2020

In the wake of George Floyd’s murder at the hand of Minneapolis Police Officer Derek Chauvin and the subsequent movement of protests nationwide, many police departments feel pressure to revisit their policies regarding use of force and officer accountability. In Hartford, city council members revise the municipal code governing the Civilian Review Board to enable more community input into the selection of board members.124 Council members also renew their request that the federal court not sunset Cintron until more progress is made towards officer accountability and department diversity. Reference to the national atmosphere is made explicit in the resolution:

WHEREAS, during the last few months, our nation has been ethically and morally racked by the murder of people of color by members of different police departments around the country; and WHEREAS, these murders have resulted in rioting and civil unrest in all corners of our nation; and WHEREAS, the Cintron v. Vaughn Consent Decree and the related communication and negotiations between the Plaintiffs and the Hartford Police department is one of many tools to foster racial and disciplinary progress in the Hartford Police Department; and WHEREAS, such avenues of reform and progress in how our City polices its communities is necessary and critical especially at this time in our nation’s history…125

This resolution gestures toward a recognition of the structural dynamics of policing in Hartford, although it questionably locates deaths caused by police officers elsewhere—in “different police departments around the country”—rather than acknowledging those that have occurred at home. Indeed, in 2019, there were 66 police killings in Connecticut, most of which did not result in any legal action being taken by state’s attorneys against the police officers.126

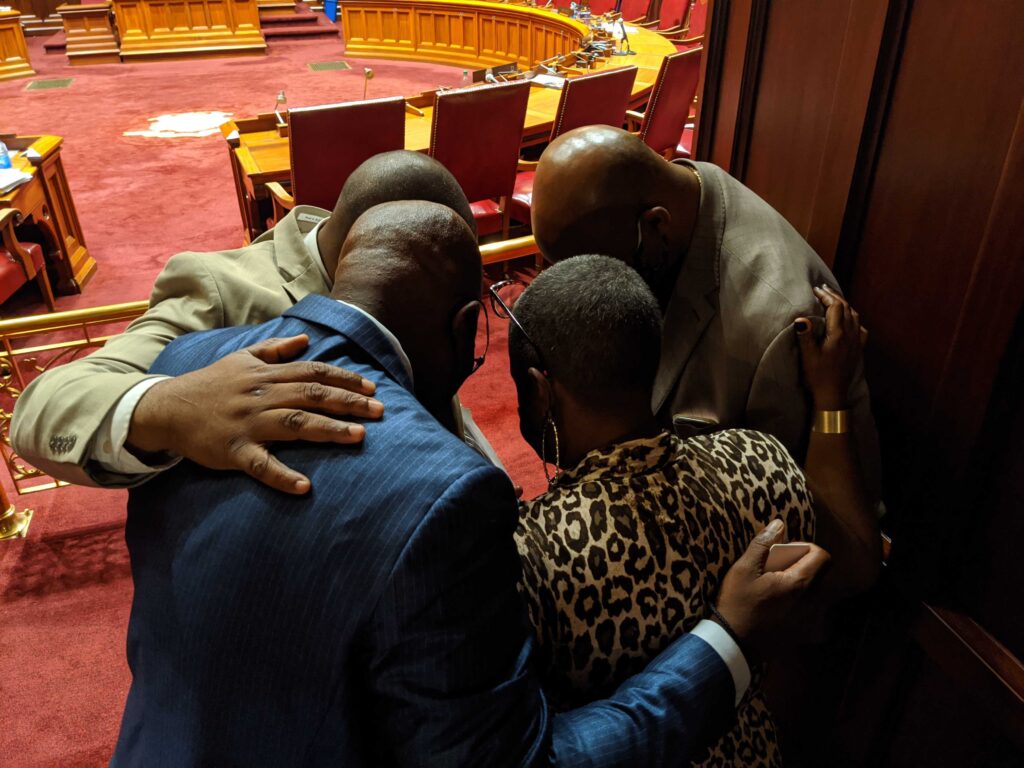

Without questioning the motivations of decisions made under public pressure, Connecticut’s General Assembly signed into law an impressive piece of reformative legislation, An Act Concerning Police Accountability. It includes a range of reform measures relating to police operations, legal accountability, and decertification. Melvin Medina, public policy and advocacy director of the ACLU of Connecticut, spoke about the meaning of the act when its passage was announced.

People have spent years telling the Connecticut General Assembly that police violence and racism exist in Connecticut, have gone unchecked, and that families harmed by police are denied justice and redress. Ending police violence will not be solved by any one bill, but the bill passed out of the legislature today is a start. The legislature must take stronger action in future sessions to end systemic racism and violence in policing, and policymakers must recognize that their work has only just begun. We applaud the majority of legislators who, in an act of solidarity with their Black and Latinx colleagues, voted to better protect the public from police violence. To the legislators who instead voted to shield the profession of policing from accountability, do better.127

As Medina emphasizes, the act is a beginning. Despite being lauded in the media, some provisions are highly unlikely to occur, such as a rule that officers intervene when they witness their cohort using excessive force. The rule was inspired by footage of George Floyd’s death which was circulated widely on the internet during the summer of 2020. The effectiveness of this measure remains questionable. In past attempts when some Black officers attempted to hold their peers accountable, such as Gerald Pleasent and the Guardians in 1970 (see Guardians; Lyric Dance Hall Disturbance), they have not been supported. Indeed, scholars of policing find gestures such as the intervention rule to be performative, noting that an officer’s use of force is usually rationalized and justified according to their department’s culture (and often their individual temperament) rather than according to the letter of the law. This understanding was prevalent during Hartford’s citywide debates surrounding deadly force in 1970 and continues to reverberate. During the 1970 City Council probe into police use of force, committee members minimized the saliency of written rule as a rationale behind their decision not to recommend stricter guidelines: “No matter what the guidelines, whether they are made more loose, or more restrictive, when the police officer exercises judgment in a split-second what really comes into play is his training, his deportment, his attitude, his intelligence, good judgment, discipline as well as self-discipline.”128 Additionally, the 2020 law underestimates the power of the bonds created among officers, the “brothers in blue” who remain steadfastly resistant to interference from those outside their cohort.

Another questionable provision of the act is the mandatory use of body-worn and dashboard cameras. Despite its promises of accountability for police behavior, this technology has been shown to be ineffective. A 2019 review of seventy studies of body-worn cameras (BWCs) concluded that “Although officers and citizens are generally supportive of BWC use, BWCs have not had statistically significant or consistent effects on most measures of officer and citizen behavior or citizens’ views of police.”129 Should a civilian file a complaint charging mistreatment by a law enforcement officer, internal affairs usually views the footage of the incident through the lens of the value system of policing which almost always condones the officer’s actions. Within this matrix, the ostensible objectivity of video as incontrovertible evidence provides no more assurance of accountability when a violence incident occurs than the weight of a victim’s words. In contrast to expert consensus on the ineffectiveness of body and dashboard cameras, much of the public maintains a deep faith in this technology, perhaps because sight is privileged among the senses as the truest form of perception. i.e. seeing is believing. Thus, as in the case of the iconic video of Rodney King’s brutal beating, an interpretation of such encounters pre-existed the actual occurrence of the incident, against which in the popular imagination, the technology’s lack of efficacy does not seem to militate.

Despite making perfunctory claims, the Police Accountability Act also includes potent changes that could potentially change the norms surrounding police accountability in Connecticut. These include:

- forbidding quotas in pedestrian citations,

- the tightening of rules surrounding use of force (chokeholds are only permissible when employing deadly force, and the threat of serious physical injury is no longer justification for use of deadly force),

- the power for any town to create a civilian review board if it chooses,

- mandatory behavioral health assessments for officers,

- implicit bias training,

- requirements for racial diversity recruitment efforts, and

- the creation of an Office of the Inspector General to investigate cases of deadly force.

One of the most potentially effective aspects of the legislation is § 41 Civil Cause of Action Against Police Officers who Deprive Individuals of Certain Rights, which is intended to enable citizens to sue police officers in civil suits more easily if their rights have been violated. The section provides a new state/civil cause of action to sue officers under equal protection without the benefit of governmental immunity—the state law term for federal qualified immunity—and thereby drastically reducing a barrier to proceeding with a legal response to allegations of police mis/conduct..132 Qualified immunity was created by the Supreme Court in 1967 in order to protect officers who mistakenly believed, in “good faith,” that an arrest was covered by the law.133 However, it has since come to provide extensive protections for police, even when there is unequivocal evidence of acting in bad faith, as long as the officer did not violate “clearly established law.” This standard becomes essentially impossible to meet in practice. Indeed, qualified immunity holds that an officer cannot be held responsible for mis/conduct that has not been previously held unconstitutional under the same conditions, creating an arbitrary differentiation between legitimate and illegitimate behavior which is unrelated to actual events. UCLA Law professor Joanna Schwartz provides an illuminating example in Shielded: How the Police Became Untouchable:

State representative Raghib Allie-Brennan commented on the meaning of curbing qualified immunity after voting in favor to pass the act: “Establishing the power of accountability, which all of us are otherwise subject to and the existence of consequences for egregiously bad behavior, is critical to repairing the bond of trust between law enforcement and our communities.”135 Although the act prevents an officer from receiving immunity for an abuse of power conducted under bad faith, the Connecticut ACLU asserts this reform measure is limited in scope because officers still have the privilege of immunity if they have “objectively good faith belief” that they did not break any law.136 This standard provides wide latitude in the courtroom as the judicial system continues to side with what is perceived as the front lines of maintaining law and order. The efficacy of this provision, then, is debatable, although it can be considered to be a beginning. Any checks on qualified immunity, which represents a major “shield” against accountability, moves the situation in a more equitable and consistent direction of the consideration of all perspectives.

Notes

124. “An Ordinance Amending Article V, Division 5, Section 2-196 of the Hartford Municipal Code,” (Resolution of

the Court of Common Council, Hartford, 2020) 45-53.

125. “Resolution” (Resolution of the Court of Common Council, Hartford, 2020), 60. Link opens PDF.

126. Rondinone, “Cases Still Unresolved.”

126 Rondinone, “Cases Still Unresolved.”

127. “ACLU-CT Reacts to legislature’s Passage of Police Accountability Bill,” ACLU Connecticut, July 29, 2020. url.

128. Court of Common Council, “Majority Report of the Special Council Committee de Investigation of Shootings

and of Existing Police Guidelines for Use of Force in Connection Therewith” (Hartford, CT, 1970), 4-5. Held by the

Hartford History Center

129. Lum, C., et al, “Research on body-worn cameras: What we know, what we need to know,” Criminology & Public

Policy, March 24, 2019, 93. Cited in “Research on Body-Worn Cameras and Law Enforcement,” January 7, 2022,

National Institute of Justice.

130. Kim Healy, “Concerned About the Consequences of the New Police Accountability Law,” CT Mirror, September

25, 2020. Online.

131. “HB 6004: What Connecticut Officers Need to Know…” DLG Learning Center, Daigle Law Group, August 3,

2020, url.

132. HB 6004 An Act Concerning Police Accountability, LCO #3700, (2020) 63-64. PDF.

133. Joanna Schwartz, Shielded: How Police Became Untouchable (New York City: Viking, 2023), 74.

134. Ibid, 76

135. Raghib Allie-Brennan, “House Acts on Passes Police Accountability Legislation [sic.],” Connecticut House

Democrats, July 24, 2020

136. “ACLU-CT Position and Analysis of House-Passed Version of LCO #3700, an Act Concerning Police

Accountability,” ACLU Connecticut, July 24, 2020, url