Original Cintron Plaintiffs: Organizational Representatives

E dward E. Goode

dward E. Goode

Reverend Edward E. Goode was an original plaintiff in Cintron v. Vaughan via his role as Vice President of the Hartford NAACP, and was a notable community organizer. Born in Boston, Massachusetts, Goode received degrees from Howard University and Yale Divinity school before going on to work in various churches across the Northeast as well as the Tuskegee Institute. He joined the Greater Hartford Council of Churches in 1967 as the assistant director of social services, focusing on housing, rehabilitation, health, and family life. By the next year, his focus had grown to include police-community relations. Goode was highly active in local political organizing, publishing his opinions on upcoming elections, housing issues and legislative changes via letters to the editor in the Hartford Courant. He attended the Black Power Conference in Newark, New Jersey in 1967, and developed nuanced views on the movement which he believed lacked clarity in its goals. In addition to his position in the NAACP, Goode was a member of the Coalition for Concerned People and sat on the board of directors of Hartford’s Legal Aid Society.

His stance on the civil unrest sweeping Hartford in the late 1960s, a major point of discourse amongst the city’s political groups, shifted over the years. In 1967, he signed a statement from a group of clergymen calling the riots a form of self-punishment within the city’s Black community; although an understandable response to oppression, they acknowledged, rioting constitutes a threat to anti-poverty programs and a hindrance to one’s future. By 1970, however, as the police became increasingly violent towards citizens during these disturbances, Goode had grown more sympathetic to rioting and civil disobedience altogether. In an article published by the Hartford Courant, Goode compared the recently established police curfew to the Antebellum South, and noted that rebellious enslaved people burned their own homes rather than their slaveholders’. He continued: “There is no commitment to human values in this town … The city is at war. 23 persons are shot and most people ignore it until it hits them.” Beyond the recent instances of police violence and the ineffective city council probe on police use of firearms, Goode was frustrated by the city’s failure to deliver on its commitments regarding housing and education improvements. “The children sense their oppression and pick up a rock,” he said.

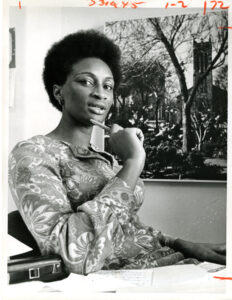

Glenda Copes Reed

Glenda Lorraine Copes Reed (1944-2013) was an original plaintiff as president of the Hartford NAACP in the late 1960s. She was an executive at Aetna insurance who advocated for corporate social responsibility throughout her lengthy career. A Hartford native, Reed earned degrees from the Hartford College for Women, Smith College, and the University of Connecticut. Copes was highly active in the NAACP youth task force, served as vice president of the larger branch, and eventually showed such promise that she was named president in 1968 at age 24. In this role, she was an original plaintiff in Cintron v. Vaughan. Copes was a visible proponent of police accountability within Hartford. She organized a memorial march for Dennis Jones, a sixteen year old boy who was shot and killed by officer Keith G. Marshall in 1969. The march was intended not only to honor Jones’ life but also, as Copes told the Hartford Courant, to “call attention to the conditions that brought about his death.” Copes was also part of the discussions leading to the Guardians’ strike that same year, in which the organization of Black HPD officers protested the department’s internal discrimination.

Copes’ expansive record of community involvement also includes serving as a director of the Hartford Public Library, holding various positions relating to housing rights and development, organizing voter registration workshops, drafting progressive housing policy for city council, and running a North End improvement campaign in which she herself participated, painting and cleaning homes of residents. She began her career at Aetna in 1972 as Manager of Urban Affairs, planning and implementing community programs in which the insurance titan could funnel its funds into the city to solve “urban problems.”

José Cruz

José Cruz was a Hartford public school teacher who began his career in politics in 1965, when he was elected first president of the Puerto Rican Democrats of Hartford, “the first specifically political organization of Puerto Ricans” in the city. Of the group, Cruz said “We have to make this community our community, and make it help us fight our problems.” Cruz became one of Hartford’s most influential Puerto Rican community leaders during the 1960s, implementing many social programs as director of the Community Renewal Team’s Clay Hill Multi-Service Center. He also served on the board of directors of the Urban League and the Hartford Public Library, was appointed commissioner of Hartford’s Human Relations Commission, and was named to the Connecticut Parole Board, among other positions. Cruz helped found Connecticut’s Puerto Rican Parade and wrote a column on Spanish News for the Hartford Times.

Cruz was elected president of the Spanish Action Coalition in 1969, the position through which he served as plaintiff on Cintron. The SAC was formed in 1967 by clergymen and Puerto Rican leaders, envisioned as an umbrella organization for Puerto Ricans as well as other Hartford residents in need of help. Their agenda was diverse to match their membership: winning council seats, educating voters, ending police brutality, and putting more Puerto Ricans on the police force. Cruz told the Hartford Courant that the SAC did not aim to represent Hartford’s latinx population, they were instead a group of individuals aiming to help them. In 1969, after Cintron was filed on behalf of the SAC among other organizations, the group slowly dissolved and its leaders created La Casa de Puerto Rico with funding from the Hartford Foundation for Public Giving. La Casa de Puerto Rico would become the home base of the Cintron Negotiating Committee after the shooting of Aquan Salmon in 1999 (see main timeline).

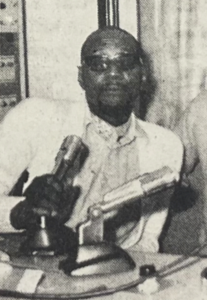

David Hudson

David Hudson

David Hudson was a prominent figure in Hartford’s media landscape alongside his work in political organizing. He was most known as a local broadcaster whose voice was familiar to many, a role which helped him draw attention to local issues as chairman of Hartford’s branch of the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE). Hudson spearheaded a rent strike in 1969 aimed at exploitative slumlords and pushed for community engagement efforts such as youth centers funded and controlled by locals. He was also interested in enabling more Black leadership in Hartford’s public education system. Hudson was involved in organizing for justice following the killing of Gary “Mike” Hansley by police officer Elden Thibodeau. He later chaired the Friends of Senator Smith organization, marking his close relationship to Senator Wilbur Smith, a Hartford politician and major political figure in the Black community.

Hudson’s media career was expansive; beyond radio, he was the director of Hartford’s Community Film Workshop and chairman of the Hartford Communications Committee. He was also involved with several local Black papers; he ran a column in the Hartford Star called “Community Opinions,” in which he provided a platform for a range of Hartford residents to share their opinions on pertinent issues including civilian review boards and police killings of Black youth. After the Star dissolved due to financial constraints, Hudson became President of the board of directors of the New England Voice, a new Black paper. He was also briefly editor-in-chief. Hudson was a proponent of Black Nationalism as a strategy of community uplift in the late 1960s, and said in a CORE statement that Hartford’s riots would be seen historically as “the true beginning of the Black Revolution here … perhaps now they will be recognized for what they are—rebellions against oppression and exploitation.”