masini stands firmly against its implementation.

1981

A group of Black HPD officers file a motion on the basis of Cintron, alleging discriminatory promotion practices. Previously in 1979, the Guardians had filed a set of complaints with the chief concerning these same issues, which were not adequately addressed. They ask for an injunction preventing all promotions until the problem is solved. Nothing came of this spate of litigation, and the motion would later be withdrawn in 1985.

1982

In January, the City Council renews discussion about establishing a civilian review board, which had been debated several years prior, bringing the issue to a vote. This proposed board, however, looks very different from the initial plan that the Human Relations Commission (HRC) recommended in the wake of the Guy Brown shooting.

1990

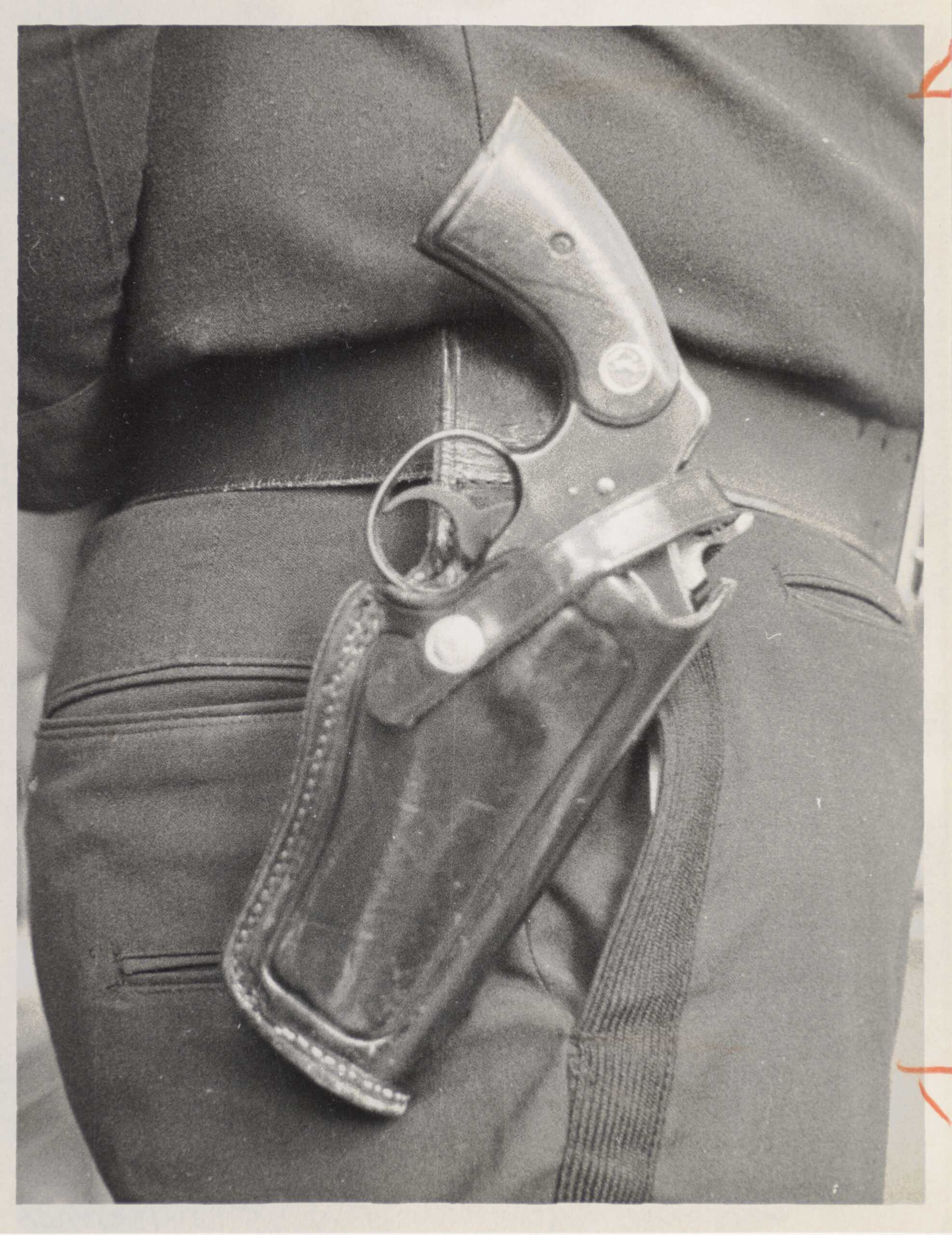

Following another gap in case activity, the defendants succeed in changing the terms of the consent decree such that officers can carry their semi-automatic service weapons while off duty.

1991

The HPD comes under scrutiny after Officer Ezequiel Laureano is caught on film striking a handcuffed student during a riot at the University of Hartford. The incident occurs the very same day that Rodney King is filmed being beaten by the LAPD. Laureano is arrested for assault, and the case causes a public scandal which brings attention to the HPD’s weak structure of accountability. The Hartford Courant publishes a thorough report on the department’s shortfalls and lack of effective deterrents against police use of force, which pressures the department to institute several policy changes.

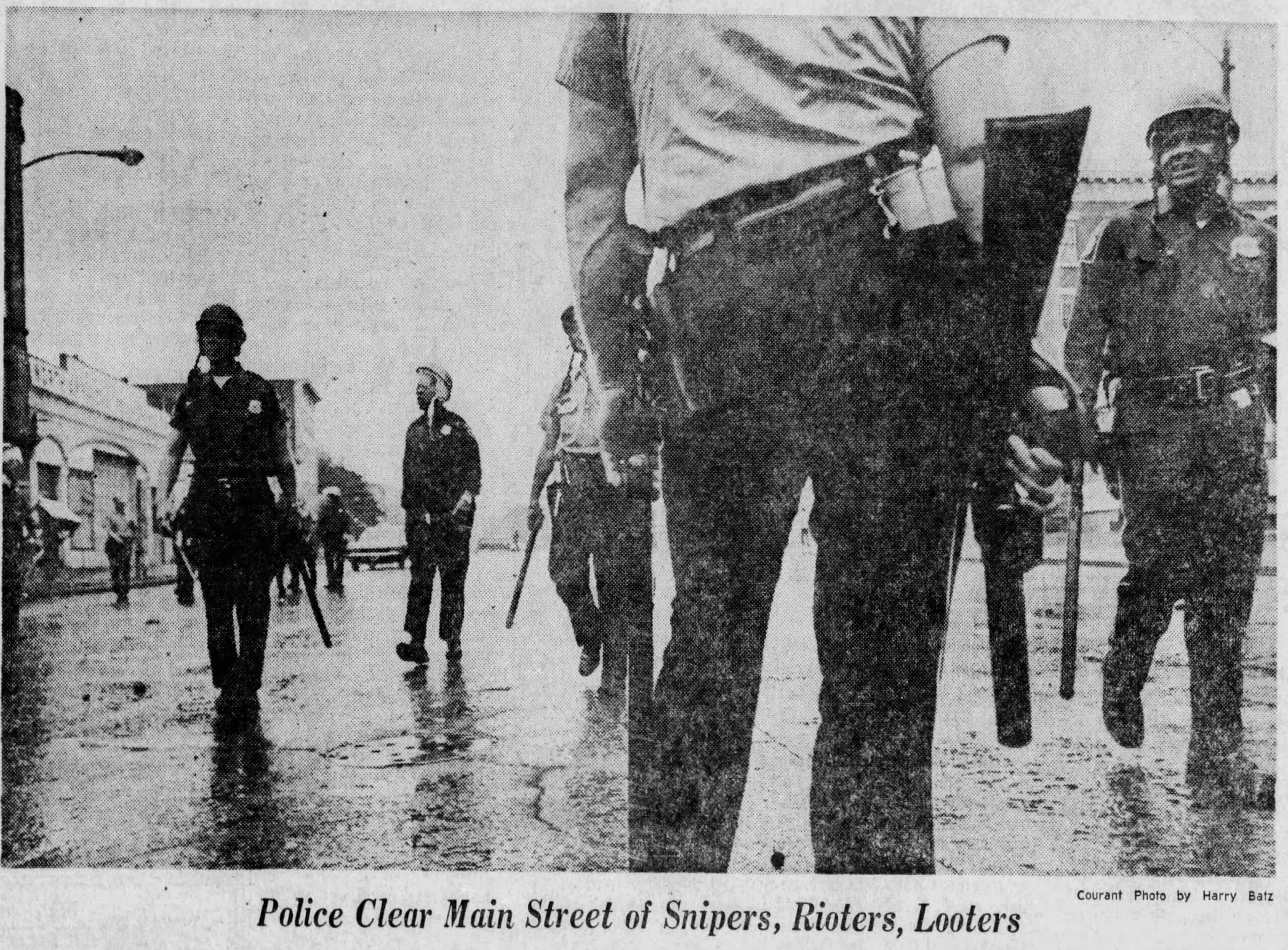

1992

Tensions rise between the HPD and the city administration. Officers feel that the city is targeting them for political gain, swept up in a national wave of anti-police sentiment ignited by the beating of Rodney King and subsequent LA riots. Mayor Perry’s promise that Hartford “is not Los Angeles” stands in tension with the city’s history of political organizers who have poked holes in the myth of the North’s freedom from racial inequality.

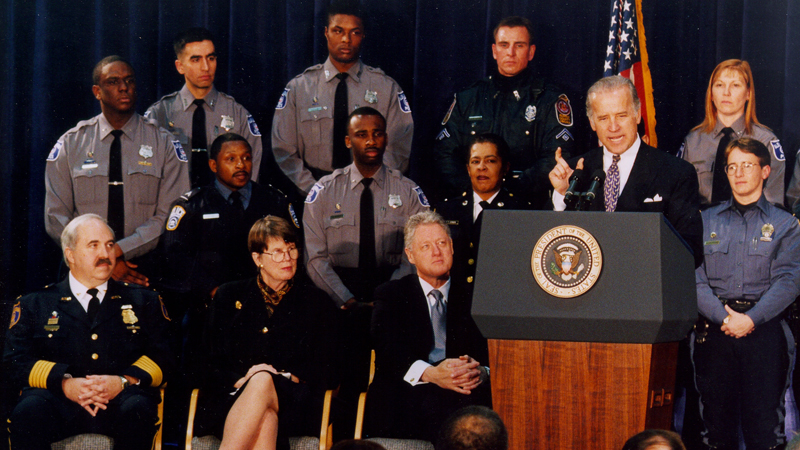

1994

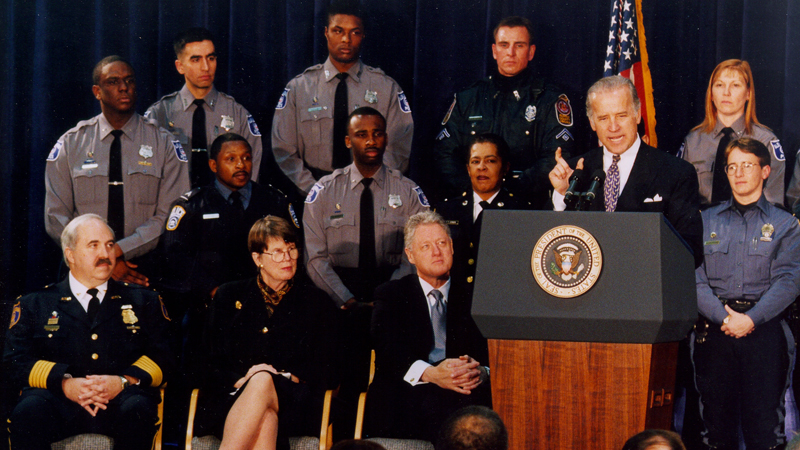

The 1994 Crime Bill sets judicial precedent for the implementation of consent decrees against police departments, specifically through Section 14141 regarding the jurisdiction of the Department of Justice in evaluating a police department’s violation of citizenship. Cintron is of particular interest for this very reason, as it takes place twenty years prior to this perceived authorization, and seems to be left out of the historical memory that centers 1994 as the inception of this practice.

1997

In June 1997, claims of discriminatory conduct are brought against Deputy Chief Robert Casati by a colleague, Sergeant Daryl Roberts.

1998

In January, an internal police hearing is convened to investigate Casati’s mis/conduct; behavior that was previously regarded as standard policing, and will continue to be regarded as such behind closed doors. There is public pressure on both Casati and Chief Croughwell to resign over the handling of the case. The HPD comes under more fire when two sex workers claim a group of officers had been continuously abusing them for over two years.

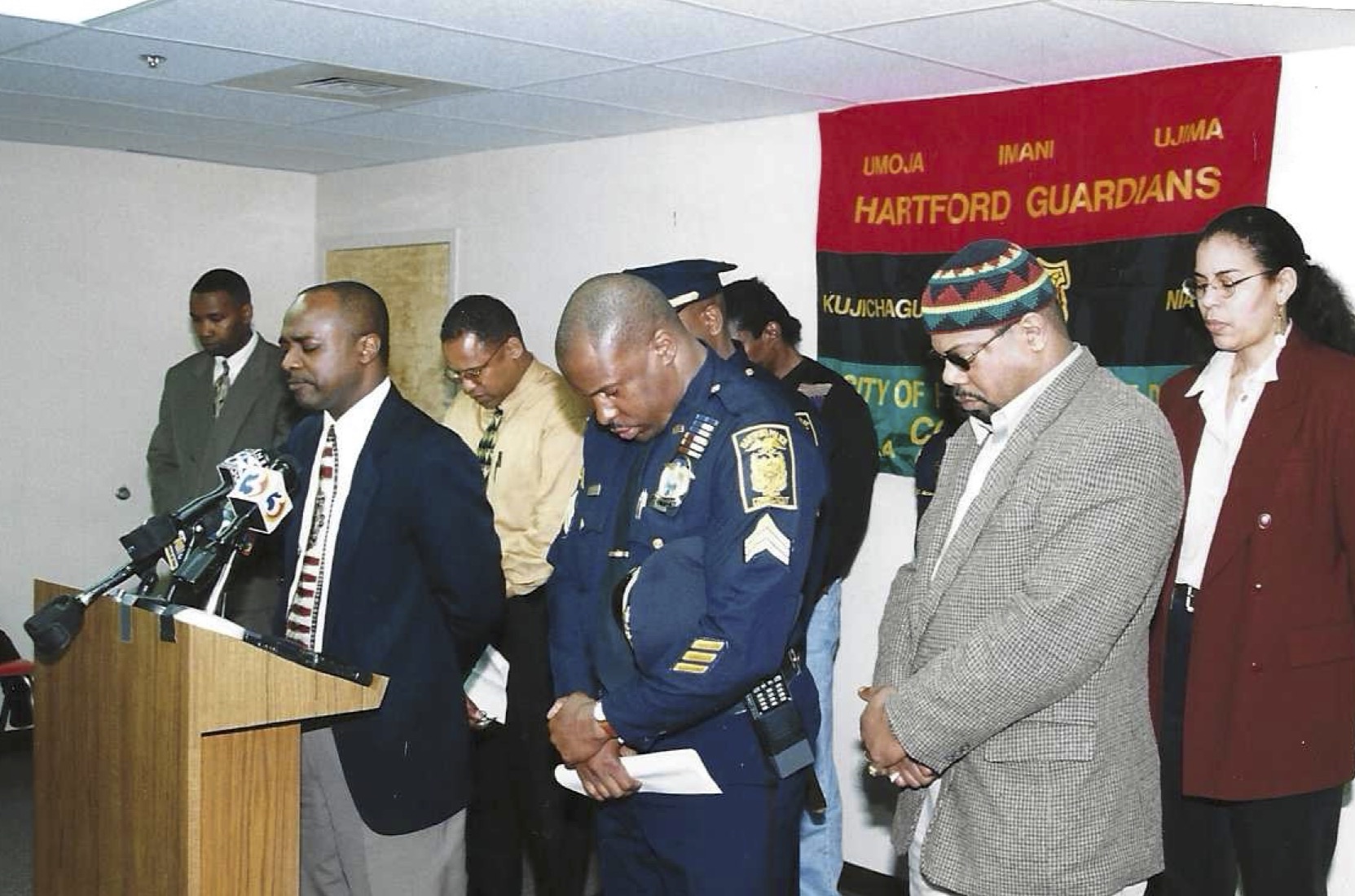

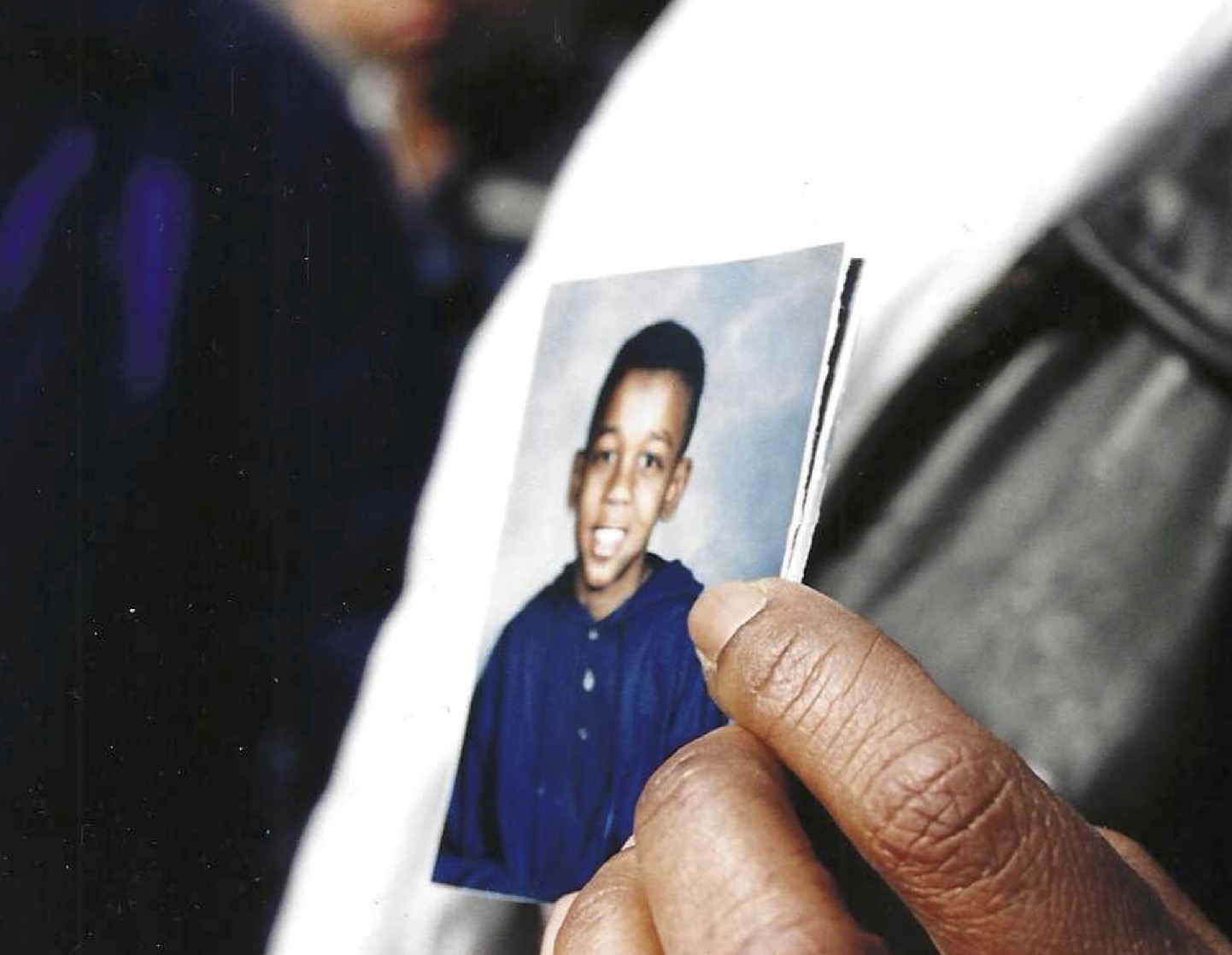

1999

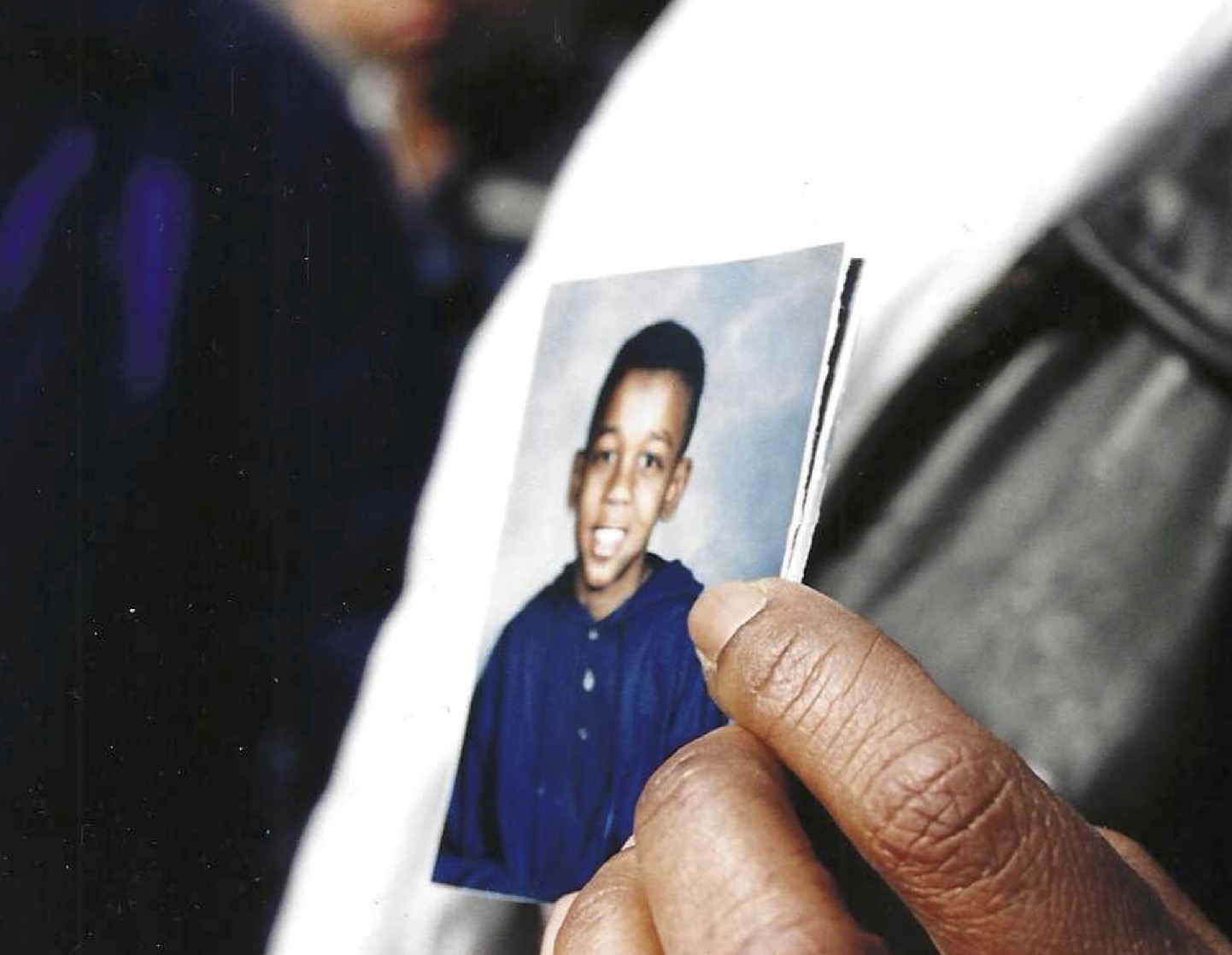

HPD Officer Robert Allan fatally shoots fourteen-year-old Aquan Salmon on April 13. The collective grief and outrage following this tragedy unifies local activists, prompting calls to revisit the 26-year-old consent decree as an avenue for police accountability.

2000

Salmon’s killing in 1999 brought out deep seated anger around Hartford regarding the HPD’s targeting of Black and Latino civilians and the failure to protect those they serve. As the millennium turns, protests across the city give voice to these feelings and community organizers continue to work toward “Justice for Aquan.” Attorney Richard Bieder is enlisted to oversee Cintron’s litigation as Special Master. He finds Officer Allan’s use of force justified, if tragic. In May, Robert Casati’s discriminatory remarks are defended by Arbitrator Albert G. Murphy in his move to reinstate Casati to his position as Deputy Chief. Acting Police Chief Deborah Barrows is ousted in July after frustrations surrounding her inability to adequately investigate the Salmon shooting boil over.

2001

In October, Judge Marshall K. Berger grants the city’s application to vacate Arbitrator Murphy’s decision excusing Casati’s behavior. Judge Berger finds Casati’s reinstatement to be a violation of public policy and in “excess of the arbitrator’s authority under the submission.”

2003

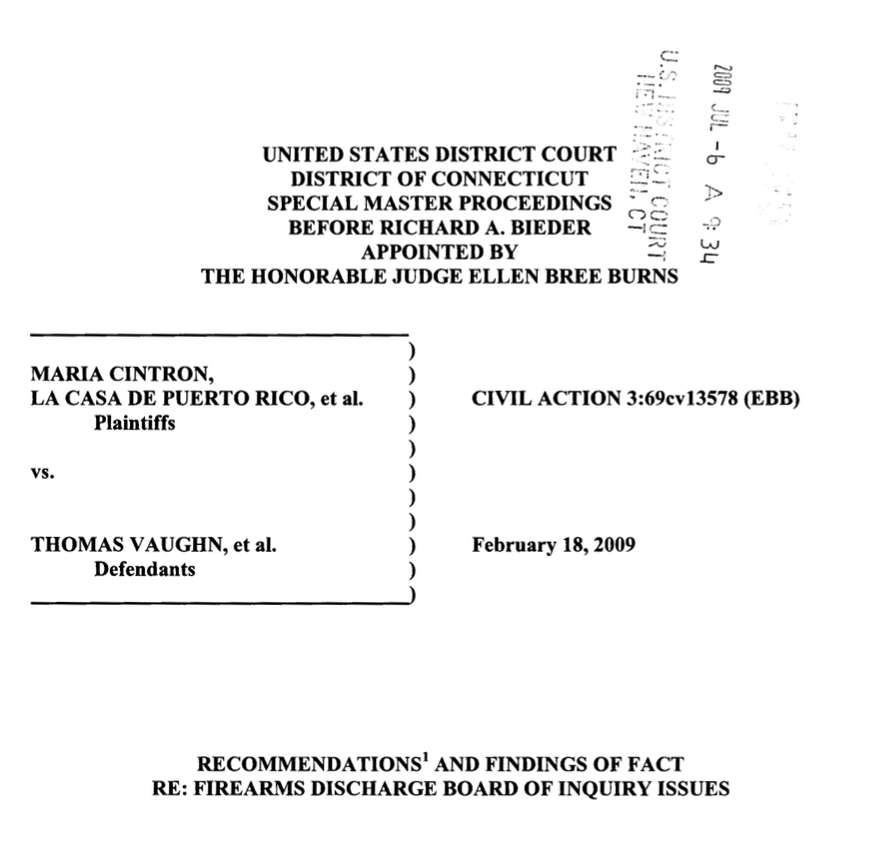

The parties come to an agreement on updated Firearms Discharge Board of Inquiry (FDBI) guidelines, the demands of which were initiated in 1999 in response to Salmon’s shooting. HPD Officer Robert Murtha shoots an unarmed citizen, Elvin Gonzalez, and the incident’s investigation is obstructed by union members.

2004

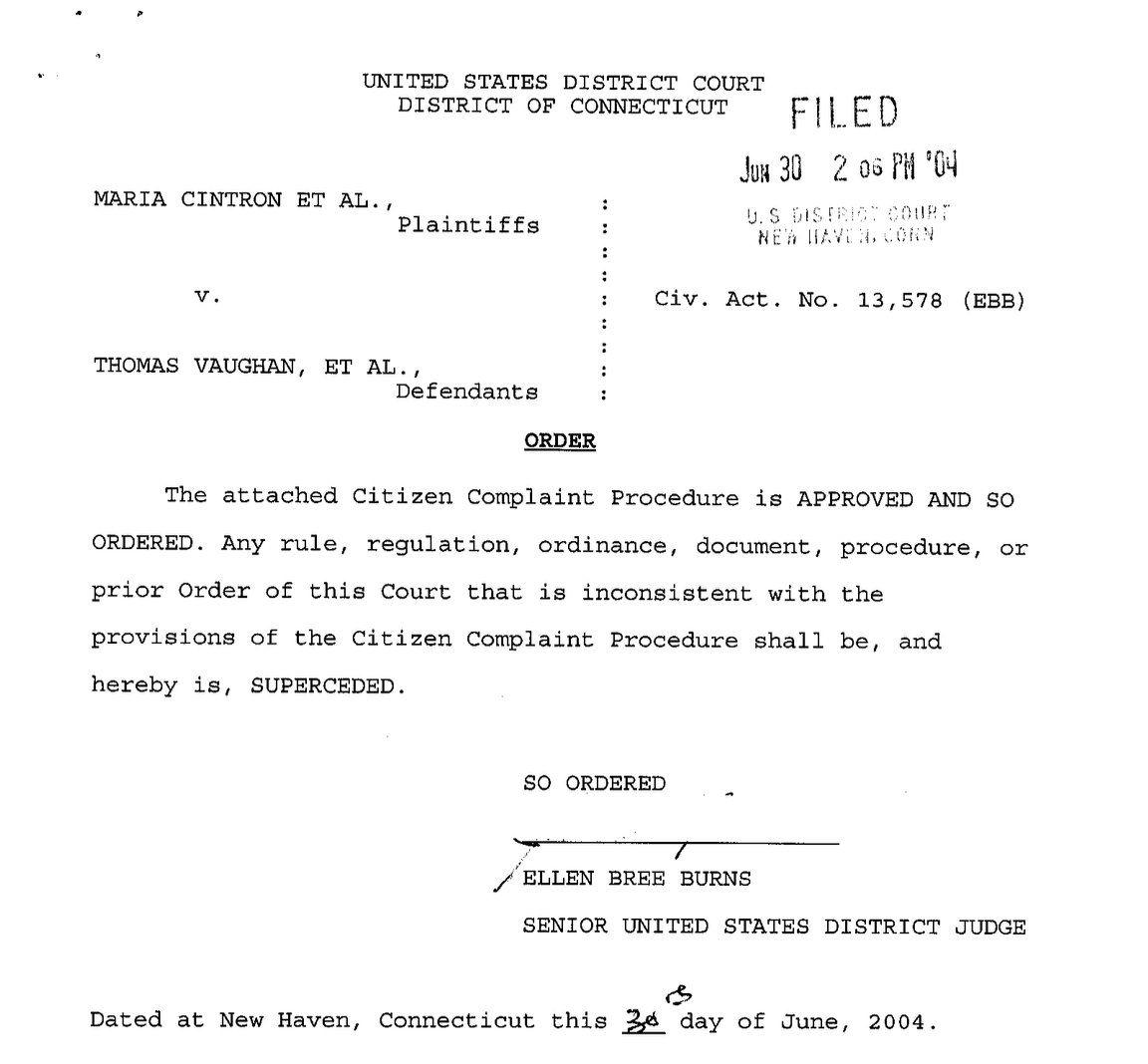

The Cintron parties agree on a new civilian complaint procedure, known as the “2004 Order.” Plaintiffs file two motions for contempt, one of which charges noncompliance with the 2004 Order.

2005

The Plaintiffs re-file a motion for contempt alleging that the HPD has not followed the 2004 Order, and another regarding their failure to devise an affirmative action plan to increase racial diversity on the force.

2007

Following an extensive investigation, Special Master Bieder files a report finding the HPD in violation of five provisions of the 2004 Order. Judge Burns agrees with three of these, and affirms Bieder’s suggested sanctions, including a required public relations campaign to inform citizens about the complaint procedure.

2009

Special Master Bieder submits his second report concerning FDBI issues, specifically the investigations of three shootings that occurred from 2003-2004 including Murtha’s. Judge Burns approves Bieder’s contempt findings on several counts. Sanctions consist of a requirement for updated guidelines and training to fix said issues.

2010

Both Cintron parties enter into a new settlement agreement, generally referred to as the “2010 Agreement,” requiring the defendants to revise several procedural protocols. The settlement stipulates that both parties agree to resolve future disputes outside of legal intervention, to the best of their abilities.

2016

Hartford City Council passes a resolution requesting the court not sunset the consent decree until the HPD solves several internal issues.

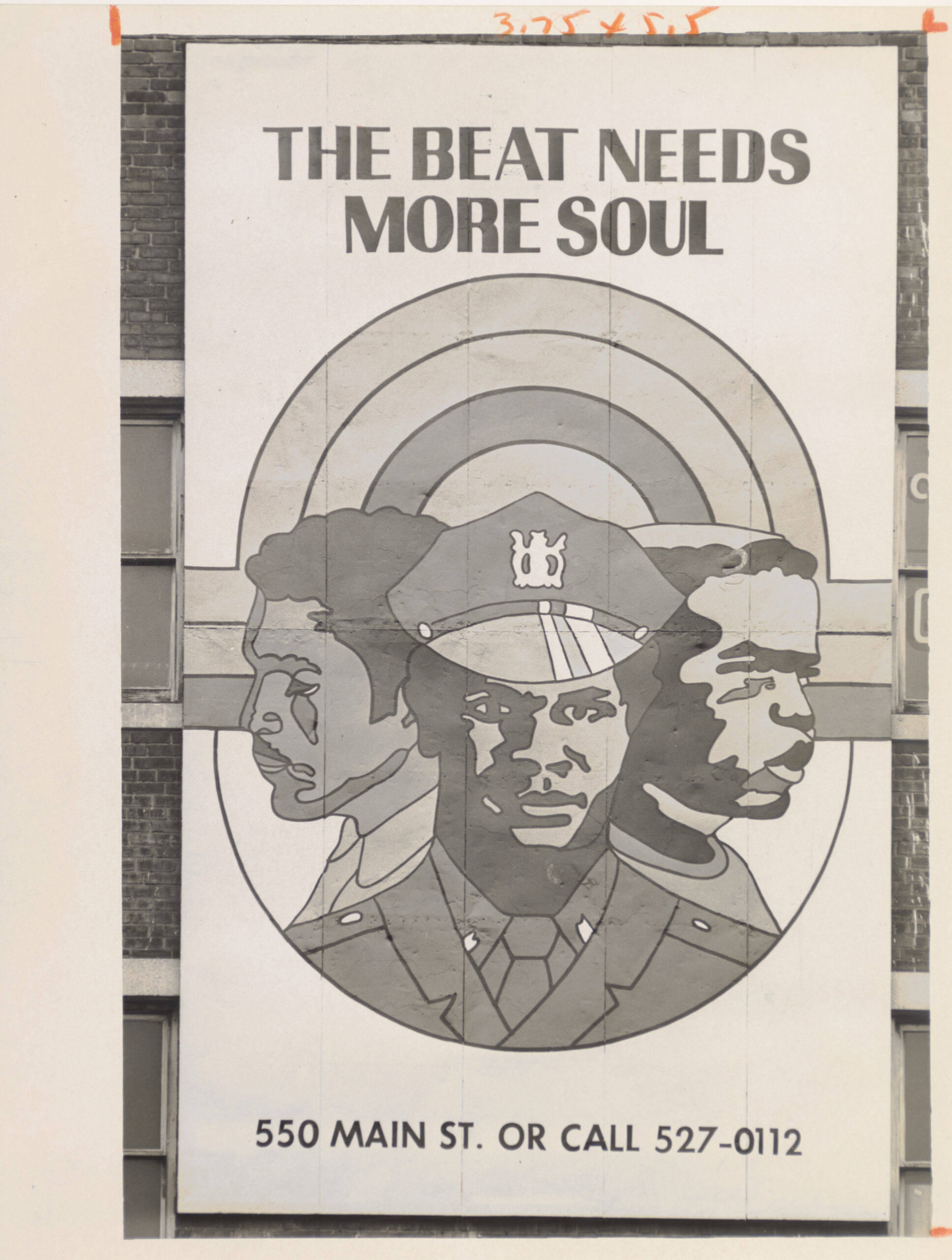

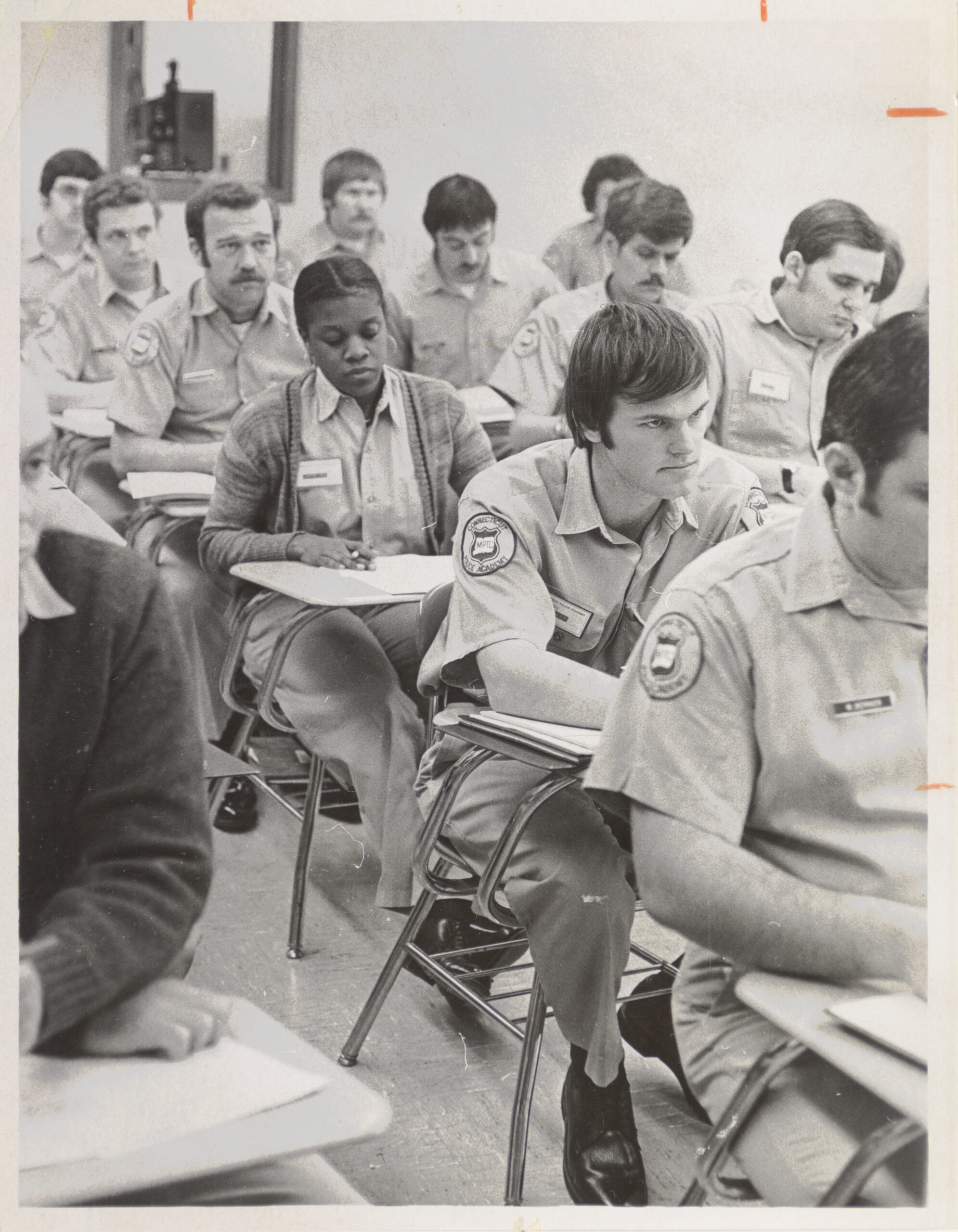

2017

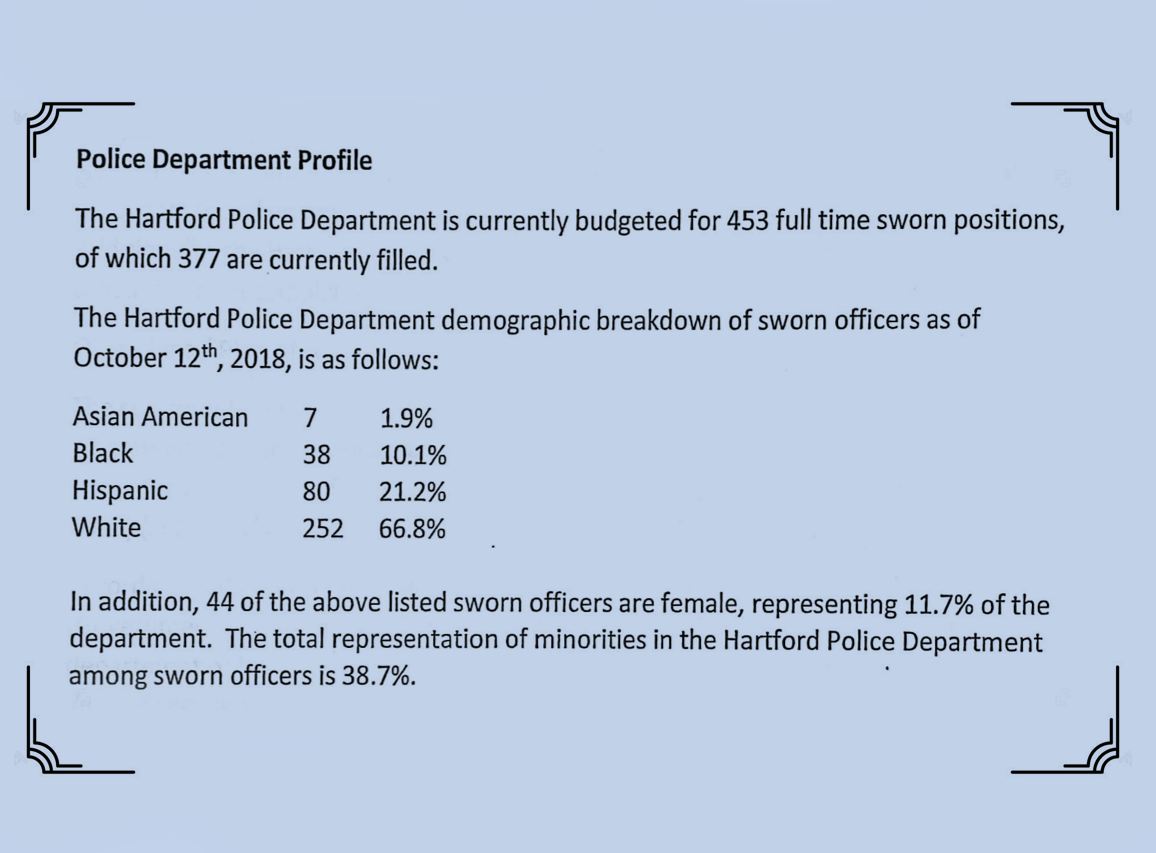

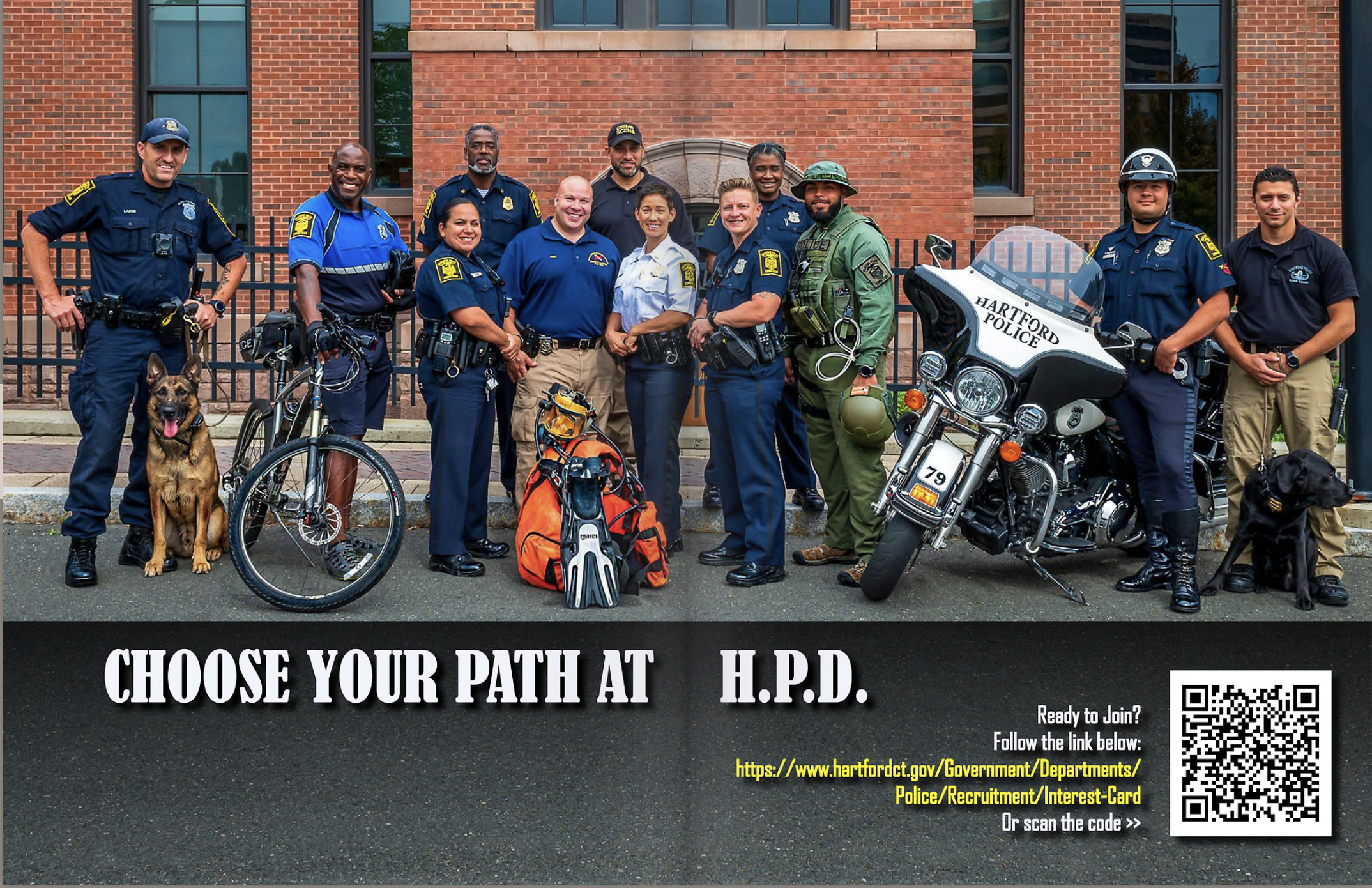

The HPD initiates a recruiting campaign aimed at increasing racial diversity on the force. Mayor Luke Bronin says that the current HPD recruiting class may be the most diverse group hired by the department, with “10 women and 5 ethnic minorities.”

2018

Plaintiffs file a motion for contempt alleging that there has been no improvement in HPD diversity since the consent decree was enacted, among other violations.

2019

Officer Noelia Resto was one of 40 officers to participate in Hartford Police Department’s body cam pilot program in February. Here, Resto shows how she’d turn on her body camera by pressing the large button in the center.

2020

In July of 2020, following the rising Black Lives Matter protests and national outcry against racial violence, Hartford council members request again that the federal court hold off on sunsetting Cintron. During this time, the Connecticut state legislature signed into law the Police Accountability Act. This relatively impressive piece of reformative legislation includes both performative measures and forceful ones, such as curbing qualified immunity.

2022

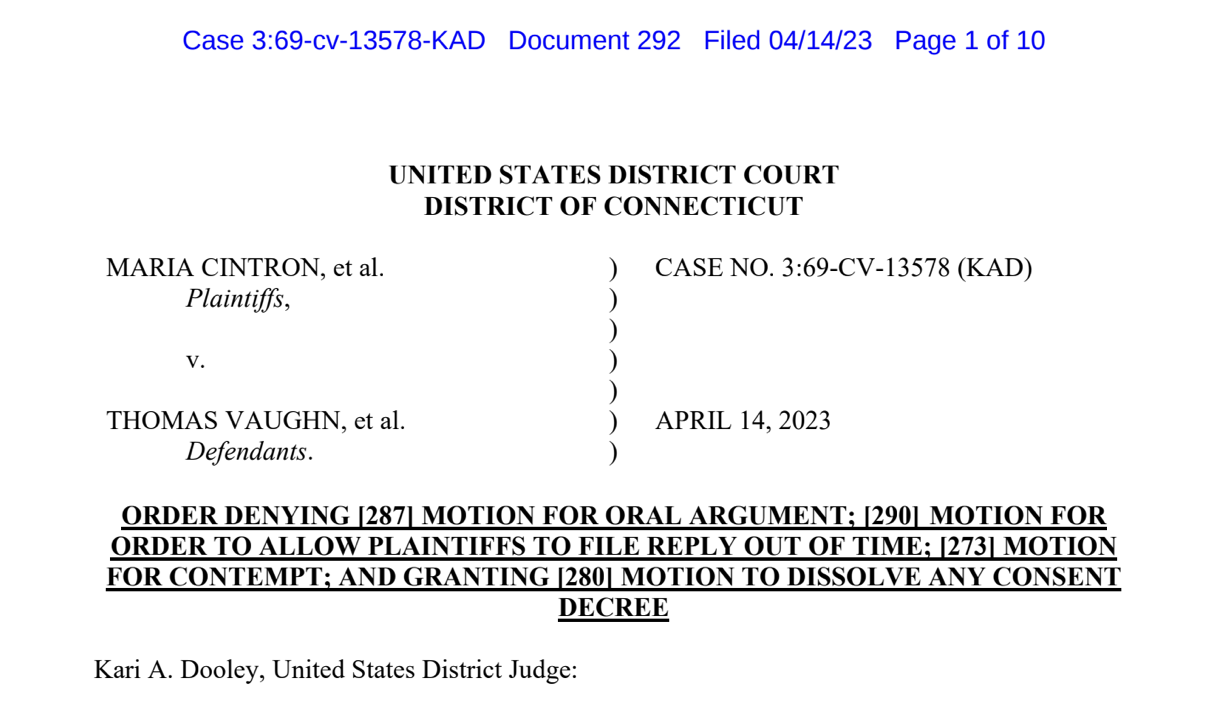

Plaintiffs file a motion for contempt and respond to an order to show cause in an attempt to prevent Cintron from being dissolved. Defendants oppose both motions, arguing that the HPD has made substantial progress and reforms in recent years.

2023

Judge Dooley dissolves Cintron, ruling all pending violations inconsequential. She affirms the intention of the consent decree, and recommends that future efforts of police reform move outside the judiciary.

The Dual Legacy of Cintron

Ultimately, the consent decree was terminated not because the HPD had fixed its systemic problems, but rather on the technical grounds that there was no proof it had directly failed to comply with the 1973 or 2010 agreements. The language in these motions was often aspirational and usually quite imprecise, which led to them holding little standing in the courtroom. The story of Cintron v. Vaughn searches for a path between the perceived potential and evident limitations of judicial police reform. Often, “justice” does not represent the totality of the facts, or the feelings of the public, or even the volume of harm caused, but rather a game played—earnestly—between narrow readings.

In her final order regarding the dissolution of Cintron, Judge Dooley affirmed the need for reform in the HPD, but felt that judicial oversight was no longer the appropriate arena in which to do so: “The next step in Plaintiffs’ continuing important and commendable efforts to promote diversity in the Hartford Police Department lies not with this Court, but with the police department itself, the City of Hartford, and the greater Hartford community.” What does this step look like? After city council resolved that the HPD institute its own policies to align with Cintron and that they publicize their progress, Council Majority Leader Thomas “TJ” Clarke II told the Hartford Courant that transparency was at the center of the resolution: “I think it’s important for people to know about their police force. What are the demographics of the incoming recruiting class? Or from an overall perspective, what is the composition of the Hartford Police Department? These statistics will now be accessible to everyone.” Is the force’s racial diversity—a concern which took the forefront in Cintron’s last leg of litigation, in Judge Dooley’s decision, as well as in the city council’s response—a promising avenue for decreasing discrimination in policing and advancing public safety? A full engagement with that question is beyond the scope of this project, but the history and discourse surrounding Black police officers in Hartford and beyond suggests that racial diversity is a complex and uneasy direction for reform.

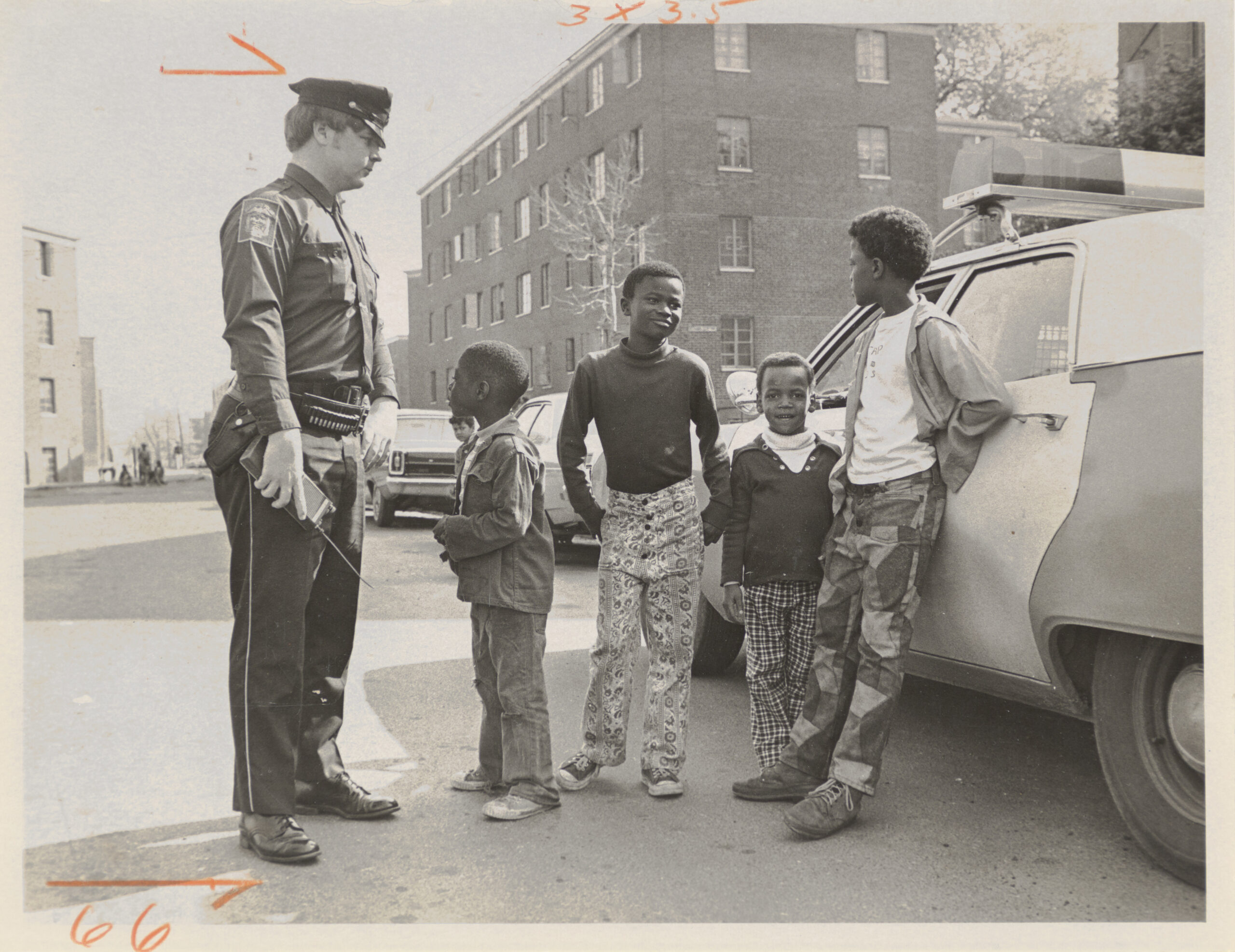

Using James Forman Jr.’s Locking Up Our Own as a point of departure, Devon Carbado and L. Song Richardson assess the complexities and contradictions of using racial diversity as a strategy to effect police reform, a discussion that provides insight into the situation of Deborah Barrows noted previously in 2000. Carbado and Richardson employ sociological, psychological and legal sources to explain the reasons that some Black police officers also exhibit racial bias and use excessive force against Black civilians, in fact, just as frequently as White officers do. Some of the causal factors they suggest, include: Black officers may simply have the same racial biases as White officers; they may experience “self-threats” or psychological threats to their selfhood which are then reaffirmed through demonstrations of authority; they may feel significant pressure to fit into their department’s culture; and finally, the structure and legal backdrop behind policing puts serious pressure on officers to overpolice poor areas predominantly inhabited by Blacks and Latinos. Currently, many police departments are significantly diverse; some, such as the LAPD, have a non-White majority of officers. Yet, this “progress” has not altered the structure of police power. Perhaps, this should serve to initiate a new set of questions and objectives beyond diversifying law enforcement.

Carbado and Richardson point to several recursive cycles which exacerbate overpolicing in Black communities, one of which is associated with “stereotype threat.” This psychological phenomenon, initially defined by Claude M. Steele, “refers to the anxiety that occurs when people are concerned about confirming a negative stereotype about a social group they value and to which they belong.” Ironically and tragically, when police officers are worried about people assuming they have racial biases based on police stereotypes, they may exhibit an increased propensity toward violence because they fear their legitimacy is threatened. Often, the officer’s authority is reasserted through force directed towards Black civilians, who have represented and imagined to be the prototypes and embodiment of criminality. This theory provides an insight into the deeply ingrained problems within police departments such as the HPD, which have been attempting to reckon with discriminatory reputations for decades. Despite the warnings which have long been raised by victims of over- and under-policing and astute commentators such as Carl D. Smith, whose article “Black Police and the Community” was published in the Hartford Star in 1970, racial diversity has remained a stable and unwavering aspiration within mainstream progressive visions of police reform. Carbado and Richardson conclude by asserting that “whether or not police officers are policing their own, if the broader structural forces we have discussed remain the same, the racial dimensions of policing with which the nation continues to grapple are likely to persist.”

If not racial diversity, what are other “next steps” for the HPD? One former officer feels that what Cintron lacked in scope was taken up by 2020’s Police Accountability Act. Perhaps the legislature, in its more direct relationship with the populace, is a better arena for these kinds of negotiations but time will tell. Outside the sphere of government, the media has been a moderately effective conduit for change, as seen in the department’s immediate response to the Hartford Courant’s 1992 investigation into police use of force case tracking. However, the media’s potential is quite limited to those few cases which become spectacularized, in part disguising their normality and providing the illusion of easy progress. Such raises the question as to whether this kind of publicized change may actually slow real progress, since it is easier to excommunicate the “bad apples” like Derek Chauvin than it is to address systemic issues which guarantee the continuance of racialized violence and discrimination under the color of law.

Judge Dooley’s decision to terminate the decree after fifty years caused great concern among community organizers and politicians in the city. Betts remarked that “We are deeply concerned that this dissolution of the consent decree will go in a step backwards for the city of Hartford and its residents.” and this was especially the case for “our Black and brown community members who have historically been targeted by discriminatory policing practices.” In keeping with the case’s inception, critiques of its dissolution are concerned with both over- and under-policing. While Betts advocated for judicial oversight to curb such issues as excessive force and discriminatory traffic stops, state NAACP leader Scot Esdaile pointed to the high rate of violent crime in Hartford, which saw “39 murders last year [2022]. Violence is out of control in our city, and this particular decree should not be sunsetted.” These responses to Cintron’s dissolution are not always directly tied to its actual functioning; in the public imagination, the consent decree wielded more power than it ever did in practice, suggesting that calls for racial equity represent a threat to the mainstream social order.

From 1973, Cintron was a statement of intention more than a method towards realizing significant change, and inertia tends to reign in matters of bureaucracy. City councilmember Joshua Michtom has perceptively noted: “[The] HPD remains allergic to transparency, reluctant to impose lasting consequences on officers who misbehave, and unrepresentative of the city it serves. More oversight can’t hurt. That said, half a century of federal oversight hasn’t fixed those problems, so maybe the lesson here is that federal oversight actually doesn’t help that much.” He further emphasized the wider social context in which policing functions: “In the end, I wish the city were more focused on making residents safer by giving them economic opportunities and improving their quality of life, instead of pouring more and more money into the police department. Ultimately a federal judge can’t make that happen.” To be sure, important tangible progress was made with regard to the civilian complaint procedure, the FDBI, and the investigations conducted into officer-involved shootings. But ultimately, Cintron’s value may have lied most in the space it opened for imagining alternative futures. The consent decree provided a field of potential in which competing visions of policing could be negotiated, albeit via the formal demands of the justice system. Even when faced with barriers to progress and resistance from the HPD, Cintron signified hope. The case empowered community members to demand checks on officers’ use of firearms, to ensure adequate investigations when members of the community were harmed or killed, and to name the language of harassment used by police as a mode of racial violence. The heart of the consent decree’s saga was its role as a vessel for public outrage and grief when community leaders exhumed it in response to the 1999 murder of Aquan Salmon. Its importance in that moment could not have been predicted when the case was filed thirty years prior, in 1969. Cintron was a potent acknowledgement, consistently re-affirmed, that the police are not infallible, that claims against them are legitimate, and that power is worth confronting.

Cintron landed far from the place where it began. Procedural reforms, such as racially diverse hiring, that would later take on primary importance, were not at the center of the plaintiffs’ complaint in 1969 when it was first filed. That document speaks to a more existential claim: that being denied protection and being harmed by agents of “public safety” is indicative of exclusion from the state’s vision of the public, which is to say, excluded from the category of the human. Maria Cintron’s witness statement, included in full below, describes that exclusion as it was expressed to her in the case’s founding incident: “The policeman never got out of his car. He never looked at my face, except to tell me not to frighten the man who beat my son after I told the man to stay away from him.” These experiences of dehumanization are fundamentally deeper than the proposed bureaucratic reforms of diversifying a homogenous police department, or firing one “bad apple” officer. The wide acceptance of such disrespect, reserved for those regarded as less than fully human, speaks to the integral fabric that binds the system of state control with dehumanization; one is intrinsically connected to, and informed by the other. The power of this statement is not measured by the changes it brought about; indeed, its power is evidenced by the lack of such change. Despite affecting the HPD’s activities for fifty years, Cintron’s foundational claims of dehumanization were too radical to be adequately addressed within the pillars of the same society which caused them. The plaintiffs in Cintron over its half-century tenure exhibited the precious bravery that has compelled every act of resistance across history, few of which have been heard, fewer of which have been heeded. The gap between the radical assertion and the clumsy machinery of its reception must constantly be tested if change is to occur. It is in this function that Cintron’s legacy continues to shine.