1973

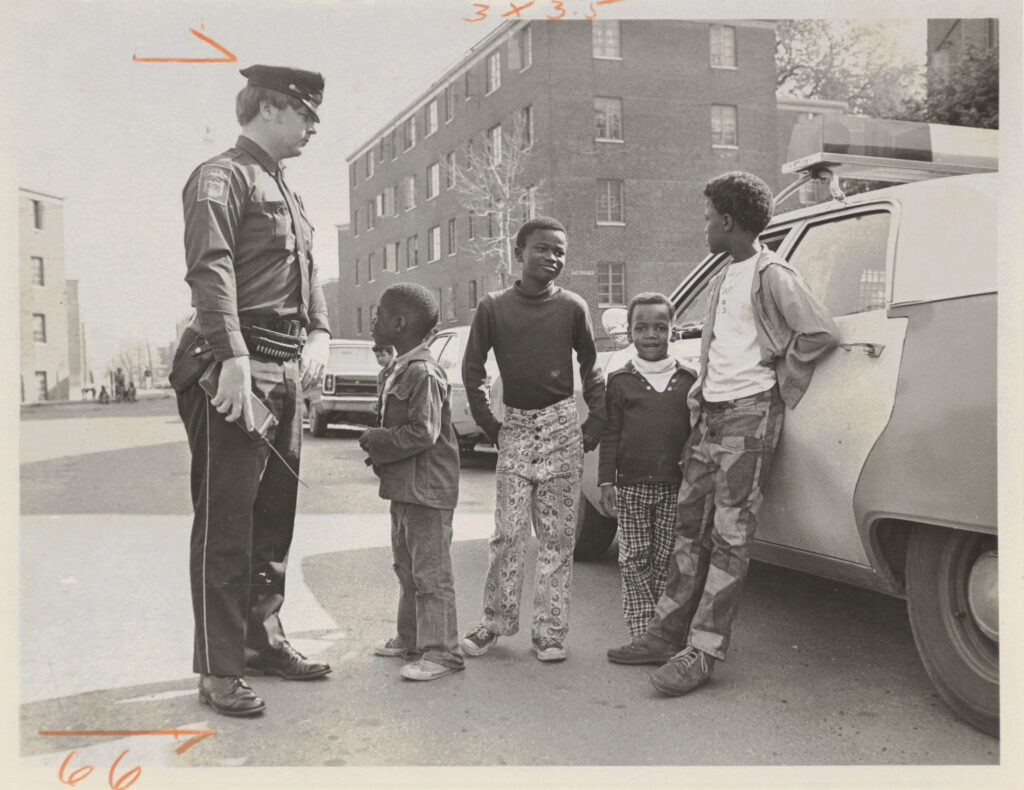

During a pretrial conference in March, the parties “considerably narrow their grounds of difference” and discuss resolving the case by agreement.10 Existing HPD regulations address many of the issues that the plaintiffs had raised in their complaint, and there are potential administrative avenues for improving citizen complaint procedures and officer discipline. The grievances that see no movement during the conference relate to HPD personnel practices, such as the plaintiffs’ demands for diverse hiring. After subsequent deliberations, the case does not go to trial, resolving in a consent judgment in Mid-June. Attorney Schulman feels that the agreement is mutually beneficial for all involved: “I feel that it virtually goes as far as anything can go in writing and now would be up to the good faith of the parties on both sides and, as stated in the stipulation, I feel that the actions of the parties will tell in the future and I think that, in fact, both parties are in good faith and the problem will be resolved.”11

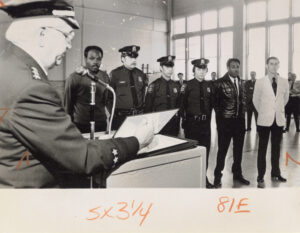

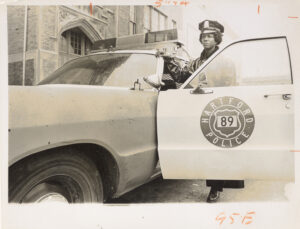

The consent decree allows Judge Blumenfeld to acknowledge the harm caused to the plaintiffs in Cintron v. Vaughn (hereafter Cintron) without finding the HPD liable for constitutional violations. The document is divided into Operations, Recruitment and Promotion, and Training as the distinct categories of procedural improvement. Following extensive negotiations between the parties, the settlement mostly reaffirms existing police guidelines in each category—such as the internal review of complaints, arrest protocol, a bulletin about avoiding racial slurs, and sensitivity training—but does set several new amendments such as banning the use of chemical spray on children who appear to be under twelve years of age, a lowered height requirement for police applicants, and increased frequency of firearms training. Two of the most important policies which the consent decree reaffirms are “Establishment of Use of Firearms Board of Inquiry” (70-19) and the policy for reporting use of firearms by officers on duty (72-42).12 These documents would go through several versions over the coming decades and grow to become central to the life of Cintron; they will eventually come to be known as 1-22 “Firearms Discharge Board of Inquiry” (FDBI), and 1-21 “Firearms Discharges by Sworn Personnel.” The settlement is entered into by both parties and the court “without reference to the affirmance or denial of the allegations contained in the Plaintiffs’ complaint,” but invites accountability in the form of contempt motions filed against the defendants should they fail to follow the stipulations.13 However, it is made clear that such grievances will first be taken up amongst counsel outside of formal court procedure, in the effort to resolve them “in good faith.”14 Only if such attempts at informal resolution fail should plaintiffs enter into contempt proceedings.

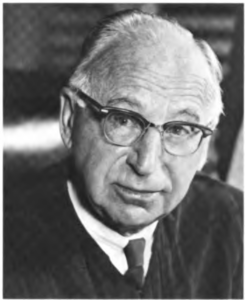

During the settlement hearing, Judge Blumenfeld is generous with praise and commends the counsel for developing this system of resolution based in good faith.

The court is very proud of counsel for the result that has been worked out here because it feels that a great step forward has been made in the creation of an atmosphere of mutual understanding between the parties in an area where misunderstanding is all too easy to arise. And the court is confident that abrasive and highly emotional reactions to possible misunderstandings arising out of this need to maintain a peaceful community has been markedly alleviated. This result achieved by counsel in this decree to which they have both consented is unlike, I think, many compromise settlements where neither party can walk out and feel that they have won everything that they have rightfully felt entitled to. On the contrary, I think that in this settlement both sides can feel fully satisfied that this result has contributed to strengthening the interests which each side has. If I haven’t said that I’m proud of you before, I say so now. And with that, I approve this decree.15

Despite the enthusiasm from counsel and Judge Blumenfeld, reactions to the implementation of the agreement vary. Many activists and community members believe that it does account for every factor of concern, speculating about its anticipated effectiveness. A spokesman for the Concerned Citizens of Bellevue Square, a local organization tracking police conduct in the North End, states that the consent decree is “still not what we were shooting for. There’s still a lot of areas that have not been covered,” such as police entering houses without warrants.16 Chief Vaughan asserts that the decree would only affect “greater awareness on the part of the community as to what we are doing,” and would not change actual police practices.17

Blumenfeld’s case history as a federal judge was generally liberal. He would eventually rule firmly against the actions of the police in the 1983 case of Tracey Thurman v. Torrington. Tracey Thurman of Torrington, Connecticut repeatedly called the police on her abusive husband for assaulting her numerous times throughout 1982 and 1983. Each time the police were called Thurman was met with minimal police response, but would never arrest her abusive husband. During the final incident of extreme violence against Thurman, police officers stood by watching, doing nothing to intervene as her husband brutally attacked her. The officers eventually stepped in to arrest him after he attempted to attack the paramedics on scene. Thurman was hospitalized for eight months and temporarily paralyzed, left with lifelong injuries. Thurman filed a lawsuit against the city of Torrington and the Torrington Police Department for violating her civil rights by not adequately protecting her against her violent husband. Blumenfeld sided with Thurman, arguing that the police should have done more to protect Thurman and other women experiencing domestic violence. This decision was crucial in shattering the perceived invincibility of police judgment, particularly highlighting the consequence of their hesitancy when intervening in situations of domestic violence.

Judge Blumenfeld’s ruling in Cintron is situated in a larger context of consent decrees nationally. Consent decrees as a form of accountability originated after the Clayton Antitrust law in 1914, as a means of resolving a dispute between two parties without an admission of guilt or wrongdoing. Consent decree settlements emerged in cases of corporate disputes as a way to ensure that companies were following the same regulatory laws. These settlement agreements allowed for companies to be held accountable, oftentimes in an area of public concern, to improve certain elements of their business. In the late 1970s and early 1980s, the first cases of socially-focused consent decrees were implemented as a way to increase racial diversity within companies and public service departments. Across the country from Springfield, Massachusetts to San Francisco, California, consent decrees were implemented as a means to reform predominately White police departments to better reflect a diverse community. In Springfield in the early 1970s, after “several lawsuits alleged that Boston police and fire departments discriminated against Black and Hispanic candidates while hiring incoming officers,” an agreement was reached to change the racial breakdown of the police and fire department.18 Cintron figures into this history as one of the first of its kind, as a consent judgment correcting not only racial discrimination in hiring but prejudicial behavior in police activity as well. Cintron sets a precedent for similar cases to follow, emerging as the longest running consent decree against a police department.

Notes

10. Pretrial Order, Section IV, Cintron, et al v. Vaughn, et al, 3:69-cv-13578-KAD (D. Conn. March 15, 1973).

11. Transcript of Settlement Hearing at 4-5, Cintron, et al v. Vaughn, et al, 3:69-cv-13578-KAD (D. Conn. June 18, 1973).

12. Settlement Stipulation, Section II 4 c-e, Cintron, et al v. Vaughn, et al, 3:69-cv-13578-KAD (D. Conn. June 21, 1973).

13. Settlement Stipulation, Section V.

14. Transcript of Settlement Hearing, 7.

15. Transcript of Settlement Hearing, 7-8.

16. Bruce Kauffman, “Minority Settlement Lauded, Decried,” The Hartford Courant, June 20, 1973, ProQuest.

17. Kauffman, “Minority Settlement Lauded, Decried.”

18. Tristan Smith, “Mass. FD Released From 1970s-Era Diverse Hiring Consent Decree,” Fire Rescue 1, July 1, 2022, FireRescue1