1994

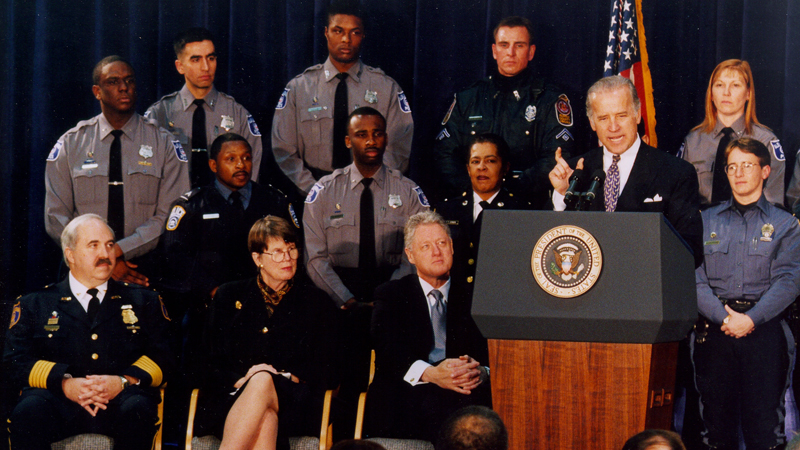

Section 14141 of the 1994 Crime Bill writes into federal law the jurisdiction of the Department of Justice to “commence a civil action against a police department that exhibits a ‘pattern or practice’ of violating citizens’ constitutional rights to obtain equitable or declaratory relief that will eliminate the practice.”47 This authorization by the DOJ sets precedent for what Hartford had uniquely experienced twenty years prior when Cintron was settled via a consent judgment. Following 1994, consent decrees begin emerging after prominent cases in which police use of violence is questioned. As a response to national outcry, typically after an unlawful murder at the hands of a police officer, many police departments are placed under judicial oversight. The post-1994 understanding of consent decrees has been illuminated following notable cases of police violence in recent years: The Louisville Police Department is placed under a consent decree (2024) following Breonna Taylor’s murder; in Baltimore after Freddie Gray’s murder (2017); in Ferguson after Michael Brown’s (2016); and in Minneapolis after George Floyd’s (2025).48 Cintron is especially notable considering that the historical accounts do not mention it. The Vera Institute considers the practice of consent decrees in law enforcement to have “originated in the 1994 Crime Bill—a law that fueled mass incarceration and expanded racial disparities in our legal system.”49 It is evident that Cintron is missing from the dominant historical record of national police-focused consent decrees, a discovery which positions this study as a unique effort to fill in this gap..

On a local scale, the HPD is placed under judicial scrutiny again, separate from the ongoing but inactive consent decree. Superior Court Judge Arthur Spada releases the results of an eighteen-month probe into corruption in the department. The report is scathing, naming forty unprofessional and criminal behaviors conducted by HPD employees on the job. Spada writes that the breakdown in discipline is due to the damaged authority of Hartford police chiefs, who have been overtaken by a disciplinary state appeals board which works slowly and gives lenient punishments for infractions.50 Officer Luis Ortiz, president of the Hartford Police Hispanic Officers Association, is concerned that half of the officers implicated are Latino. “For me as a Puerto Rican this is another kick in the face. It’s always Puerto Ricans. We really are the minority in the department, but yet we are always targeted in investigations.”51

Notes

47. Elliot Harvey Schatmeier, “Reforming Police Use-of-Force Practices: A Case Study of the Cincinnati Police”, Department, 46 Colum. J.L. & Soc. Probs, 2013, Page 539.

48. am McCann, “Everything You Need to Know About Consent Decrees,” The Vera Institute, August 30, 2023, Vera.

49. Ibid.

50. “Who Will Police The Police?” Hartford Courant, October 31, 1994, ProQuest. See also Maxine Bernstein, “Corruption Probe Raises Question Of Ethics, Community Policing,” Hartford Courant, October 31, 1994, ProQuest.

51. Maxine Berstein, “Grand Juror Finds Police Misconduct 5 Officers Charged With Theft, Perjury,” Hartford Courant, October 26, 1994, ProQuest.