1970

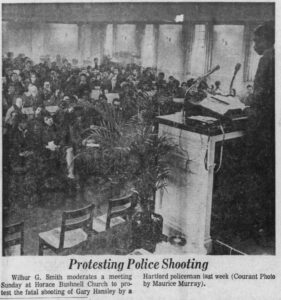

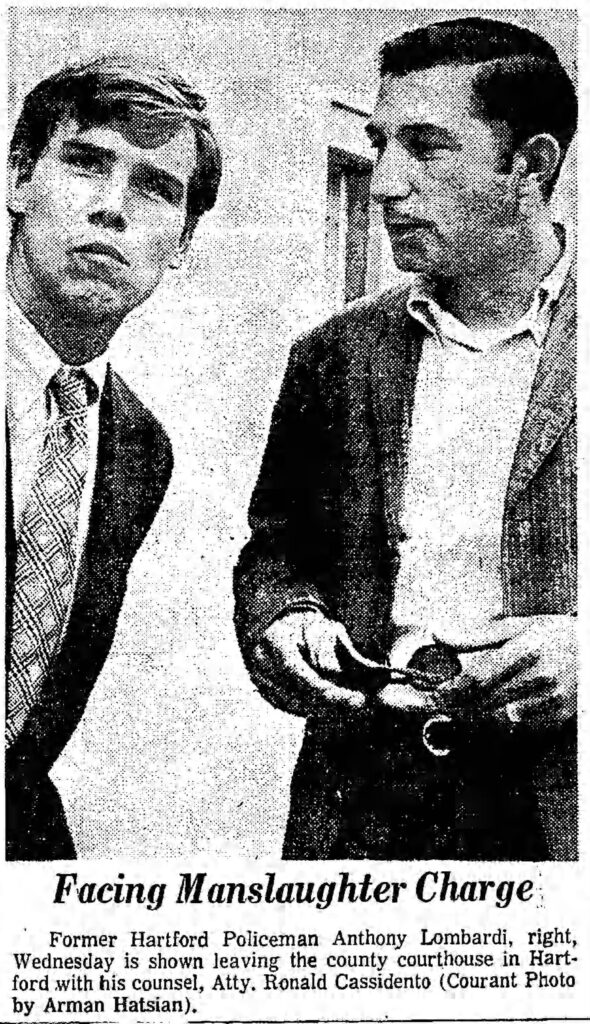

Residents of Hartford’s North End are galvanized into protest after another Black youth, Gary “Mike” Hansley, is shot and killed by HPD officer Elden Thibodeau, who faces no consequences. More police killings follow, including the unprompted shooting of Efrain Gonzalez during a protest, and the death of 19-year-old Abraham Rodriguez at the hands of officer Anthony Lombardi. Lombardi is convicted of manslaughter but later acquitted, further intensifying tensions between law enforcement and many Hartford residents. By mid-December 1970, Hartford police officers are responsible for 30 homicides, a record for the department. In response to increasing demands on the Hartford administration for police accountability, the city council establishes a three-person committee with subpoena powers tasked with investigating police use of deadly force and recommending changes to their guidelines. The implementation of the committee leads to a series of conflicts between city officials and the police union, which weakens the scope of the council inquiry. In the end, the committee votes to recommend no change in police guidelines, but the minority report submitted by councilmember Allyn Martin would later became a kind of manifesto encouraging efforts of police reform in Hartford up to the present day: “It would be well if Police and Community took cognizance of the fact that ‘policy for a gun shooting death is easily rewritten. Human life, once taken, lingers only in photographs, mementoes, epitaphs and newspaper accounts.’”5

Judge Blumenfeld, a Kennedy appointee with a fairly liberal record, denies the city’s motion to dismiss Cintron. Plaintiffs provide a list of seventy witnesses with personal experiences of police harassment or violence, fifty of whom submit written testimony to the court. The counsel moves ahead with discovery, requesting that Chief Vaughan provide records of all complaints filed for the past two years, all records concerning police interactions with witnesses from the past three years, various police policies including those concerning complaint procedures, the HPD’s manual, their training curriculum, and their collective bargaining agreement with the Hartford AFSCME Union.6 Appearing before the court, the defendants’ attorney Joseph Lorenzo describes the difficulty he has encountered while trying to produce the complaint records:

Mr. LORENZO: All right. Our records are going on a machine, but heretofore they have not been on tape and I don’t even know if these records are available. People are loathe to keep records where complaints are made to them about themselves. I don’t even know if they’re available and this is why I suggest that this may be premature. Let me inquire, let me pursue this.

THE COURT [Judge Blumenfeld]: Well, there is nothing premature about it, Mr. Lorenzo. The case has been hanging for quite a while and I would be loathe to be put in a position of appointing a Master in order to make a search of your records. I can understand the reluctance to keep records of complaints made against the organization, but it doesn’t seem conceivable to me that they’re thrown into the wastebasket.

Mr. LORENZO: I don’t know, your honor, and we can make available what we have. What can I say?7

Lorenzo requests a five or six months’ extension to gather the complaints, and Judge Blumenfeld grants thirty days, estimating that there are six or seven complaints filed a month. In reality, that number is about thirty seven per month, and the department is unable to produce them in time, or simply does not have them.8 The preceding exchange casually sums up the impossibility of accountability within the HPD in 1970: “people are loath to keep records where complaints are made to them about themselves.” The issue of complaint records is a kind of metonymy or originating symbol representing the nature of police power, troubling the Plaintiffs even before the consent decree was enacted. It would remain central to the case’s litigation throughout the decades to come.

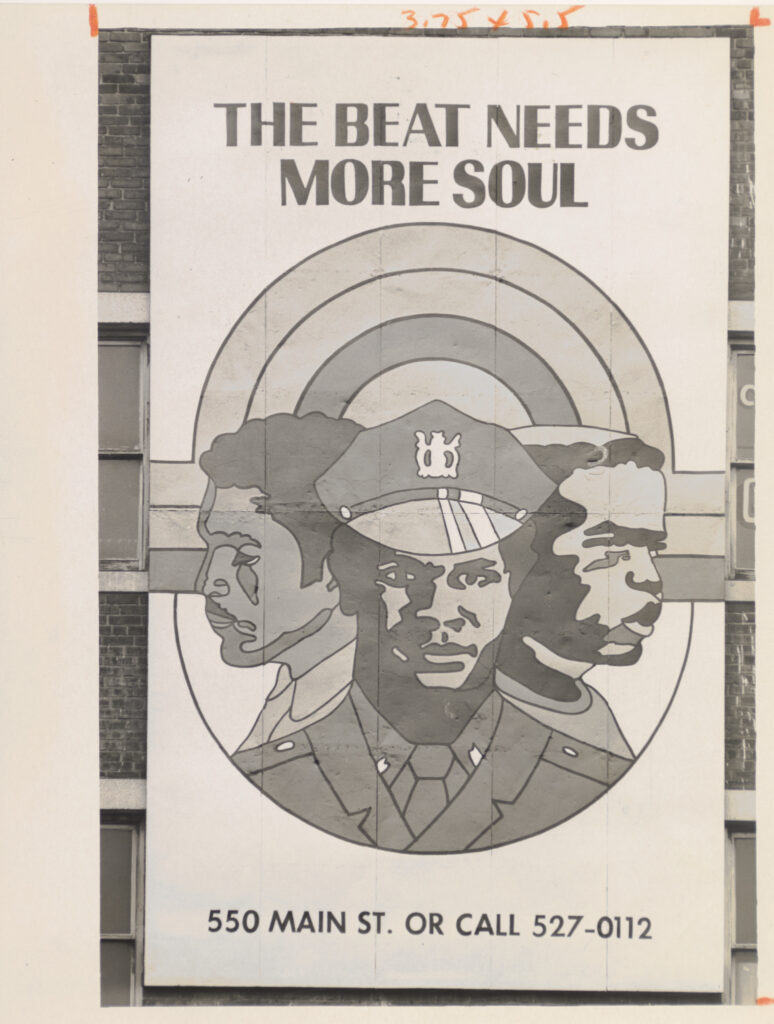

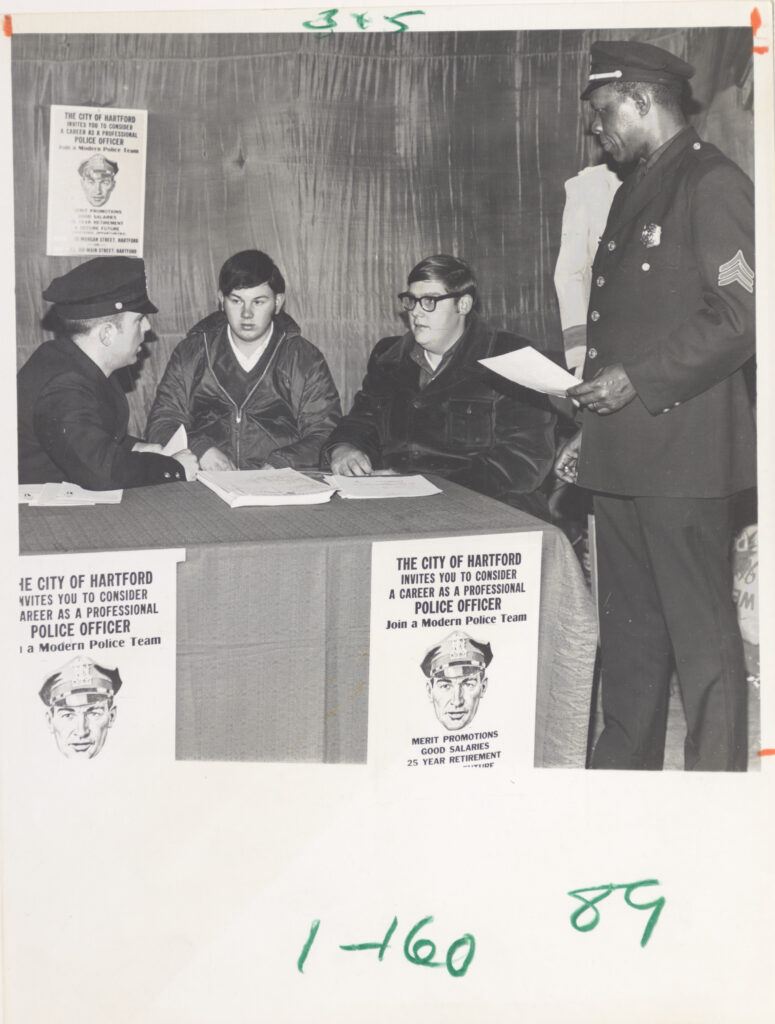

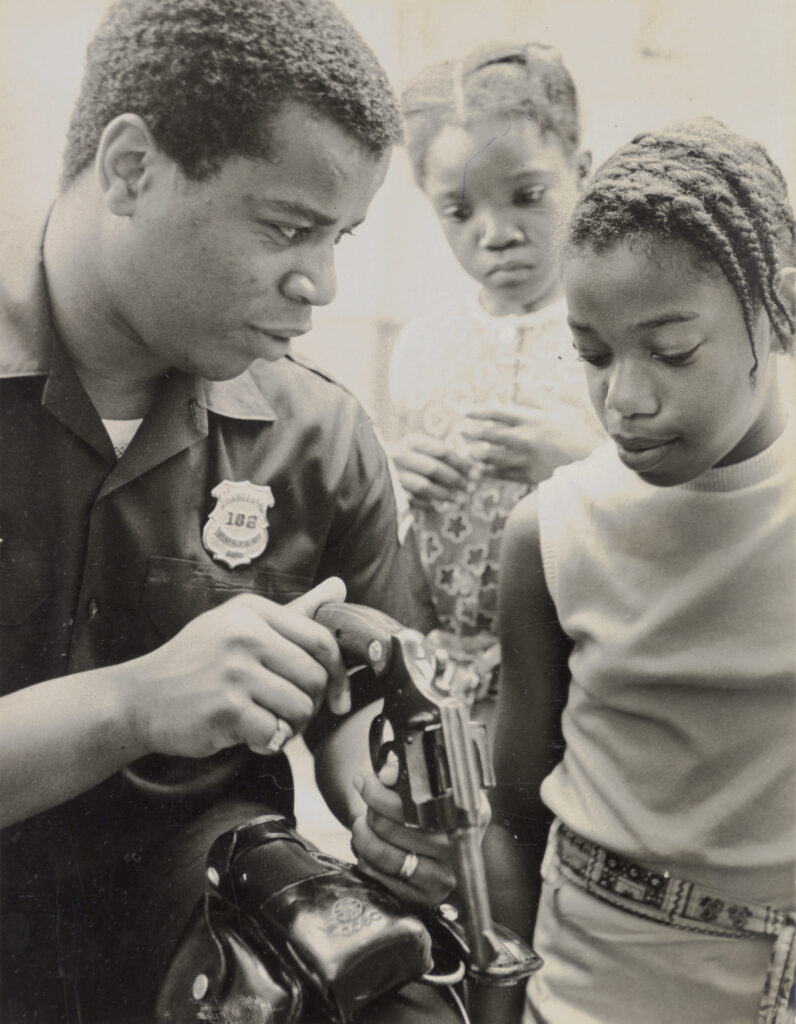

Together with the issue of reform, racial diversity within police departments remains a major topic of discussion in Hartford, and continues to be until the present. Many residents hope that the presence of Black and Latino police officers will result in the use of less force and fewer deaths, as their presence within the department would ideally diminish the culture of racism. This vision hinges on the paradoxical position in which these officers find themselves; having to identify with both the militaristic arm of state power, as well as with the communities most harmed by policing.

This topic emerges in the pages of the Hartford Star, the city’s foremost Black newspaper, during the initial filing of Cintron. Carl D. Smith’s opinion essay “Black Police and the Community,” (1970) offers a nuanced view of the contradiction that remains a crucial sticking point in conversations about police reform. Smith points toward the increasing racial pride among many Black officers, which on one hand, offers a gesture of hope rooted in the growing awareness of mutual respect within departments. Yet, on the other hand, most of the article remains critical of this possibility, and notes the tendency for all officers to abuse their power. Smith writes that the Black officer is viciously disrespected as “the ghetto’s oppressor-in-residence,” and that “in part compensation for this loss of prestige and respect, many black lawmen have used the ‘strong arm of the law’ to restore the respect and have redirected the symbolic prestige represented by the uniform to themselves.”9 Despite that such a critique has long been raised, racial diversity has remained a consistent aspiration within visions for police reform, being coterminous with the arc of history of Cintron.

Notes

5. Honorable Court of Common Council, Special Council Committee, Minority Report Received from Councilman

Martin, a Member of the Special Council Committee, November 2, 1970, Page 9

6. Motion for Order Compelling Discovery, Cintron, et al v. Vaughn, et al, 3:69-cv-13578-KAD (D. Conn. September

11, 1970).

7. Transcript of Counsels’ Appearance Before the Court, Cintron, et al v. Vaughn, et al, 3:69-cv-13578-KAD (D.

Conn. October 13, 1970).

8. Motion to Enlarge Time, Cintron, et al v. Vaughn, et al, 3:69-cv-13578-KAD (D. Conn. November 20, 1970).

9. Carl D. Smith, “Black Police and the Community,” Hartford Star, June 20, 1970.