Wesleyan University

Carceral Connecticut Exhibition

The timeline chronicles the evolution of systemic issues surrounding race and policing in Hartford, Connecticut, spanning six decades, beginning with the societal upheavals of the 1960s with the historical lawsuit Cintron v. Vaughan to the ongoing impact of judicial reform, urging a reimagining of justice and public safety for the future.

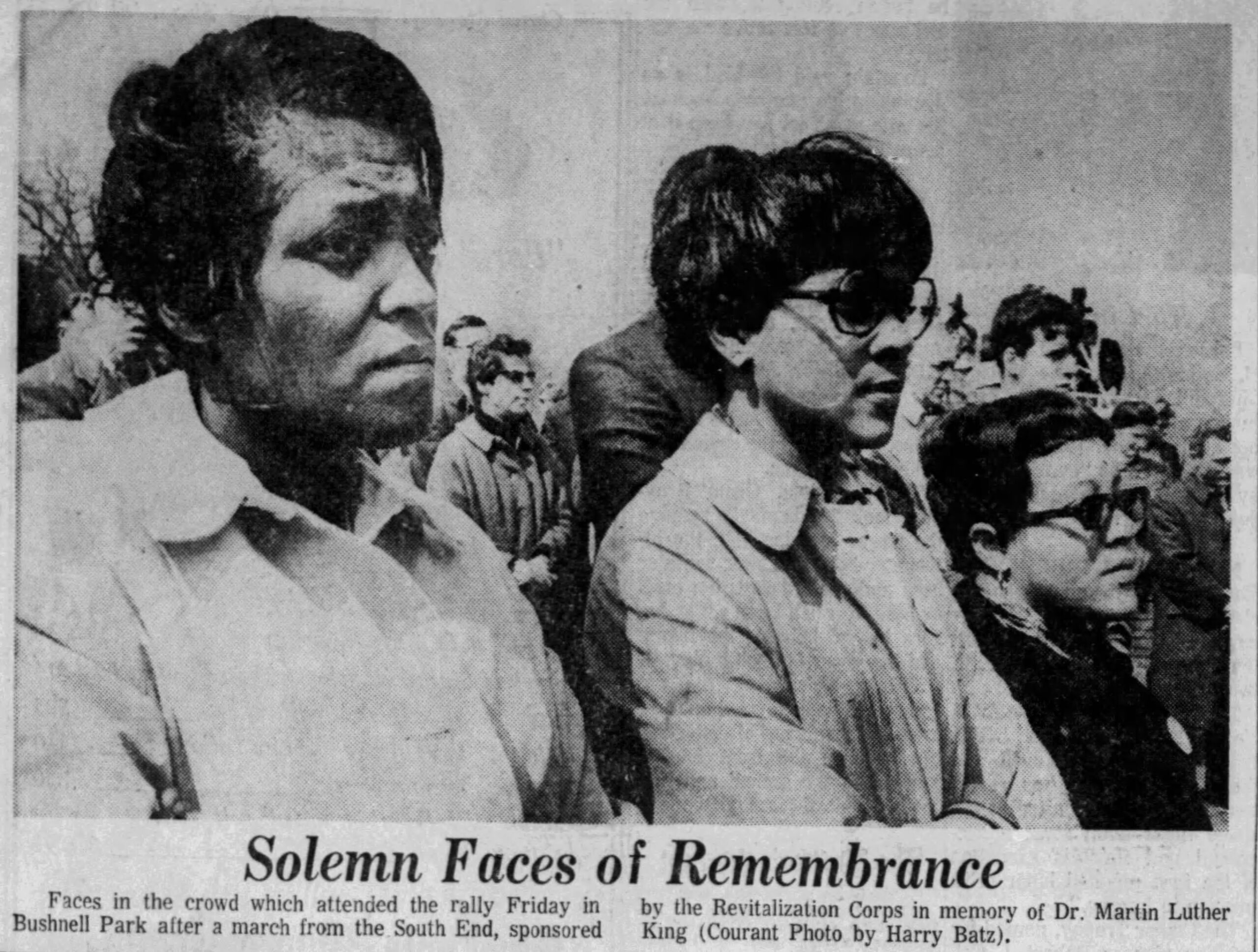

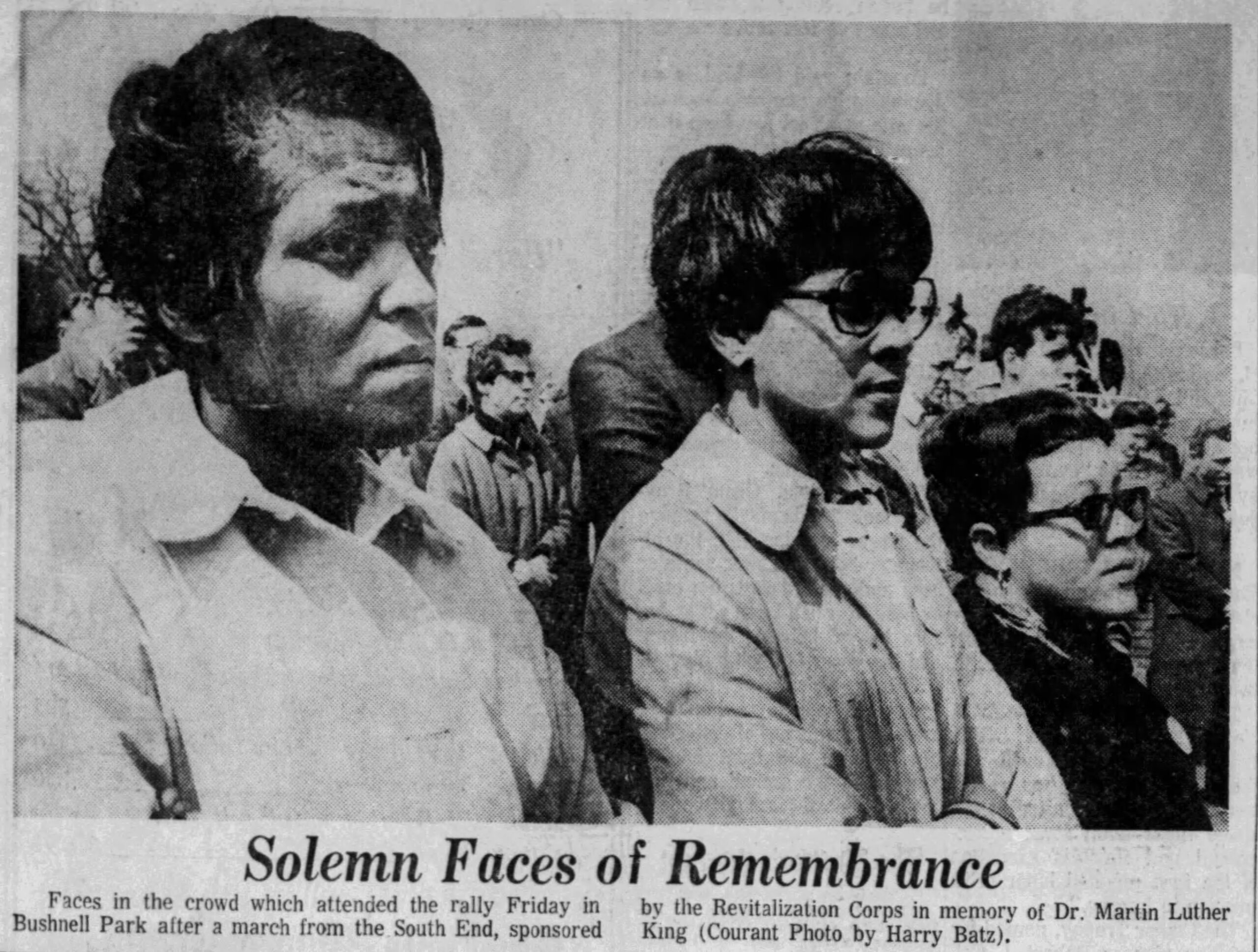

The period of the 1960s has come to be defined by powerful social uprisings against the systemic racial discrimination perpetuated by de facto segregation in educational, legal and social systems. Entirely intertwined with these spheres of violence is the use of excessive force as a weapon of control by law enforcement agencies, as a means to physically uphold these systems of racial discrimination. As December 1969 closes out the decade, members of the Black and Latinx community in Hartford, Connecticut file a class action lawsuit against the Hartford Police Department for subjecting them to unconstitutional and senseless violence. This class action lawsuit would come to be known as Cintron v. Vaughan.

The period of the 1960s has come to be defined by powerful social uprisings against the systemic racial discrimination perpetuated by de facto segregation in educational, legal and social systems. Entirely intertwined with these spheres of violence is the use of excessive force as a weapon of control by law enforcement agencies, as a means to physically uphold these systems of racial discrimination. As December 1969 closes out the decade, members of the Black and Latinx community in Hartford, Connecticut file a class action lawsuit against the Hartford Police Department for subjecting them to unconstitutional and senseless violence. This class action lawsuit would come to be known as Cintron v. Vaughan.

Amid a series of fatal police shootings and public outcry, the Guardians—a fraternal organization of Black Hartford Police officers—perform a walkout to call attention to their grievances regarding a culture of discrimination within the force. This is the context in which local Black and Puerto Rican organizers file a class action lawsuit, Cintron v. Vaughan, against the HPD and city government alleging a pattern of race-based abuse.

US District Judge M. Joseph Blumenfeld denies the city’s motion to dismiss Cintron v. Vaughan. Hartford is sent reeling after several more young Black and Latino men die at the hands of police. A city council committee is convened to investigate police use of force, but they end up recommending no change in guidelines.

In 1973, Judge Blumenfeld resolves Cintron v. Vaughan in a consent judgment between the HPD and minority groups under judicial oversight. Reactions to this decision vary, as many community members believe that the decision does not wholly account for the harmful practices exercised by the HPD. This consent judgment sets a precedent for additional settlements to follow for the next fifty years, constituting the longest held consent decree against a U.S. police department.

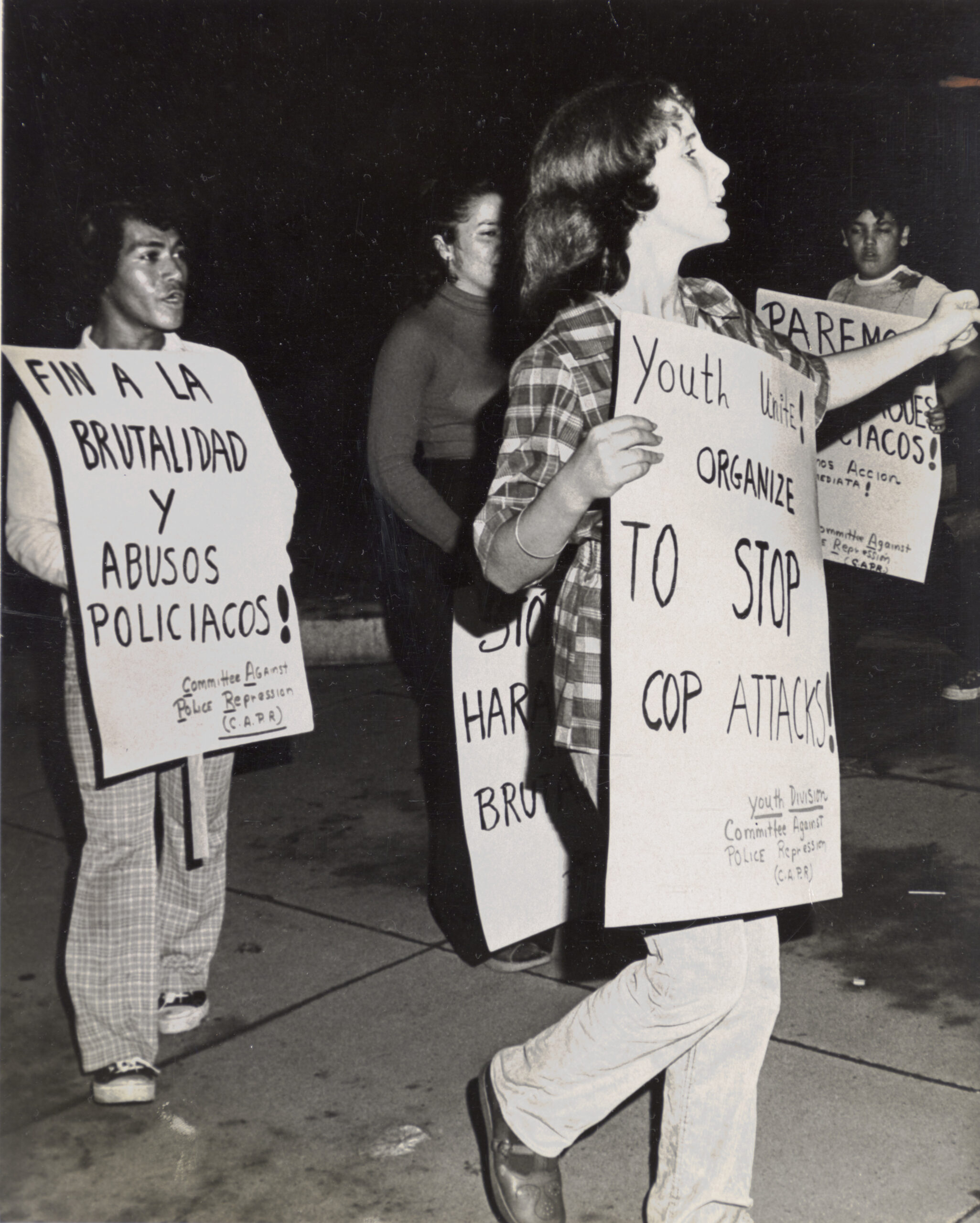

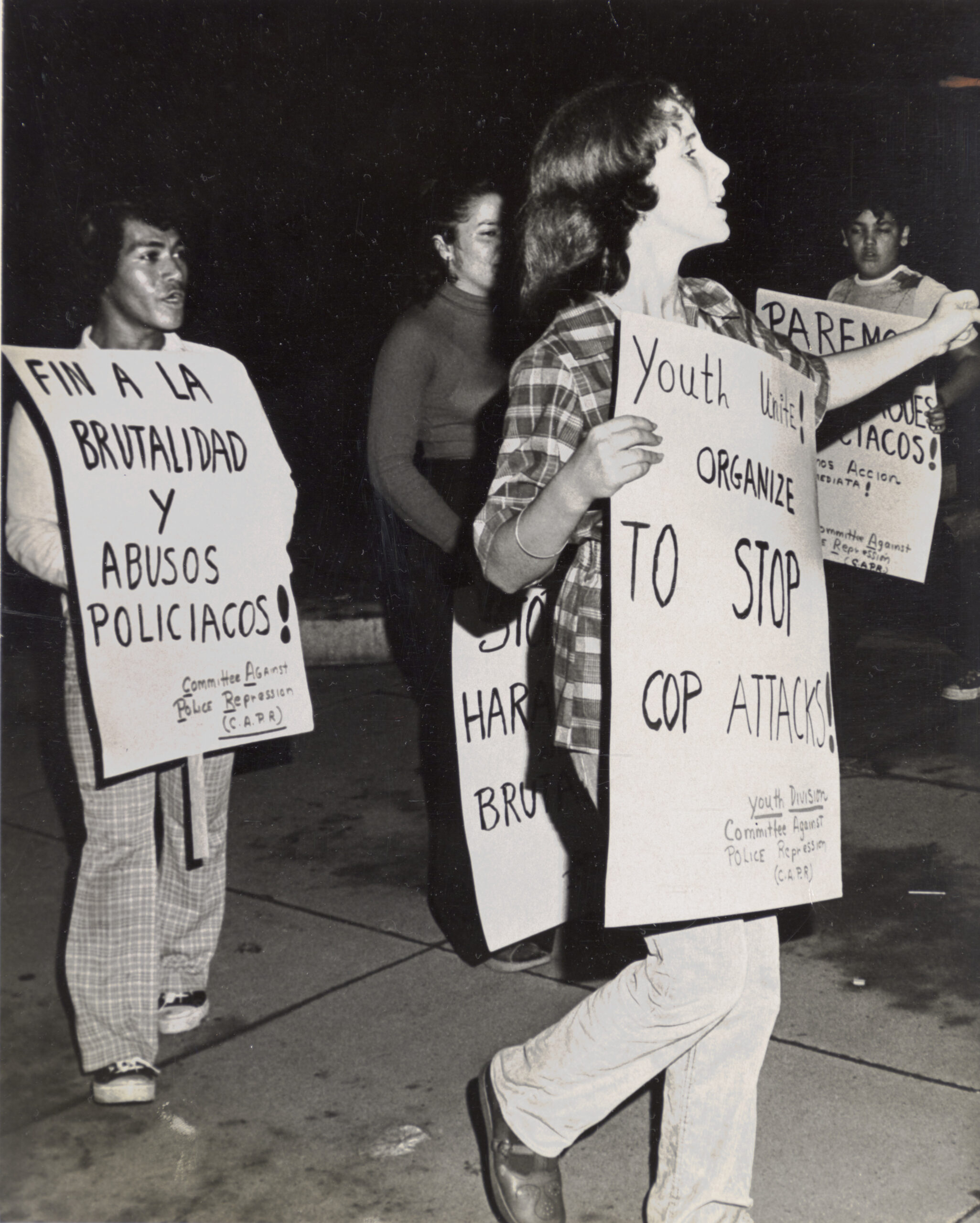

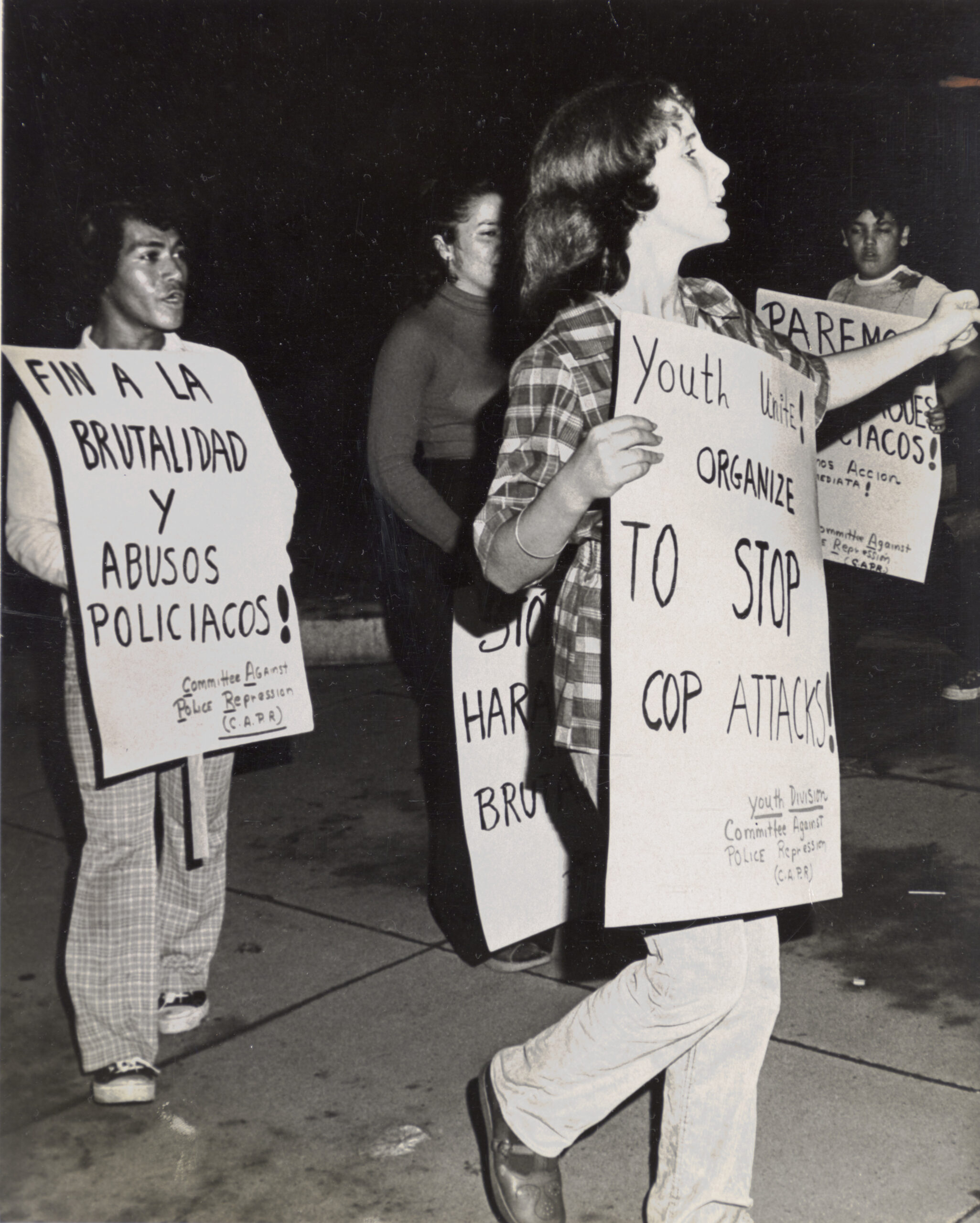

No further action is taken within the consent decree, but Hartford community organizers continue to push for change through direct means. The Committee Against Police Repression (CAPR) organizes a protest in language which mirrors Cintron; they march against “a pattern of harassment and brutality” by the HPD, specifically claiming that officers have been arresting scores of Puerto Rican young people for simply walking down Park Street in the North End. (Source) Representatives of CAPR succeed in getting a meeting with police officials, who promise to investigate complaints of arbitrary arrest and rough treatment in the area. (Source)

There is no activity on the case until 1981, when a group of minority HPD officers file a motion to intervene into Cintron v. Vaughan alleging discriminatory promotion practices. The Guardians had filed a set of complaints with the chief in 1979 concerning these issues, which were never adequately addressed. They ask for an injunction preventing all promotions until the problem is solved. Nothing came of this spate of litigation, and the motion would later be withdrawn in 1985.

Following another gap in case activity, the defendants succeed in changing the terms of the consent decree such that officers can carry their semi-automatic service weapons while off duty.

The HPD comes under scrutiny after Officer Ezequiel Laureano is caught on film striking a handcuffed student during a riot at the University of Hartford. The incident occurs the very same day on which Rodney King is filmed being beaten by the LAPD. Laureano is arrested for assault, and the case causes a public scandal which brings attention to the HPD’s weak structure of accountability. The Hartford Courant publishes a thorough report on the department’s shortfallings and lack of effective deterrents against police brutality, which pressures the department to institute several policy changes.

Tensions rise between the HPD and the city administration. Officers feel that the city is targeting them for political gain, swept up in a national wave of anti-police sentiment ignited by the beating of Rodney King and subsequent LA riots.

The 1994 Crime Bill sets judicial precedent for the implementation of consent decrees against police departments, specifically through Section 14141 regarding the jurisdiction of the Department of Justice in evaluating a police department’s violation of citizenship. Cintron v. Vaughan is of particular interest for this very reason, as it takes place twenty years prior to this perceived authorization, and seems to be left out of the historical memory that centers 1994 as the inception of this practice.

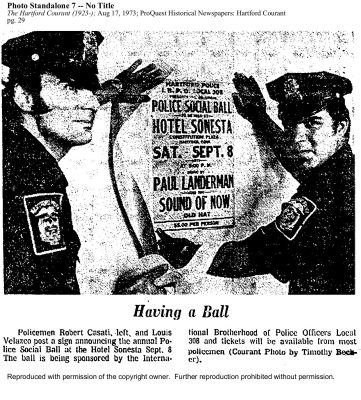

In June 1997, claims of discriminatory conduct are brought against Deputy Chief Robert Casati by a colleague, Sergeant Daryl Roberts.

In January, an internal police hearing is convened to investigate Casati’s alleged misconduct.

HPD Officer Robert Allan fatally shoots fourteen-year-old Aquan Salmon on April 13th. The collective grief following this tragedy unifies local activists, prompting calls to revisit the 26-year-old consent decree as an avenue for accountability.

Salmon’s killing in 1999 brought out deep seated anger around Hartford regarding the HPD’s targeting of minorities and failure to protect those they serve. As the millennium turns, protests across the city give voice to these feelings and community organizers continue to work toward “Justice for Aquan.” Attorney Richard Bieder is enlisted to oversee Cintron’s litigation as Special Master. He finds Officer Allan’s use of force justified, if tragic.

In May, Robert Casati’s discriminatory remarks are defended by Arbitrator Albert G. Murphey in his move to reinstate Casati to his position as Deputy Chief.

The City submits an application to vacate Arbitrator Murphey’s decision excusing Casati’s behavior. In October, Judge Marshall K. Berger grants it. Judge Berger finds Casati’s reinstatement to be a violation of public policy, and in “excess of the arbitrator’s authority under the submission” (Source).

The parties come to an agreement on updated Firearms Discharge Board of Inquiry (FDBI) guidelines, the demands of which were first initiated in 1999 in response to Salmon’s shooting. HPD Officer Robert Murtha shoots an unarmed citizen, Elvin Gonzalez, and the incident’s investigation is obstructed by union members.

The Cintron parties agree on a new civilian complaint procedure, known as the “2004 Order.” Plaintiffs file two motions for contempt, one of which charges noncompliance with the 2004 Order.

The Plaintiffs re-file a motion for contempt alleging that the HPD has not followed the 2004 Order, and another regarding their failure to devise an affirmative action plan to increase racial diversity on the force.

Defendants withdraw consent to the appointment of a Special Master to oversee Cintron, citing the costs incurred by Hartford taxpayers without apparent benefit. (Source)

Following an extensive investigation, Special Master Bieder files a report finding the HPD in violation of five provisions of the 2004 Order. Judge Burns agrees with three of these, and affirms Bieder’s suggested sanctions, including a required public relations campaign to inform citizens about the complaint procedure.

The parties hold several settlement conferences with Magistrate Judge Margolis, which continue into 2009. (Source)

Special Master Bieder submits his second report concerning FDBI issues, specifically the investigations of three shootings that occurred from 2003-2004 including the Murtha shooting. Judge Burns approves Bieder’s contempt findings on several counts. Sanctions consist of a requirement for updated guidelines and training to fix said issues.

Both Cintron parties enter into a new settlement agreement, generally referred to as the “2010 Agreement,” requiring the defendants to revise several procedural protocols. The settlement stipulates that both parties agree to resolve future disputes outside of legal intervention, to the best of their abilities.

Hartford City Council passes a resolution requesting the court not sunset the consent decree until the HPD solves several internal issues.

Plaintiffs file a motion for contempt alleging that there has been no improvement in HPD diversity since the consent decree was enacted, among other violations.

Judge Bryant denies plaintiffs’ motion for contempt as premature. HPD comes under fire for inadequately investigating sexual harassment allegations within the force.

In July of 2020, following the rising Black Lives Matter protests and national outcry against racial violence, Hartford council members again request that the federal court hold on sunsetting Cintron. During this time, the Connecticut state legislature signed into law the Police Accountability Act. This relatively impressive piece of reformative legislation includes both performative measures and forceful ones, such as curbing qualified immunity.

Plaintiffs file a motion for contempt and respond to an order to show cause in an attempt to prevent Cintron from dissolving. Defendants oppose both documents, arguing that the HPD has made substantial progress and reforms in recent years.

Judge Karen Dooley dissolves Cintron, ruling all pending violations inconsequential. She affirms the intention of the consent decree, and recommends that future efforts of police reform move within the powers of “the police department itself, the City of Hartford, and the greater Hartford community.”