1999

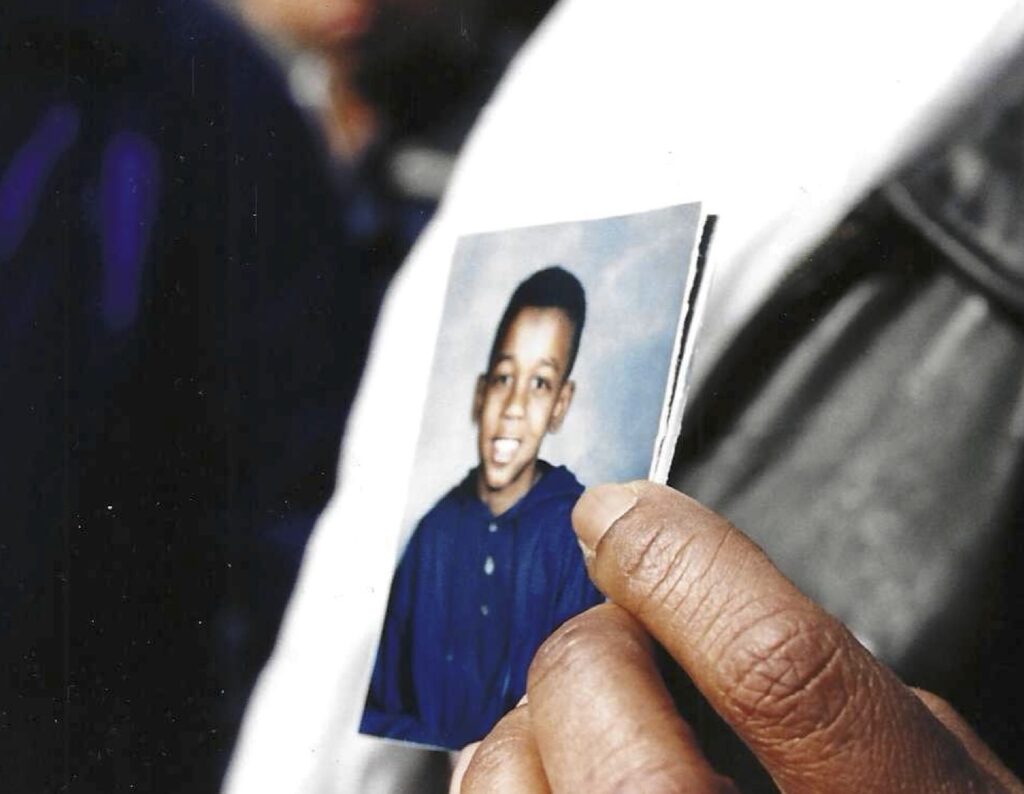

The shooting is, like so many, an example of fear-based policing with grave consequences. After a 911 call reports an attempted robbery and assault, Officer Allan pursues Salmon and three other boys driving in a white cadillac. When cornered by Allan’s police car in an alley, they abandon the car on foot in an attempt to escape. Allan later claims that he ordered Salmon to stop running and saw him reaching for a weapon, so he fired a single shot into Salmon’s back, killing him. Salmon is found with no weapon, and witness accounts report that Salmon was surrendering with his hands up when he was shot. Officer Allan had been “rebuked by his sergeant and lieutenant for unnecessarily displaying his service gun on calls” the year prior.61 The shooting occurs in an abandoned lot on Enfield street in the North End, the same street Salmon grew up on, and where he would often hang out with friends.

As was the case with Cintron, where Maria Cintron sought protection from the police for her son, the circumstances surrounding Salmon’s death call into question not only incidents of over-policing but under-policing as well. The day after the shooting, Salmon’s grandmother Norma Watts, with whom he was living, tells the Hartford Inquirer: “We are going to seek justice. I called the police two weeks ago to report that my grandson had ran away and never heard from them.”62 The presupposition that the child represents the prototypical object of police protection has not been a courtesy automatically extended to Black children. In the case of Salmon, rather than being a child in need of protection, he quickly became the embodiment of the threat against which society must be defended. In a moment, Salmon’s identity is relegated to the faceless, ageless label of the ‘suspect’.

On the scales of U.S. jurisprudence, being poor and Black often forecloses the assumption of care that is instinctively granted to supposedly innocent minors (and others) whose guilt is presumed. Consequently, such attitudes and structures radically reshape the experience of childhood for young Blacks, boys and increasingly girls, who are often treated by the courts as full-fledged adults.63 Indeed, Salmon had already had substantial interaction with law enforcement, having been placed under house arrest the previous December due to various incidents including carrying a concealed BB gun and was on probation at the time of his tragic death.64 Had he survived the night of April 13, he would have faced further justice involvement due to probation violation among other potential charges, and would have likely received very little sympathy from the same authorities who were compelled publicly to mourn his killing.

The day after the tragedy, Chief Joseph Croughwell organizes a major investigation and calls in Dr. Henry Lee, Connecticut’s public safety commissioner and leading forensic scientist, to analyze the shooting scene.65 Lee had worked on many notable cases including the O.J. Simpson and JonBenét Ramsey trials, and would later perform forensics on the 9/11 investigation and the attempted assassination of Taiwanese President Chen Shui-Bian. Croughwell’s decision to bring in this major figure marks the unusually intense attention he gives to the Salmon investigation, likely intended to show the North End that the HPD is sensitive to their outrage. Many press conferences are held over the coming days, including one organized by the HPD Guardians, who have a history of condemning racialized violence among their own department. Members of the media hear from police officials and members of Salmon’s family, such as his former foster mother Teri Morrison and his siblings, Michelle Salmon and Mark Barrow. His funeral is held a week after his death. “I don’t want to come here no more,” Salmon’s friend Cynphanie Wiggins told a reporter for the Hartford Courant, who interviewed him at the cemetery. “I don’t want to lose any more friends.” 66

In July, various civic and religious leaders come together to pursue “Justice for Aquan” through Cintron, which had been relatively inactive for many years. A press conference is held to announce their plans. Attorney Joseph Moniz, the lawyer responsible for investigating the consent decree’s potential, says “the city had already agreed to have a higher standard of police protection, and they have failed drastically in certain areas.” Moniz would later have a major role in litigating Cintron alongside Attorney Schulman. Also in attendance is Carmen Rodriguez, executive director of La Casa de Puerto Rico, who would also become a major player in the consent decree’s future. Offering words to a sentiment surely felt by many in the room, Minister Cornell Lewis remarks, “there is nothing more powerful than an idea whose time has come.”67 Indeed, as Cintron crystallizes as a viable path towards pursuing police accountability, Lewis’s words gesture to the potential fortuitously left behind by the judiciary thirty years after the suit was initiated. Cintron, long forgotten, is a door already open to those who look.

In June, Chief Croughwell enters a period of medical leave, which would lead to his permanent retirement just a couple months later. Assistant Chief Deborah Barrows, the highest-ranking Black person in the HPD and one of the highest-ranking female police officers in Connecticut, takes Croughwell’s place.68 She is promoted to interim chief in July, when Croughwell decides that his health has affected his ability to continue his tenure as chief. It is a volatile moment to enter the role, amid a dysfunctional department racked with scandal. Among the many pressures Barrows faces are demands from community leaders to revive the consent decree in response to Salmon’s shooting. They ask that, to comply with Cintron, Barrows re-establish the Firearms Discharge Board of Inquiry (FDBI); prevent officers from using mace and other chemical weapons for crowd control; conduct sensitivity training and code of conduct training; and increase routine training for veteran officers. These issues are not all directly tied to the shooting, but are occasioned by the momentum it has brought to the wider demands of the consent decree.69

The HPD is under scrutiny from within the city administration at this time, as well. On April 12, just one day before Salmon would be fatally shot, city council names a “looming and lingering crisis in the police department” which requires outside attention. The City commissions a management study of the HPD from Carroll Buracker & Associates, a prestigious Washington, DC-based consultancy firm.70 The researchers conduct many interviews with staff, perform onsite observation of the department’s daily functioning, and consult a vast amount of data, literature, and comparative evaluations with similar departments. Their study concludes with offering more than 150 recommendations for change within the HPD. Overall, Buracker & Associates find that the HPD is deeply disorganized and operates with poor efficiency, wasting taxpayer money without providing effective public safety for Hartford residents. The study provides quotes from HPD officers who feel their own department is seriously flawed: “Discipline is virtually non-existent in this Department;” “Our hiring practices here are terrible;” “I haven’t been evaluated in over 12 years; I don’t know whether I’m doing a good job.” Of particular relevance to Cintron, the firm recommends an overhaul of its hiring and promotion process, as well as its citizen complaint procedure. The latter recommendation comes five years before the plaintiffs in Cintron would submit their motion for contempt concerning the complaint procedure’s dysfunction; clearly, the department already knows in 1999 that their policies are inadequate long before they will be forced to change them.71

Notes

61. Josh Kovner, “Family, Police Want Answers,” Hartford Courant, April 14, 1999. ProQuest.

62.“Hartford Questions Yesterday’s Police Shooting of 13-Year-Old Black Youth,” Hartford Inquirer, April 14, 1999.

63. Juveniles can be tried as adults in many cases: for violent offenses, if they have a prior criminal history, if they are resistant to rehabilitation, or if they have been tried as an adult for a previous crime regardless of the seriousness of the new one. “When Are Juveniles Charged As Adults?” Branstad & Olson Law Office, October 5, 2023. Online. Juvenile offenders are not protected once they enter the justice system; on any given day there are at least 4,500 children housed in adult jails and prisons, where they are at greater risk for sexual assault, abuse, and solitary confinement for “protective” purposes. “Children in Adult Prison,” Equal Justice Initiative, accessed January 21, 2025. Online.

64.Helen Ubinas, “Aquan Salmon’s Life of Contradictions: Why City Teen Died is not the Only Question,” Hartford Courant, April 28, 1999. ProQuest.

65. Ibid.

66. Helen Ubinas and Eric Weiss, “Teen’s Funeral Doesn’t Answer ‘Why?’ Hundreds Bid Farewell to Aquan Salmon,” Hartford Courant, April 21, 1999. ProQuest.

67. Marcus K. McGhee, “Community Leaders Unite to Address Alleged Civil Rights Violations,” Hartford Inquirer, July 14, 1999.

68. Josh Kovner and Helen Ubinas, “Acting City Police Chief Steps Into Swirls of Controversy For Now, Barrows Has The Force,” Hartford Courant, June 17, 1999, ProQuest.

69. Eric M. Weiss, Josh Kovner and Tina A. Brown, “Report Assails City Police Consultant Criticizes Training, Supervision,” Hartford Courant, October 12, 1999, ProQuest. See also Josh Kovner, “Federal Probe Sought of Shooting by Police,” Hartford Courant, September 14, 1999, ProQuest.

70. Weiss, Kovner and Brown, “Report Assails City Police Consultant Criticizes Training, Supervision.”

71. Caroll Buracker and Associates, Inc., “A Comprehensive Management Study of the Hartford Police Department,” Law Enforcement Management Consultants, October 19, 1999. Collection of Atty. Sydney Schulman.