Politics and Policing in Hartford, 1970

A prevalent theme running through this report is a feeling of desperation and a sense of urgency concerning the growing polarization between the police and the communities at large, and in particular, the non-white communities.

—“Status of Police-Community Relations in Nine Connecticut Cities: A Preliminary Report,” prepared by the Connecticut Commission on Human Rights and Opportunities (CCHRO), December 1970

Introduction:

In November of 1970, the Connecticut Legislative Commission on Human Rights and Opportunities commissioned a report on “police-community relations” in Connecticut’s cities, hoping to gather a range of perspectives on an issue that had been animating public tensions and political conflict in recent years. The study’s interviewers realized the difficulty of the task at hand, and the complexity of the subject, when their respondents questioned the value of the term “police-community relations” itself; “the term has been used quite frequently but never clearly defined.”1 One respondent summed up the issue with striking lucidity, explaining that “the term ‘police-community relations’ had come to be another way of indicating racial strife. The entire issue, he felt, had boiled down to a ‘black citizens vs. white establishment’ conflict.”2

This project attempts to give shape to a certain landscape, one that could be mapped as “police-community relations” in Hartford around the year 1970, but is encountered as rockier territory. Lusher, too.

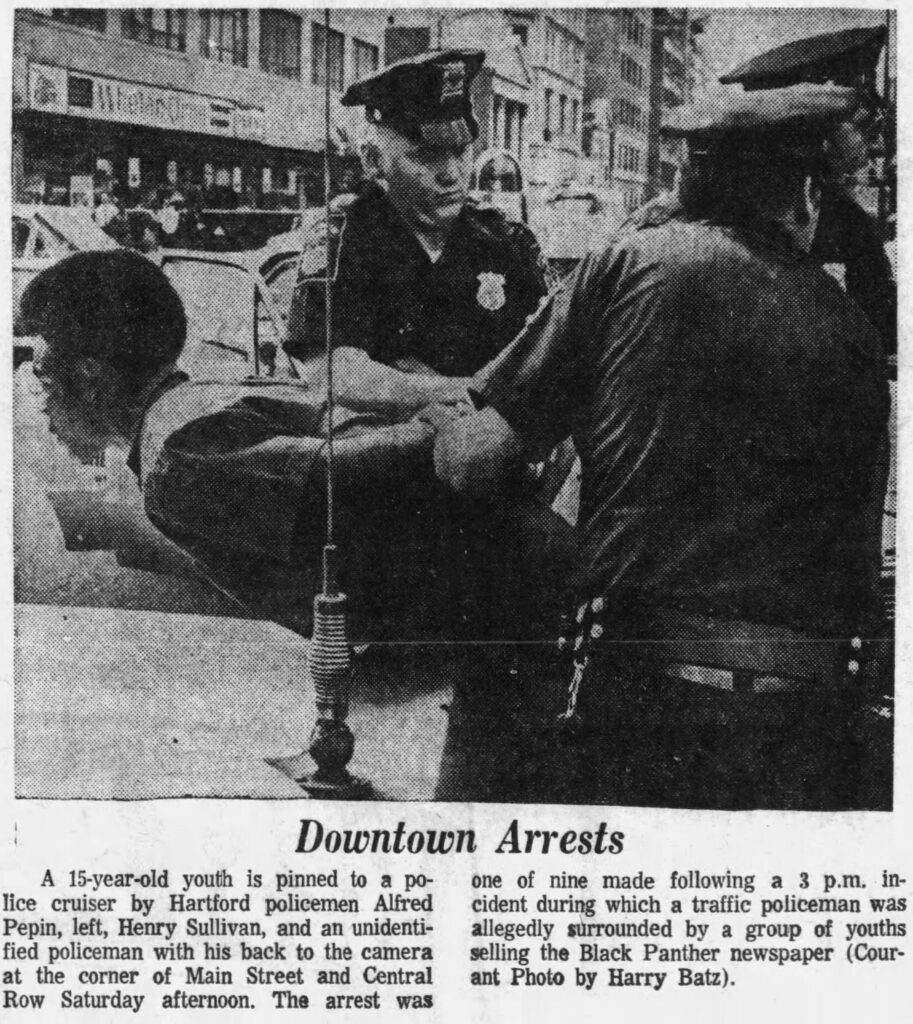

This study aims to bear witness to some of the deaths and debilitating injuries suffered by Hartford residents, mostly young Black and Latino men, at the hands of the Hartford Police Department (HPD) in 1970 and the years immediately before and after: Dennis Jones, Charles Jones, Gary “Mike” Hansley, William Casey, Abraham Rodriguez, Efrain Gonzalez, and James McMillan. These acts of violence had a profound effect on the city’s political scene and the lives of North End residents, a working-class and predominantly Black and Puerto Rican section of the city. Each tragedy was met with tremendous efforts of resistance and political organizing which served as some of the only checks on police power within a regime which was, as is typical, highly deferential to those “brothers in blue.” The names of these men have not been spoken in the public sphere (to this author’s knowledge) since the 1970s, so this text hopes to serve as an archival intervention unearthing stories which should never have been overlooked.

What follows relies primarily on research conducted in newspaper archives online and in physical collections at the Hartford History Center and the Connecticut State Library. The most significant publication used is the Hartford Courant, the city’s largest and most active daily, which is entirely digitized. Another valued resource is the Hartford Star, the city’s foremost Black paper which went out of print in 1974. This methodology is replete with limitations, and the space that the Courant takes up means that the coverage of events is biased toward the largely white, middle-class perspective of that publication. If police-community relations boils down to “black citizens vs. white establishment,” as one Hartford resident put it in the CCHRO report, the Courant usually sympathizes with the latter. The research process for this piece required constant vigilance in order to stay aware of the ever-present narrative scheming of this white morality, with its racism, classism, and particular valuation of human lives. One shining outlier within the Courant is the work of reporter Theodore Driscoll, who covered Hartford politics during this era with nuance, distrust of the police and city administration, and respect for the city’s Black and Puerto Rican activists. Some highlights from his writing are featured in the section below titled “City Council Committee on Police Use of Firearms.”

Certain cases of police brutality have received major media attention in recent years, raising public awareness of a leading cause of death among young Black men, a distinctly American epidemic. However, these prominent stories risk presenting deadly force as less commonplace than it is by dramatizing specific cases; they lead to performative reform measures that do little to change the structures of power which enable, or in fact require, that police continue to oppress vulnerable populations in the register of the mundane and everyday. The stories included here are an index of a particular law enforcement agency’s valuation of human life, which is of course continuous with good American values.

This narrative is continuous with its sister section in the CCP, our study of the HPD’s consent decree, Cintron v. Vaughn. What happened in 1970 provided context and fuel for the class action lawsuit filed against the HPD in 1969 by representatives of Hartford’s Black and Puerto Rican communities. Cintron became a federal consent decree in 1973, enabling judicial oversight of the HPD which lasted until 2023, the longest tenure of this kind of reform measure in US history. Although this story is filled with tragic events, it also offers a history of imaginative public safety that can inspire local efforts on a similar scale. Consider the Oakland Civic Patrol, in which volunteers provided effective community protection in the early 70s; the Guardians, an organization of Black HPD officers who protested internal discrimination and police brutality among their own; or the Concerned Citizens, who offered a model of complaint collection that was more accessible than Internal Affairs. These local actions formed a foundation for faith in change, a commitment which has always required nurturing in the face of power.

Police Violence Early 1970s

Dennis Jones

Dennis Jones, sixteen, was shot and killed by West Hartford Police Officer Keith G. Marshall in August 1969 as he fled a stolen car. Like many other Connecticut officers who killed young men in this era, Marshall was absolved of responsibility because Jones had committed a felony, empowering officers to shoot in order to prevent escape. This rule would later be ruled unconstitutional by the US Supreme Court in 1985’s Tennessee v. Garner. Jones’ mother lost a lawsuit the next year alleging negligence on the part of Marshall and violations of her son’s constitutional rights.

Charles Jones

Charles Jones, thirty three, was shot in the head by Officer Daniel Herbert shortly after 3 am on September 2nd, 1969. Officer Herbert claimed that Jones had been looting the nearby 5 and 10 store; four witnesses claim he was just standing there. Jones was a prominent community worker who served as chairman of Model Neighborhoods Inc. He survived the shooting with severe brain damage and paralysis of the right side of his body. He sued in 1973 and lost.

Gary “Mike” Hansley

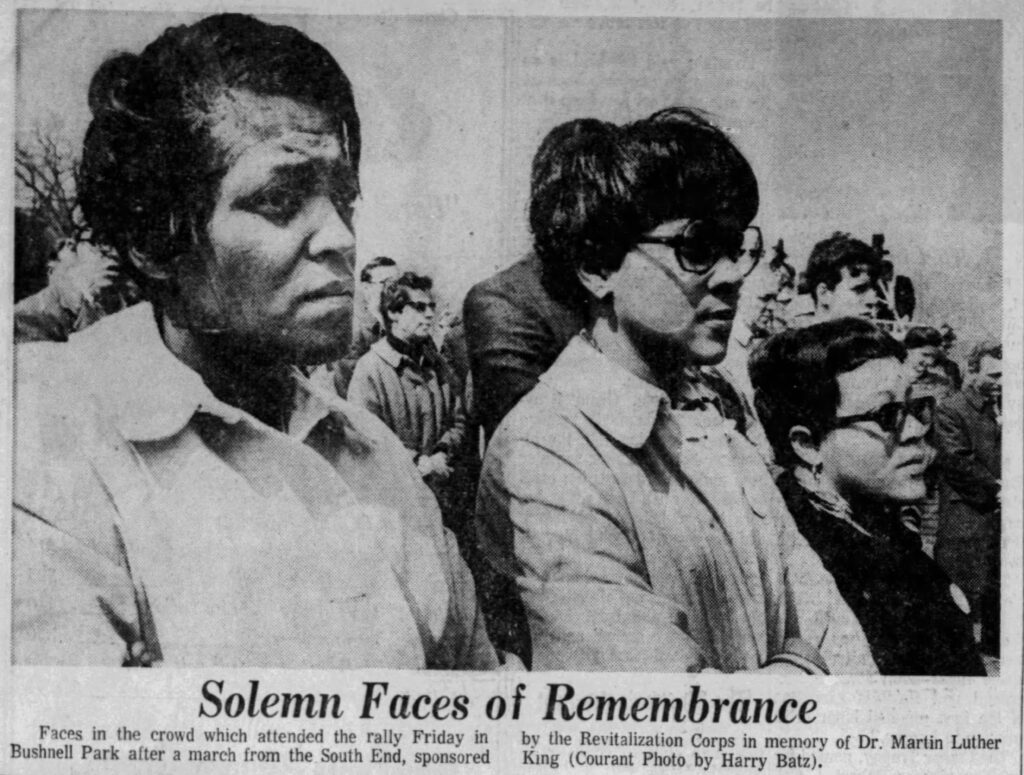

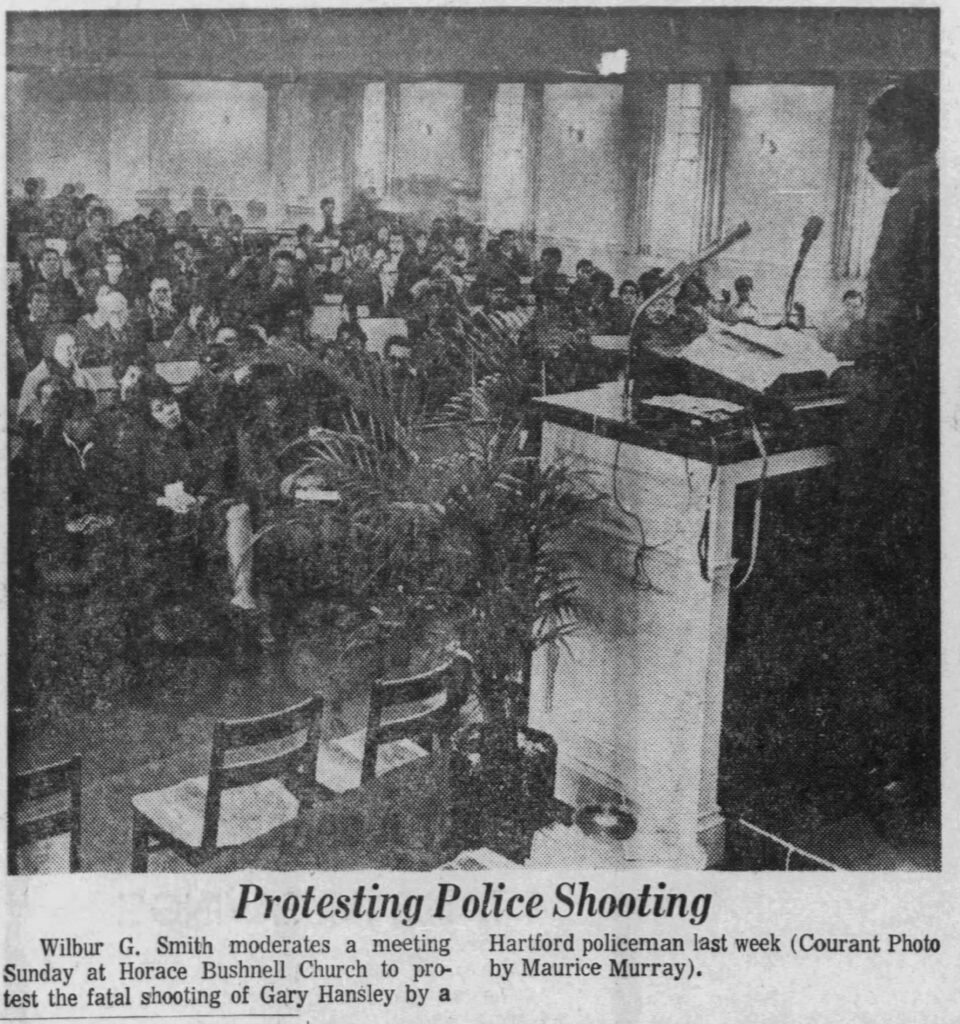

Hansley, nineteen, was shot and killed by officer Elden Thibodeau after stealing a purse on March 14th, 1970. Thibodeau had acted within city guidelines which permit police officers to shoot in order to apprehend fleeing felons. The killing led to wide community outrage and spurred a wave of organizing to investigate the Hartford Police Department’s use of deadly force.

William Casey

On March 31st, 1970, Officer David Quirk followed William Casey to his home after he ran a stop sign. Casey resisted arrest and attacked Officer Quirk with a pocketknife, and Quirk shot him four times in self-defense. Casey survived with serious injuries and was later convicted of aggravated assault and resisting an officer.

Abraham Rodriguez

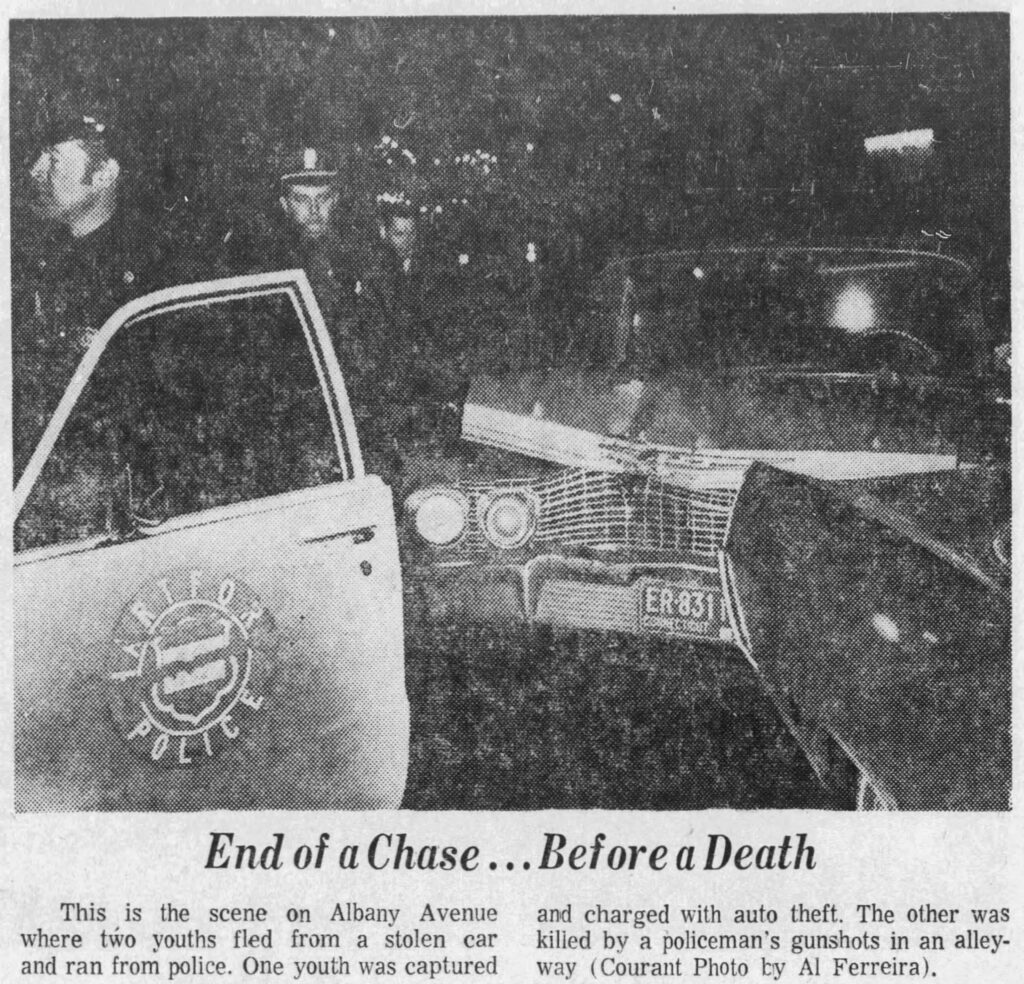

Officer Anthony Lombardi was in a car-turned-foot chase with nineteen-year-old Abraham Rodriguez. Lombardi shot and killed Rodriguez after cornering him in an alley. Lombardi was arrested for manslaughter, showered in public support, and then acquitted.

Efrain Gonzalez

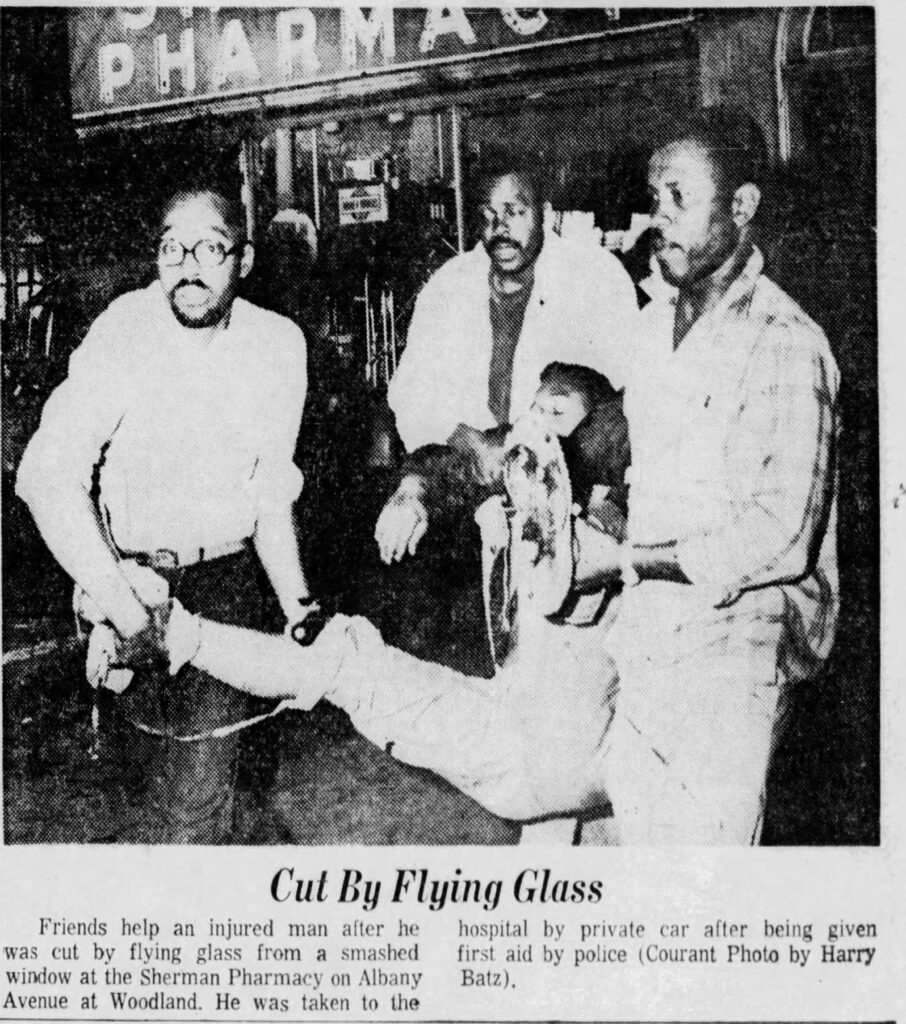

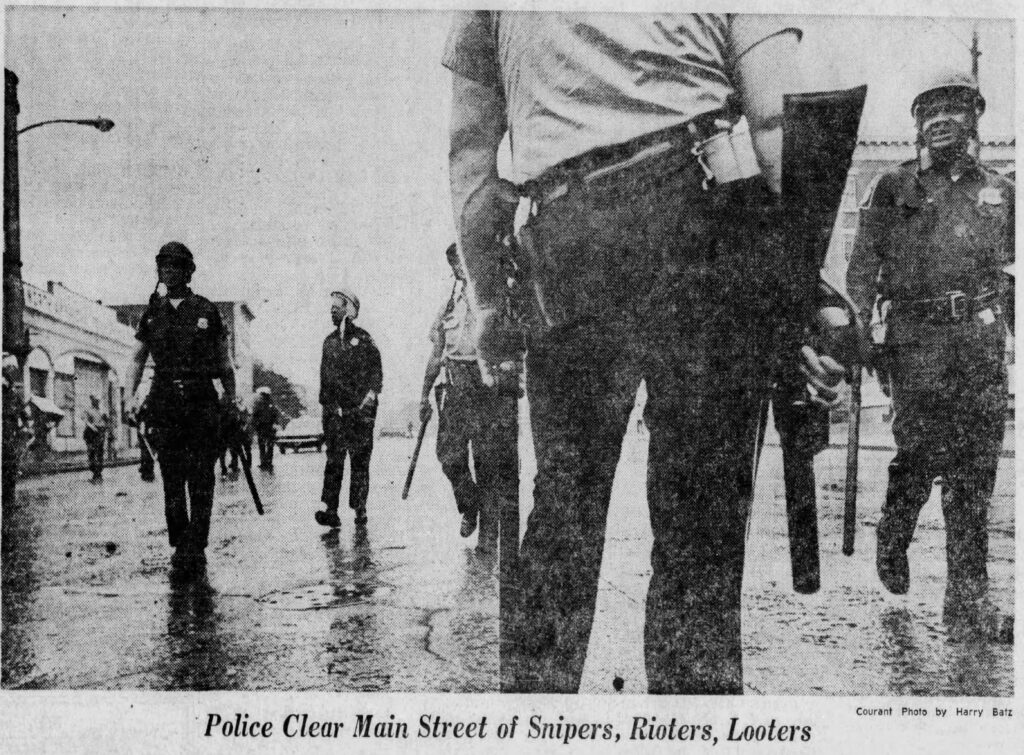

Efrain Gonzalez was killed with double-zero buckshot without provocation during a civil disturbance in July 1970. The coroner declared he had been shot by a policeman whose identity did not need to be discovered because he was not criminally responsible. The Gonzalez family filed a civil lawsuit against the city and members of the police force in 1971 and lost in 1975.

James McMillan

On May 3rd, 1971, twenty-three-year-old Hartford resident James McMillan was shot and killed by Bristol Police Officer Thur Hewitt while running away after being apprehended as a shoplifting suspect. After protests, Hewitt was suspended without pay because he had disobeyed the Bristol Police Department’s policy on deadly force, which is narrower than Hartford’s. The coroner’s report found Officer Hewitt criminally responsible for McMillan’s death, but the state’s attorney still decided not to prosecute. McMillan’s mother Leona sued Hewitt and the town of Bristol. There is no coverage of the outcome of the case, and it is safe to assume she lost, considering the failure of all similar cases during this time.

City Council Committee on Police Use of Firearms

Abraham Rodriguez’s death (see above) was the third police shooting in Hartford within a month, and the second fatality. On March 14th, 1970, nineteen-year-old Gary Hansley was killed by plainclothes Officer Elden Thibodeau (see above, Gary “Mike” Hansley). On March 31st, William Casey, thirty nine, was shot four times outside his home by Officer David Quirk (see above, William Casey). Both victims were Black. The officers were found to be acting within department rules, which allow them to shoot in self-defense, or to stop a felon from fleeing. After Hansley’s death, several mass rallies were held and community leaders demanded more strict guidelines on police use of guns. At a city council meeting on March 24th, Mrs. Regina Brown, a youth counselor at Horace Bushnell Church, read three community resolutions that had arisen through meetings and rallies at Horace Bushnell Church (see above: Gary “Mike” Hansley; Community Response).

The Guardians

The Guardians are an organization of Black Hartford police officers founded in 1962 and still active today. In the late 1960s, they began organizing to demand that the department address racism within its ranks and administration. The first major action occurred in the summer of 1969, during which the Guardians released a list of grievances regarding discrimination within the HPD and orchestrated a sick-call protest. They received support from the Council of Police Societies, a national organization of Black police officers. The next year, the Guardians released a statement vowing to physically intervene should they witness bigotry or racial violence by a white officer. The Guardians continued to organize around internal discrimination through the 1980s, but no longer hold that role.

Conclusion:

A month after the city council committee on police use of firearms submitted their recommendations, requesting no change in guidelines governing deadly force, the Connecticut Commission on Human Rights and Opportunities—led by Arthur L. Green—released their report on police-community relations in nine Connecticut cities. The report offers a straightforward structural assessment as explained by two respondents, out of a pool sourced from various sections of Hartford society.

Two interviewees attributed the problem to current political situations: The population to which a city agency, such as the police department, has traditionally been accountable has moved and been replaced by a vocal non-white population. This non-white population is demanding service from the police, while the police department is continuing to hold itself accountable to other segments of the population. Meanwhile, the non-white ghetto residents have not yet developed the political power to hold City Hall accountable to themselves. Thus, tension and conflict have been produced.

This quote gets to the center of Hartford politics in the late 1960s and early 1970s. Notably, the report writers are unable to refer directly to white society, defining it only by negation via the “non-white population.” This veil, implicitly upholding white supremacy by naturalizing and erasing its particularity, underscores the profound shift seen during this era in US politics as marginalized voices grew in strength and number. The white establishment (encapsulated here by the HPD administration and city government) struggles to account for itself amid a changing landscape. According to the report’s interviewees, this moment of fissure—marked doubly by a lack of language—was viewed at the time as a turning point in which the scales of power were wavering, to uncertain end.

Around 1970, the city government and Connecticut judicial system failed repeatedly, from the perspective of Hartford’s Black and Puerto Rican organizers, to enact justice or show respect for the lives of those living in the North End. Viewed from the perspective of this moment of shifting scales, the story is not simply one of defeat and could be re-narrativized as one of waver. Local leaders did not falter in their demands after the city council decision; amid the many lost civil suits in which no damages were awarded to the families of brutality victims; alongside the HPD officers still roaming Hartford with bloodied hands. They continued to pour effort into this fight, a story taken up again in 1973 with a significant victory: the class action lawsuit Cintron v. Vaughan, settled via consent decree, effectively institutionalizing the voice of civilian critique of the HPD for fifty years.