2000

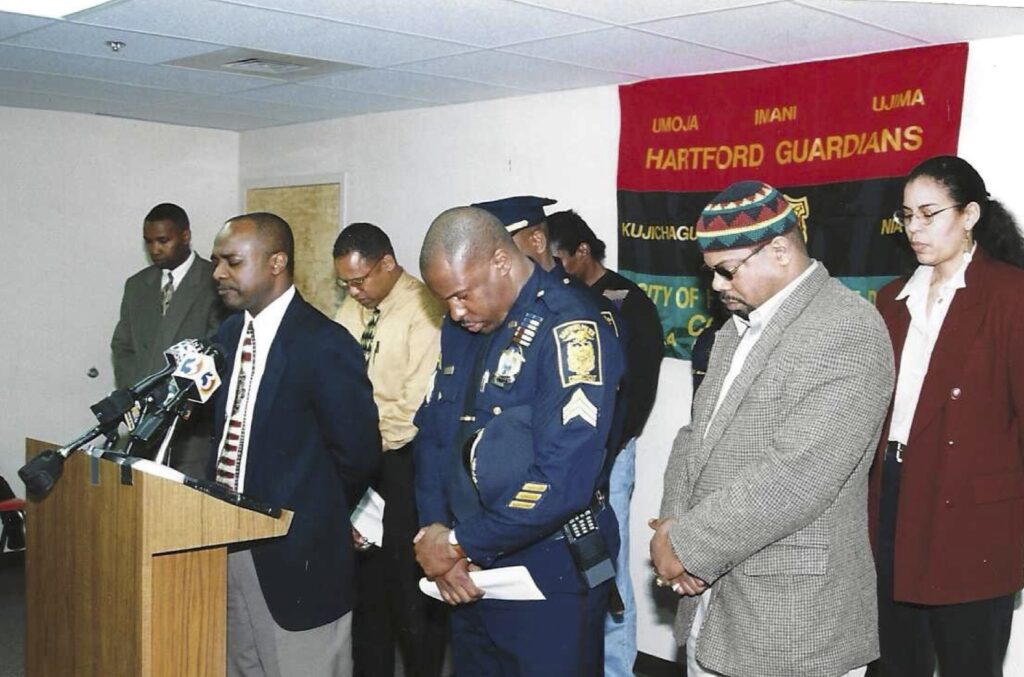

The killing of Aquan Salmon shakes the Hartford community to its core, underscoring a deep and omnipresent fear of anti-Black violence perpetrated by the Hartford Police Department. The media coverage of the incident follows the familiar pattern, the tragic killing obscured by the narrative of Salmon’s perceived criminality as justification. The collaboration between community leaders initiated in 1999 proves fruitful, and the group—led by Carmen Rodriguez, Reverend James Walker, and Wadell Muhammad—pursues measures of accountability through the judicial system using Cintron, with a commitment to improving conditions of law enforcement which would prevent another such death. The city agrees to create a new nine-member Firearms Discharge Board of Inquiry (FDBI) with three civilian members, as well as a new police rule regarding the use of weapons; both of these policies, referred to as 1-21 and 1-22, are updated versions of stipulations included in 1973 in Cintron’s initial terms.72 State prosecutor Kevin Kane exonerates Officer Allan in February, and the HPD begins their own internal investigation shortly thereafter.73 As city officials ask for a thorough internal inquiry into the shooting, the HPD proves resistant to increasing demands for reform and oversight. The HPD review panel assigned to the shooting is suspended mid-meeting after residents raise concerns that it violates the new policy.74 The panel was composed of officers alone, rather than the civilian-police FDBI body, which had recently agreed upon under Cintron negotiations.

On March first, after pushback from the City Council, both parties to the renewed Cintron litigation agree that the court would appoint an independent monitor of compliance, or “Special Master.” Judge Ellen Bree Burns is now presiding over the case, a Jimmy Carter appointee with a progressive record who had been the first woman to preside in a Connecticut federal court.75 Judge Burns names attorney Richard A. Bieder to the position. Bieder is a widely respected Connecticut lawyer with a robust civil rights record who often works pro bono. As stipulated, the Special Master “shall have the power to make decisions on disputes between the parties regarding the enforcement of the Consent Decree . . . shall have the duty to conduct hearings to determine whether or not the Consent Decree has been violated . . . [and] shall have the responsibility and duty to oversee all aspects of the Consent Decree.”76 Shortly after Bieder is named to the role, he rules that Allan’s use of force was within his authority as a police officer since he believed his life had been in danger. Bieder regards Salmon’s death, resulting from being shot in the back, as tragic but nonetheless justified.

In May, Deputy Chief Robert Casati faces disciplinary proceedings for the discriminatory language he allegedly used in 1997. Casati’s behavior is found to be within reason by City Council Arbitrator Albert G. Murphy, who considers it a fair consequence of the grueling work of a police officer: “Police officers are people who carry guns to work, who make their living going up dark alleys in dark hours for rapists, murders, robbers and the like. They are not necessarily candidates for garden parties … When a person faces the possibility of injury or death on every eight-hour shift, he or she tends to lose track of social niceties.”77 In his decision to reinstate Casati as deputy chief, Murphy writes that an officer’s language might reflect the challenging and violent world that he experiences each day, and therefore Casati’s racial epithets should not be taken too seriously. Murphy’s decision stands in tension with and minimizes the effects of disrespectful and derogatory language ascribed by the plaintiffs in Cintron. On one hand, the inclusion of “Trigger Words” (see 1997) in the consent decree acknowledges the role language plays in police-community relations, a response to the plaintiffs’ claim that racial slurs are part of the regime of humiliation the HPD exercises against the city’s Black and Puerto Rican citizens. However, on the other hand, the consent decree does not fully acknowledge that such language is related to the wider social context of, in contemporary parlance, anti-Black and Brown racism, implying that such statements are harmful only when overheard by citizens. The recognition that the internal culture of the police force directly relates to how law enforcement interacts with the public might have been too contentious for the consent decree to assert. Consequently, this position conforms to Murphy’s condoning the “blue humor” or racial epithets spoken by police officers and indeed his decision reaffirms the logic of violent language and violent behavior as intrinsic to the conduct of policing.

Acting Police Chief Deborah Barrows is ousted in July, amid claims of her inability to investigate the Salmon shooting. Council members and activists find Barrows’s actions during Allan’s hearing in violation of city council rules, specifically the new FDBI procedure recently signed that updated the review protocol included in Cintron. Barrows’s actions are perceived as contravening direct orders and therefore indicative of insubordination, quickly shattering her professional identity.78

Particularly significant about Barrows’s position are the diverging expectations set forth for her as a Black woman from Hartford’s North End leading the city’s police department. During her time in the force, Barrows is expected to appease the community that looked to her for advocacy of their concerns, and at the same time, to uphold the blue wall of silence climate. The needs of these constituencies are clearly in opposition between those who police and those being policed. Cindy Austin reports in the Hartford Courant on the immediate aftermath of Barrows’s demotion, describing the complicated and conflicting feelings that many holding expectations of racial justice expected of her tenure as police chief. Austin writes that “Barrows’ high-profile status comforted the city’s minority population and assured them that the department would do its best to get down to the bare bones of the Salmon investigation. They were depending on her to make it happen. To them, she was more than a figurehead. She had become the promise of a new beginning for a city that was seemingly being rent away from them. Barrows was the one with the mantle, the one who would usher in the vision for that other Hartford.”79 Barrows was well regarded by many in the Black community, such as by Aquan Salmon’s grandmother Norma Watts who described her as “blessed,” commenting that “she’s different from the rest. I appreciate her for that. She shouldn’t have to do the department’s dirty work. When this happened she wasn’t in charge. It’s an unfair burden.”80 Watts’s assessment and Austin’s observation speak to the difficulty Barrows faced being placed at the head of a department with many challenges. Barrows joined the force in 1973 and was welcomed with the signing of Cintron. When she was appointed acting chief in 1999, the HPD had seen over twenty officers arrested for crimes conducted on duty. Moreover, the department’s internal functions were in disarray and morale was low. The Buracker report, which exposed these and other deep-seated structural problems within the HPD in its 400-plus page report, was released just a few months into Barrows’s tenure. Although she possessed little control over the department’s direction, she was nonetheless deemed responsible for the questionable, if not illegal, behavior of some of its members.

These expectations placed on Barrows failed to account for the contradictory obligations of a Black police officer, discussed by Card. D. Smith thirty years prior in the Hartford Star article “Black Community and the Police” (see above, 1970). Smith acknowledges that “in many instances, the patrolmen want to better communicate with the ghetto, but find it difficult defining what they believe to be the conflicting demands of being a concerned black citizen and a police officer.”81 As analyzed by James Forman Jr. in his book Locking up Our Own: Crime and Punishment in Black America—a Pulitzer-winning study of the War on Crime as supported by Black leaders in Washington, DC—these “conflicting demands” will always result in upholding the systems granting those officers authority in the first place.82 Locking Up Our Own critically analyzes the position of Black police officers, judges, and politicians whose work actively maintains the system that continues to place a disproportionate number of Black people in prison. Forman argues that the individuals in these positions should not be expected to do anything more than the role they have taken on for themselves; if they have committed to upholding the police state, that is exactly what they will do, regardless of their race. Forman quotes James Baldwin’s claim that “the function of an urban police force was to keep the black man corralled,” deducing that Black officers, and those in similar positions of power, must not be expected to alter the nature of policing from its original function.83 The conflicting emotions held by both Black Hartford residents and activists fighting against racial violence speaks to two simultaneous truths—Black officers like Barrows will, despite their sensitivity and/or identification with Blacks, nonetheless continue to uphold police systems which disproportionality incarcerate Blacks, though they will oftentimes be scapegoated, disrespected and discarded when convenient for those in power.

Notes

72. Tina Brown, “Police Review of Shooting Stalled Legal Concerns Over Procedure Put Panel On Hold,” Hartford Courant, February 24, 2000, ProQuest

73. Eric. M Weiss and Josh Kovner, “Chiefs May Be Ousted City Leaders Vow to Solve Police, Fire Leadership

Problems,” Hartford Courant, February 19, 2000, ProQuest.

74. Brown, “Police Review of Shooting Stalled Legal Concerns Over Procedure Put Panel On Hold.”

75. Joseph P. Fried, “Ellen Bree Burns, Barrier-Breaking Connecticut Judge, Dies at 95,” New York Times, June 4,

2019. ProQuest.

76. Stipulation Re: Special Master, in Defendants’ Objection to Re-Appointment of Special Master for a Period of

Three Years, Cintron, et al v. Vaughn, et al, 3:69-cv-13578-KAD (D. Conn. May 5, 2004).

77. Brown, “Former Deputy Chief Reinstated an Arbitrator Has Ruled That Despite Allegations of ‘Obscene Gutter

Talk,’ the City Failed to Prove that Caption Robert J. Casati Created a Hostile Working Environment.”

78. Cindy Brown Austin, “Lament for Deborah Barrows,” Hartford Courant, August 13, 2000, ProQuest

79. Ibid

80. Tina Brown, “Aquan Salmon, Hartford’s Police and Deborah Barrows,” Hartford Courant, February 18, 2000,

ProQuest

81. Carl D. Smith, “Black Police and the Community,” Hartford Star, June 20, 1970.

82. James Forman Jr., Locking Up Our Own: Crime and Punishment in Black America (New York City: Farrar, Straus

and Giroux, 2017).

83. James Forman Jr., Locking Up Our Own: Crime and Punishment in Black America (New York City: Farrar, Straus

and Giroux, 2017).