Conclusion: The Dual Legacy of Cintron

Ultimately, the consent decree was terminated not because the HPD had fixed its systemic problems, but rather on the technical grounds that there was no proof it had directly failed to comply with the 1973 or 2010 agreements. The language in these motions was often aspirational and usually quite imprecise, which led to them holding little standing in the courtroom. The story of Cintron v. Vaughn searches for a path between the perceived potential and evident limitations of judicial police reform. Often, “justice” does not represent the totality of the facts, or the feelings of the public, or even the volume of harm caused, but rather a game played—earnestly—between narrow readings.

In her final order regarding the dissolution of Cintron, Judge Dooley affirmed the need for reform in the HPD, but felt that judicial oversight was no longer the appropriate arena in which to do so: “The next step in Plaintiffs’ continuing important and commendable efforts to promote diversity in the Hartford Police Department lies not with this Court, but with the police department itself, the City of Hartford, and the greater Hartford community.”162 What does this step look like? After city council resolved that the HPD institute its own policies to align with Cintron and that they publicize their progress, Council Majority Leader Thomas “TJ” Clarke II told the Hartford Courant that transparency was at the center of the resolution: “I think it’s important for people to know about their police force. What are the demographics of the incoming recruiting class? Or from an overall perspective, what is the composition of the Hartford Police Department? These statistics will now be accessible to everyone.”163 Is the force’s racial diversity—a concern which took the forefront in Cintron’s last leg of litigation, in Judge Dooley’s decision, as well as in the city council’s response—a promising avenue for decreasing discrimination in policing and advancing public safety? A full engagement with that question is beyond the scope of this project, but the history and discourse surrounding Black police officers in Hartford and beyond suggests that racial diversity is a complex and uneasy direction for reform.

Using James Forman Jr.’s Locking Up Our Own as a point of departure, Devon Carbado and L. Song Richardson assess the complexities and contradictions of using racial diversity as a strategy to effect police reform, a discussion that provides insight into the situation of Deborah Barrows noted previously in 2000. Carbado and Richardson employ sociological, psychological and legal sources to explain the reasons that some Black police officers also exhibit racial bias and use excessive force against Black civilians, in fact, just as frequently as White officers do. Some of the causal factors they suggest, include: Black officers may simply have the same racial biases as White officers; they may experience “self-threats” or psychological threats to their selfhood which are then reaffirmed through demonstrations of authority; they may feel significant pressure to fit into their department’s culture; and finally, the structure and legal backdrop behind policing puts serious pressure on officers to overpolice poor areas predominantly inhabited by Blacks and Latinos.164 Currently, many police departments are significantly diverse; some, such as the LAPD, have a non-White majority of officers. Yet, this “progress” has not altered the structure of police power. Perhaps, this should serve to initiate a new set of questions and objectives beyond diversifying law enforcement.

Carbado and Richardson point to several recursive cycles which exacerbate overpolicing in Black communities, one of which is associated with “stereotype threat.” This psychological phenomenon, initially defined by Claude M. Steele, “refers to the anxiety that occurs when people are concerned about confirming a negative stereotype about a social group they value and to which they belong.”165 Ironically and tragically, when police officers are worried about people assuming they have racial biases based on police stereotypes, they may exhibit an increased propensity toward violence because they fear their legitimacy is threatened. Often, the officer’s authority is reasserted through force directed towards Black civilians, who have represented and imagined to be the prototypes and embodiment of criminality. This theory provides an insight into the deeply ingrained problems within police departments such as the HPD, which have been attempting to reckon with discriminatory reputations for decades. Despite the warnings which have long been raised by victims of over- and under-policing and astute commentators such as Carl D. Smith, whose article “Black Police and the Community” was published in the Hartford Star in 1970, racial diversity has remained a stable and unwavering aspiration within mainstream progressive visions of police reform. Carbado and Richardson conclude by asserting that “whether or not police officers are policing their own, if the broader structural forces we have discussed remain the same, the racial dimensions of policing with which the nation continues to grapple are likely to persist.”166

If not racial diversity, what are other “next steps” for the HPD? One former officer feels that what Cintron lacked in scope was taken up by 2020’s Police Accountability Act. Perhaps the legislature, in its more direct relationship with the populace, is a better arena for these kinds of negotiations but time will tell. Outside the sphere of government, the media has been a moderately effective conduit for change, as seen in the department’s immediate response to the Hartford Courant’s 1992 investigation into police use of force case tracking. However, the media’s potential is quite limited to those few cases which become spectacularized, in part disguising their normality and providing the illusion of easy progress. Such raises the question as to whether this kind of publicized change may actually slow real progress, since it is easier to excommunicate the “bad apples” like Derek Chauvin than it is to address systemic issues which guarantee the continuance of racialized violence and discrimination under the color of law.

Judge Dooley’s decision to terminate the decree after fifty years caused great concern among community organizers and politicians in the city. Betts remarked that “We are deeply concerned that this dissolution of the consent decree will go in a step backwards for the city of Hartford and its residents.” and this was especially the case for “our Black and brown community members who have historically been targeted by discriminatory policing practices.”167 In keeping with the case’s inception, critiques of its dissolution are concerned with both over- and under-policing. While Betts advocated for judicial oversight to curb such issues as excessive force and discriminatory traffic stops, state NAACP leader Scot Esdaile pointed to the high rate of violent crime in Hartford, which saw “39 murders last year [2022]. Violence is out of control in our city, and this particular decree should not be sunsetted.”168 These responses to Cintron’s dissolution are not always directly tied to its actual functioning; in the public imagination, the consent decree wielded more power than it ever did in practice, suggesting that calls for racial equity represent a threat to the mainstream social order.

From 1973, Cintron was a statement of intention more than a method towards realizing significant change, and inertia tends to reign in matters of bureaucracy. City councilmember Joshua Michtom has perceptively noted: “[The] HPD remains allergic to transparency, reluctant to impose lasting consequences on officers who misbehave, and unrepresentative of the city it serves. More oversight can’t hurt. That said, half a century of federal oversight hasn’t fixed those problems, so maybe the lesson here is that federal oversight actually doesn’t help that much.” He further emphasized the wider social context in which policing functions: “In the end, I wish the city were more focused on making residents safer by giving them economic opportunities and improving their quality of life, instead of pouring more and more money into the police department. Ultimately a federal judge can’t make that happen.”169 To be sure, important tangible progress was made with regard to the civilian complaint procedure, the FDBI, and the investigations conducted into officer-involved shootings. But ultimately, Cintron’s value may have lied most in the space it opened for imagining alternative futures. The consent decree provided a field of potential in which competing visions of policing could be negotiated, albeit via the formal demands of the justice system. Even when faced with barriers to progress and resistance from the HPD, Cintron signified hope. The case empowered community members to demand checks on officers’ use of firearms, to ensure adequate investigations when members of the community were harmed or killed, and to name the language of harassment used by police as a mode of racial violence. The heart of the consent decree’s saga was its role as a vessel for public outrage and grief when community leaders exhumed it in response to the 1999 murder of Aquan Salmon. Its importance in that moment could not have been predicted when the case was filed thirty years prior, in 1969. Cintron was a potent acknowledgement, consistently re-affirmed, that the police are not infallible, that claims against them are legitimate, and that power is worth confronting.

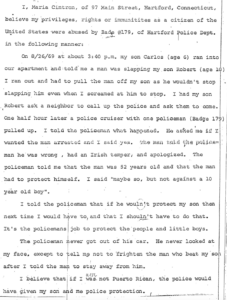

Cintron landed far from the place where it began. Procedural reforms, such as racially diverse hiring, that would later take on primary importance, were not at the center of the plaintiffs’ complaint in 1969 when it was first filed. That document speaks to a more existential claim: that being denied protection and being harmed by agents of “public safety” is indicative of exclusion from the state’s vision of the public, which is to say, excluded from the category of the human. Maria Cintron’s witness statement, included in full below, describes that exclusion as it was expressed to her in the case’s founding incident: “The policeman never got out of his car. He never looked at my face, except to tell me not to frighten the man who beat my son after I told the man to stay away from him.” These experiences of dehumanization are fundamentally deeper than the proposed bureaucratic reforms of diversifying a homogenous police department, or firing one “bad apple” officer. The wide acceptance of such disrespect, reserved for those regarded as less than fully human, speaks to the integral fabric that binds the system of state control with dehumanization; one is intrinsically connected to, and informed by the other. The power of this statement is not measured by the changes it brought about; indeed, its power is evidenced by the lack of such change. Despite affecting the HPD’s activities for fifty years, Cintron’s foundational claims of dehumanization were too radical to be adequately addressed within the pillars of the same society which caused them. The plaintiffs in Cintron over its half-century tenure exhibited the precious bravery that has compelled every act of resistance across history, few of which have been heard, fewer of which have been heeded. The gap between the radical assertion and the clumsy machinery of its reception must constantly be tested if change is to occur. It is in this function that Cintron’s legacy continues to shine.

Notes

162. Order Denying Motions for Reconsideration, 6.

163. Stephen Underwood, “City council votes to require accountability, transparency from Hartford police force,” Hartford Courant, September 28, 2023. ProQuest.

164. Devon Carbado and L. Song Richardson, “The Black Police: Policing Our Own,” Harvard Law Review 131, no. 7 (2018) 1989-2023.

165. Ibid., 2000.

166. Ibid., 2025.

167. Deidre Montague, “NAACP Branches Dislike Ending of Hartford Police Consent Decree” Hartford Courant, April 20, 2023. ProQuest.

168. Ibid.

169. Deidre Montague, “Judge Ends Landmark Half-Century Old Hartford Police Consent Decree,” Hartford Courant, April 18, 2023. Courant online.