1992

Mayor Carrie Saxon Perry continues to lead the push for further police scrutiny, a far cry from the early days of Cintron, when Hartford’s last conservative Mayor Ann Ucello consistently sided with the police department. Perry, the first Black woman to serve as Mayor of Hartford, was elected in 1987 with the support of North End residents.37 The day after the acquittal of the LAPD officers who beat Rodney King, Perry calls a press conference on the steps of city hall; “we will not tolerate that kind of behavior in Hartford. This is not Los Angeles.” Two weeks later, Chief Loranger seeks to prove her right by firing Officer Laureano over his videotaped assault from 1991. The HPD does not keep data tracking officer dismissals over use of force, but members of the department recall just two such cases over the past twenty years, and both officers were reinstated. Laureano would also be reinstated after four months’ absence, to the outrage of community members and Mayor Perry.38

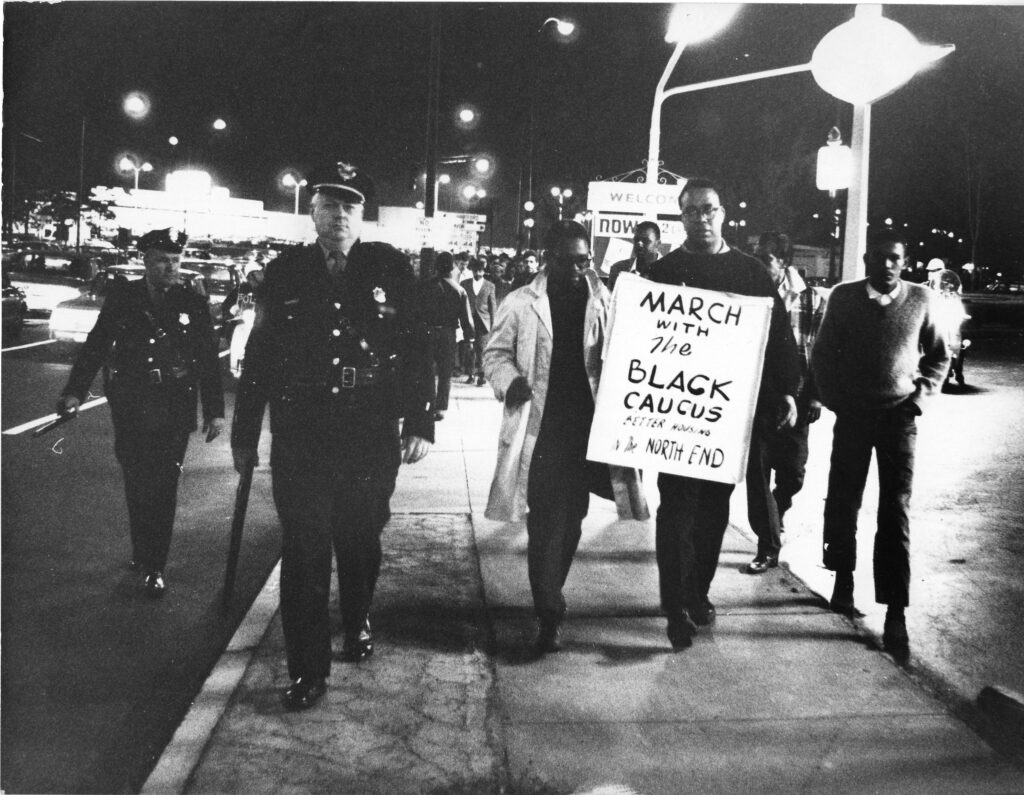

Mayor Perry’s conviction that “this is not Los Angeles” echoes long-standing narratives regarding the supposed standard of justice which distinguishes Connecticut, and the “North” more generally, from the states of injustice found in the rest of the country. A critique of an overzealous activist group published in the Hartford Times in 1963 praises Hartford’s civil rights record; “considering that we have probably the most advanced program in the United States, one can only wonder why these young people are wasting their time in Hartford when they could be on the real firing line in Mississippi or Alabama.”39 This supposed binary had its critics at the same time. The Hartford Times covered the activities of the Black Caucus in the late 1960s, a militant group organizing bold protests in Hartford, as pictured above. One article described the views of John Barber, spokesman for the organization: “As an example of ‘American cooperation,’ Barber said when arrested recently an Irish cop in Hartford kicked him, while an Italian cop held him. And this was in Hartford, he added, not Natchez, Miss.”40 The Hartford Star, the city’s foremost Black newspaper for much of the twentieth century, printed several articles complicating the North’s progressivism in the 1970s, during the start of Cintron. One piece reports that Black teachers are less discriminated against in the South than in the North, East or West.41 Another, titled “The Agony of: Northern Integration,” reads: “By now it should be obvious that racial prejudice and, more important, the social and economic conditions which pit white working people against the black poor, are national phenomena.”42 The persistent belief in Northern racial exceptionalism, despite abundant evidence to the contrary, represents a profound contradiction of liberalism. Even while pushing for police accountability, Mayor Perry downplays the prevalence of structural violence in Hartford by labeling it “not Los Angeles,” or, not a place with routine and deep-rooted racism.

In June, Officer Sergio Inho—a popular member of the force—is arrested for second-degree assault after beating a citizen the previous year. The victim, Edwin Cruz, required 100 stitches on his head for the gash given him by Inho. Within the context of public scrutiny the HPD felt starting in 1991, and the pressure for reform from the Mayor’s office, many officers think that these punitive measures taken against two individual officers are politically motivated and that the city administration is targeting them. Over 100 officers go on strike for a few days following Inho’s arrest.43 A rally is held in support of Laureano and Inho, and officers travel from several Northeastern cities to show their support. Fundraisers are held at which roast pig is served; “Hey we have a sense of humor,” commented the police union president.44 Immediately after the strike ends, tensions escalate again when city council votes unanimously to instate a new version of the civilian review board to replace the current body.45 The revamped review board, which was one of Mayor Perry’s campaign promises, implements changes such as increasing the civilian reviewers to five, and expanding the scope of cases from selectively excessive force to any complaints against police. The new review board faces serious roadblocks and does not hold a single meeting in 1992.46

Notes

37. Marla Romash, “Perry Dances in Victory After Steele Concedes,” Hartford Courant, November 4, 1987, ProQuest.

38. Andrew Julien, “Fired Officer May Win Reinstatement,” Hartford Courant, June 1, 1992, ProQuest. See also Blanca M. Quintanilla, “Chief Reinstates Officer Fired For Hitting Student,” Hartford Courant, September 29, 1992, ProQuest.

39. “NECAP Is Fouling Other Programs,” Hartford Times, August 20, 1963.

40. “Breaking Glass is Crying Barber Tells ‘TAN’,” Hartford Times, October 5, 1967.

41. Bill Reid, “Black Teachers Are Better Off In South,” Hartford Star, November 3, 1973.

42.“The Agony Of: Northern Integration,” Hartford Star, September 28, 1974.

43. Mike Swift, “Police Sick List Shrinks Slowly: ‘Blue Flu’ Action Keeps Strong Grip On Hartford Force,” Hartford Courant, June 7, 1992, ProQuest.

44. Stan Simpson, “Police Resides Differ On Review Board Plan,” Hartford Courant, June 16, 1992, ProQuest.

45. Andrew Julien, “In Hartford, Thin Blue Line Divides Police, Critics,” Hartford Courant, June 30, 1992, ProQuest.

46. Rachel Gottlieb, “Pressure Being Felt For Police Review Board,” Hartford Courant, May 31, 1993, ProQuest.