1960s

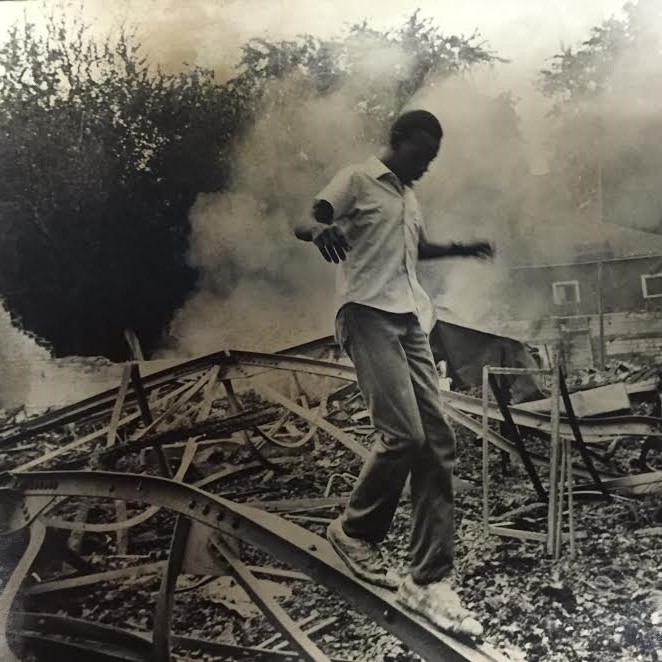

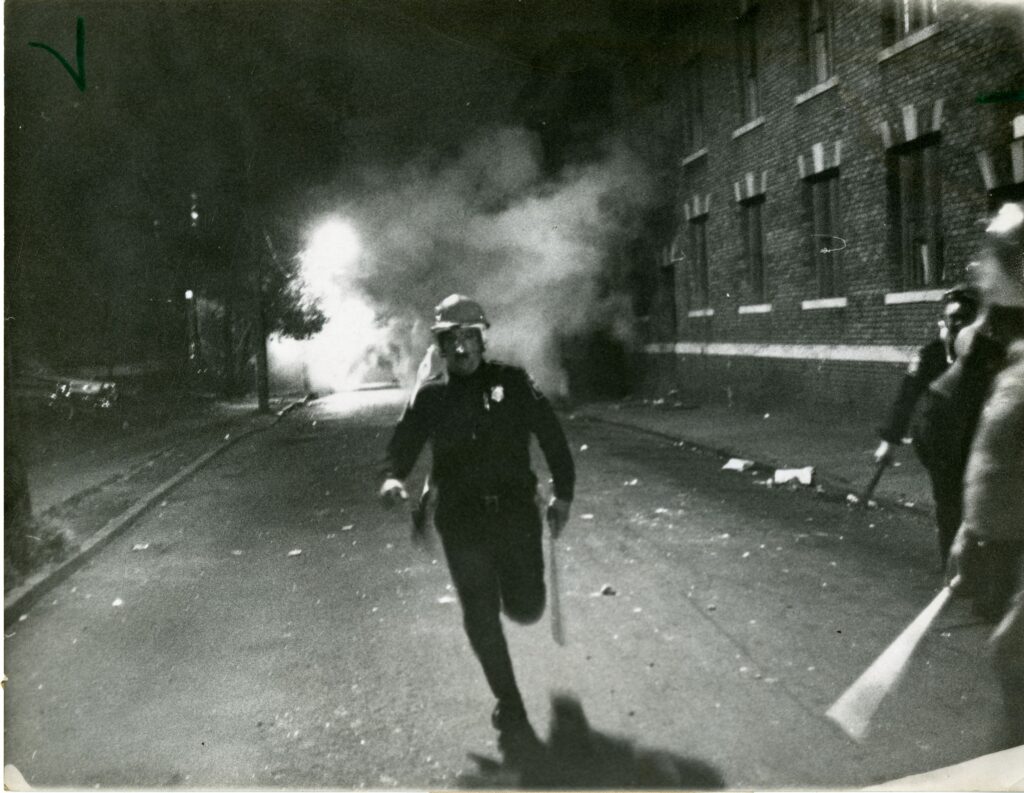

In 1960 at the tender age of six, Ruby Bridges had to be accompanied by four deputy U.S. marshals to William Frantz Elementary School in New Orleans, a moment iconized by Norman Rockwell in his now classic 1964 painting, The Problem We All Live With. The problem of racial conflict, only intensified during the 1960s, being marked by assassinations of major political figures – Medgar Evers, President John F. Kennedy, Malcolm X, Reverend Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. As well, the decade came to be defined by uprisings in Harlem (1964), Watts (1965), Detroit and Newark (1967), and in 1968 across many cities in the wake of the assassination of Martin Luther King, Jr.

These rebellions stemmed from historical racial dynamics including social/educational segregation, economic inequality, and the lack of an ability for Blacks to exercise constitutionally guaranteed rights. Another ongoing issue that also helped to spark these uprisings, was the history of excessive force utilized by law enforcement agencies.

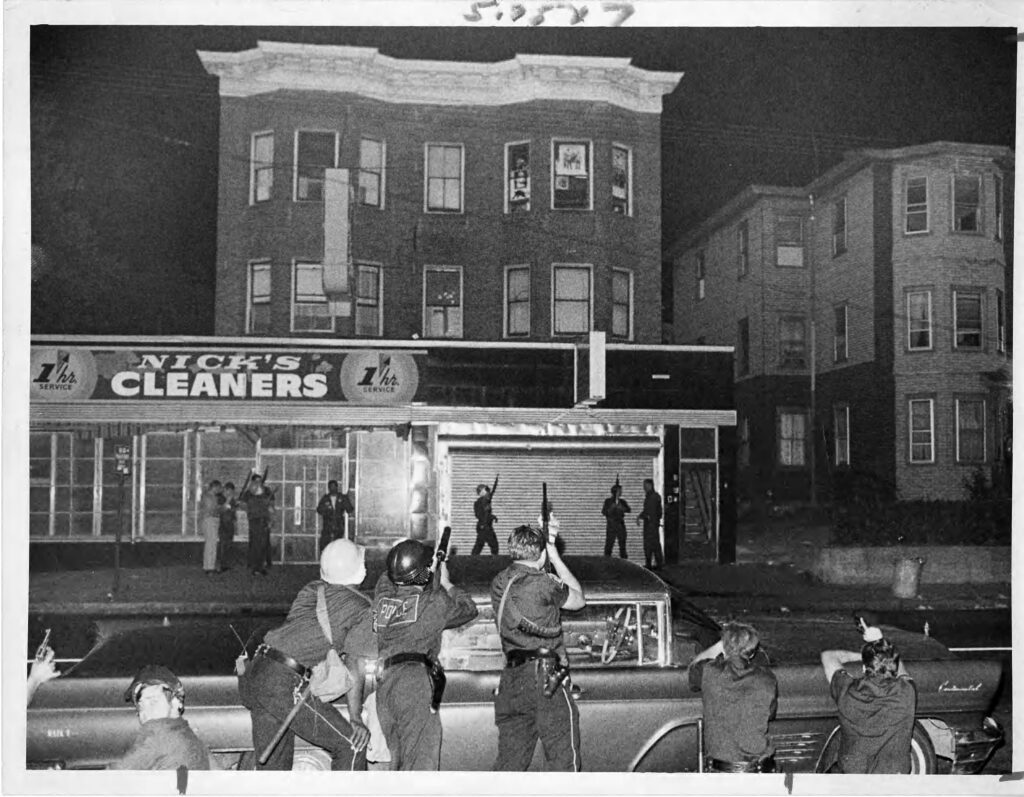

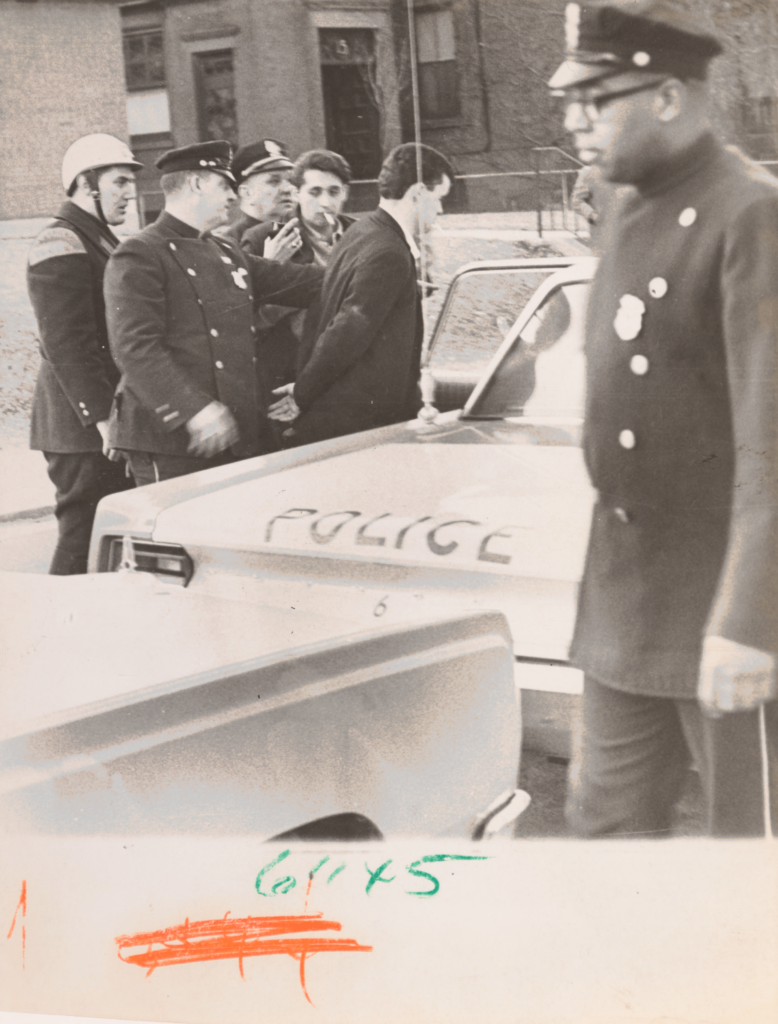

In December of 1969, Blacks and Puerto Ricans1 (as they were identified at the time) file a class action lawsuit against selected city officials and the Hartford Police Department. The suit alleges that officials of Hartford city government, including the chief of Police (Thomas Vaughan), city manager (Elisha C. Freeman), director of personnel (Robert Krause) as well as several police officers, subjected residents of the city to a “systematic pattern of conduct consisting of violence, intimidation, and humiliation” and thereby denied them rights and privileges guaranteed by the Constitution.

Many charges are enumerated in the lawsuit, including employing unnecessary deadly force, using trained dogs and tear gas against the plaintiffs, and arresting residents for attempting to exercise their constitutional rights. However, none of these were the first claim mentioned. Notably, the first charge concerned the treatment of the residents in an abusive manner that lacked recognition of their humanness: “a. Committing acts that have no purpose or justification other than to humiliate or degrade members of plaintiffs’ class.” This issue was related to a subsequent charge in the case: “g. Habitually referring to members of plaintiffs class with humiliating, derogatory, and obscene racial epithets and in numerous other ways refusing to accord members of the plaintiffs’ class respect due to citizens by officers of the law.” These two charges illustrate the systemic nature of disrespectful behavior displayed toward the Black and Puerto Rican residents of Hartford.

Relatedly, another issue which initially prompted the class action lawsuit, did not involve overpolicing, but rather stemmed from a case of underpolicing, which was also charged in the lawsuit: “h. Habitually denying plaintiffs and members of the plaintiffs’ class the same police protection from criminals, crime, and anticipated crime…” On August 26, 1969, ten-year old Roberto Cintron, one of the sons of the main plaintiff Maria Cintron, was repeatedly slapped by a White man.2 A half hour after the incident, a police officer arrived, and asked Cintron whether she wanted the man to be arrested, to which she replied yes. The man apologized and said that he had an “Irish temper.” The officer excused the man’s behavior, adding that “he had to protect himself.” To this assertion, Cintron responded: “maybe so, but not against a ten-year old boy.” Cintron admonished the officer for failing to do his job. “The policeman never got out of his car,” she wrote in testimony towards the class action lawsuit that was to come. “He never looked at my face, except to tell me not to frighten the man who beat my son after I told the man to stay away from him.”3

Like the cases of Ruby Bridges, the Little Rock Nine, or the Topeka parents in the Brown v. Board of Education, an incident involving the treatment of a child was utilized to challenge the system of racial hierarchy, but in this instance it involved policing. The plaintiffs called for measures that would reform the Hartford Police Department, including: the desegregation of the various units of the department (vice squad, burglary squad); changing the requirements for recruiting officers; recruiting members from the plaintiffs class; and “reducing the minimum height requirement to allow the inherently shorter Puerto Ricans – Spanish Americans to qualify.”

The Cintron v. Vaughn case did not go to trial but rather in 1973 resulted in a consent decree with the Hartford Police Department. This outcome provides a useful lens through which to understand the history of policing in the United States. It is perhaps the longest consent decree to have been initiated with law enforcement, and that such occurred in the liberal North versus the formerly segregated South is worthy of note. As well, that the case was not directly prompted by discriminatory police behavior but rather on an incident that called for police intervention demonstrates another reason for further examination, which itself is a reflection of issues beyond policing that deal with who deserves protection and who can be treated without regard.

Notes

1. Although common parlance would prefer the generalized term “Latinx,” we use the particular, “Puerto Ricans,” because this is how the group self-identified at the time and it is more accurate.

2. In contrast with capitalization norms at present, we have chosen to capitalize “White” as well as “Black” because both are ethnic groups. This choice is not intended to show respect toward Whiteness or to elevate White identity. It is a gesture that aims to undo the term’s universality.

3. Plaintiffs’ Exhibit A in Support of Plaintiffs’ Motion for Order Precluding Defendants from Opposing Claims, Cintron, et al v. Vaughn, et al, 3:69-cv-13578-KAD (D. Conn. November 24, 1970).