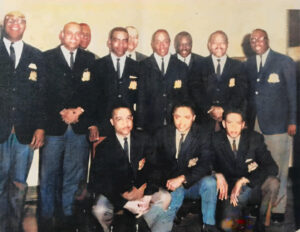

Original members of the Guardians, 1962. Front row: Alfred Cicero, Edgar Robinson, & James “Jim” Murphy.

Middle row: Thomas Fuller, Clyde Rogers, Walter Clark, Marvin “Mutty” Jones, Norman Wallace, & Joe Shaw.

Back Row: Art Williams, Tom Fuller, & Alfred Gaddy, Sr. Credit: Hartford Guardians

The Guardians are an organization of Black Hartford police officers founded in 1962 and still active today.1 In the late 1960s, they began organizing to demand that the department address racism within its ranks and administration. The first major action occurred in the summer of 1969, during which the Guardians released a list of grievances regarding discrimination within the HPD and orchestrated a sick-call protest. They received support from the Council of Police Societies, a national organization of Black police officers. The next year, the Guardians released a statement vowing to physically intervene should they witness bigotry or racial violence by a white officer. The Guardians continued to organize around internal discrimination through the 1980s, but no longer hold that role.

Sick Day Walkout: In late July 1969, Guardians president Thomas Fuller threatened a walkout if the HPD administration did not address claims of internal discrimination; “we want the whole department desegregated.”2 Fuller and Chief Vaughan were set to meet and discuss grievances on August 3rd. Vaughan canceled the meeting after finding out that forty to fifty people would be attending, including people outside the department such as ministers and NAACP representatives. In response to the cancellation, the Guardians carried out the walkout on August 1st in which forty two of the force’s fifty seven Black officers called in sick. The protest lasted a few days, with fifteen to twenty two officers calling in sick each day until Vaughan agreed to a new meeting. During the walkout, white officers harassed Guardians members by showing up at their homes unannounced and driving around with cameras in unmarked vehicles, hoping to prove they were not sick. City Manager Elisha Freedman threatened to fire the absent officers en masse if their health were proven.

On August 4th, several leaders of the local NAACP visited Fuller’s home; Glenda Copes, Wilber Smith, and William Jones. Police Union lawyer Joseph Fazzano was there as well, purportedly calling on his ill friend. Later that day, the Guardians sent copies of their grievances to the press, Chief Vaughan, City Council members, City Manager Freedman, and the police union. Himageoutline ere is the original list, courtesy of Attorney Sydney Schulman:

Grievance Procedure and Discourse: The Guardians had support from the National Council on Police Societies, an organization representing over 7,000 Black officers. The council’s president, Alphonso Deal, came to New Haven to help negotiate with city officials. The police union adopted the Guardians’ grievances, and they were submitted for review as procedure stipulated. The union would present the grievances to successive members in the police hierarchy, and if they were unable to remedy them, they would go to the State Board of Mediation and Arbitration. However, Fuller lacked confidence that this system would yield results; “I feel this is a racial problem, and that the union might not be able to handle it.”3 If it went to a vote of the union body, he expected a dead end.

The Guardians maintained that discrimination primarily came from the top of the department, not from the white rank-and-file. They released a statement to the press August 17th clearing up misinformation:

Someone or some group has found it necessary to make the grievances presented by the black officers appear to be an issue of white patrolmen against black patrolmen; sergeants against black patrolmen; captains and lieutenants against black patrolmen; but we maintain that this is not so… the need for unity among all officers, black and white, is such that it would be chaotic if the situation reached a point where we denied each other the basic brotherhood of police officers … The repercussions of this chaos would be felt by every citizen of this city.4

Along with the statement, Guardians board members shared three anecdotes which purportedly proved discrimination from superiors rather than fellow patrolmen. However, two of the stories also involved racist actions on the part of patrolmen. For example, Fuller spoke of an incident in which two white officers called in sick on days when they were supposed to ride in cruisers with Black officers. They were not required to show doctor’s notes and their pay was not docked, in contrast to half of the Black officers who had called in sick during the walkout and lost pay. The story does reveal bias on the part of the police administration, but it does a poor job of absolving the white rank-and-file.

Three weeks after the walkout, Chief Vaughan responded to the Guardians’ grievances point by point, denying all. He claimed that the HPD had the best record of recruitment and retention of Black officers in New England, and that the allegedly discriminatory assignments were in fact fair and reasonable. He argued that there were in fact Black officers in specific departments that the Guardians pointed out for their lack; for example, the booking department employed a Black truck driver. “He kills his statement right there,” a Guardians spokesman said.5 Fuller rejected Vaughan’s entire response, telling the Hartford Courant that it consisted of no more than “half-truths, misstatements, and inaccuracies.”6 Eventually, the list of grievances made it to the State Board of Mediation and Arbitration, where they were found lacking in evidence in January 1971.

The discourse around the Guardians’ grievances revealed the complex role of Black police officers in the North End. All of the department’s Black patrolmen were assigned to the neighborhood, a predominantly Black and Latino area. The North End is where most of Hartford’s crime occurred, so an officer would receive numerous (sometimes nonstop) calls each night, often related to traumatic events. In contrast, the officers assigned to the predominantly white South End had comparatively calm duties. The Guardians compared the North End to a war zone; they argued that if soldiers are entitled to r & r, the North End patrolmen should be too, because their jobs are just as trying. This problem is at the heart of several of the Guardians’ grievances, such as desegregation, ending discrimination in assignment, and increasing indoor relief assignments for Black officers, exhausted from their time patrolling the North End.

In Chief Vaughan’s response to the North End issue, he spoke of the value of assigning minority cops to minority areas, and pointed out that local civil rights leaders had requested this. When the grievances were passed onto City Personnel Director Robert Krause, he too weighed differing interests in his response to the North End question. Krause asked what credence should be given to the report of the President’s crime commission, which recommended assigning minority officers to minority areas, or to the neighborhood groups that had requested such protocol. “What respective priority do we assign to the desires of the policemen and the desires of the citizens? Does the police department exist primarily for the protection of the citizens or for the convenience of the policemen?” wrote Krause.7 The assignment of minority cops to minority areas is still raised today as a technique of police reform intended to limit police violence and community tensions, although its efficacy has been largely disproven; see the work of Devon Carbado and James Forman Jr., taken up in this project’s section on Cintron v. Vaughan.8

Lyric Dance Hall Disturbance: The Guardians brought attention to racism within the Hartford police force again in November of 1970, following an altercation between two officers on the 14th. Police responded to a report of fighting outside a Puerto Rican community dance held at the Lyric Dance Hall. As officers arrived, the chaos among the crowd deepened and people began shouting and resisting police intrusion. Eleven people were arrested. While arresting a young Puerto Rican woman, white police officer David Calvert attempted to drag her into the police van. Off-duty patrolman Gerald Pleasent, Black and “Spanish-speaking,” told Calvert to stop and then grabbed his arm to make him let go of the young woman. According to police investigators, Calvert pulled away and Pleasent punched him in the face. According to Pleasent, Calvert threw the first blow. Calvert ended up with fractured bones in his nose, and Pleasent was suspended indefinitely without pay.

The disturbance incited a wave of support for Pleasent, who was already a popular officer. Some residents of the North End who held hostile feelings toward police still trusted Pleasent, who treated them with respect, kindness, and dedication; “like human beings,” according to Barbara Henderson, chairman of the Association of Concerned Citizens (see below). 9A week after the fight, people marched outside City Hall in protest of Pleasent’s suspension and one hundred filled the city council chambers to present demands on police-community relations. Attorney Sydney Schulman of Cintron v. Vaughan presented the following demands: That the HPD recruit more minorities through simple changes like lowering the height requirement (the department was 1% Puerto Rican in a city of 12%); institute psychological testing for all officers and dismiss those with racial prejudice, inclinations toward violence, or inability to deal with stressful situations; and require sensitivity training so that officers can better understand Puerto Rican culture.

Members of the Puerto Rican community were outraged at how the city handled the Lyric Hall disturbance, beyond Pleasent’s suspension. Ramon Quiros, president of the club that sponsored community dances at Lyric, had been asked by a sergeant to help disperse the crowd that night. When he started doing so, a patrolman interpreted his gesturing and shouting in Spanish as an incitement of violence, and hit him in the head with his nightstick. Quiros was then arrested for breach of peace. Victor Solis, a firefighter, went to police headquarters the same night to complain about unfair arrests, and was himself arrested. Pleasent, Quiros, and Solis had all been helping the city with efforts aimed at community relations, and were upset by their unfair treatment. They met with sympathetic city councilmembers Collin B. Bennett and Allyn Martin two days later, who called for the objective investigation of Pleasent’s suspension. Martin had no faith in the HPD’s internal review; “when this is all over, what have you got? You’ve got a police version and a citizens’ version.”10 As always, the police version would be accepted.

Pleasent received twenty days suspension without pay, and Calvert faced no consequences. Calvert was fired three years later, in July of 1973, after he shot someone over a minor traffic violation. The traffic incident followed a long history of violence, including the Lyric fight, a bar brawl, the use of mace over a parking ticket, intoxication, and insubordination. Calvert had also been sued by a citizen who claimed he had used excessive force during an altercation over a parking ticket.

Statement on Bigotry: The Guardians were vocal supporters of Pleasent, and they took the opportunity to make a major stand against institutionalized racial violence. One week after the fight at Lyric Dance Hall, the Guardians released a statement announcing that they would no longer permit bigotry by white officers and would physically intervene:

The time is at hand when Black and other minority police officers and citizens cannot, and should not, stand by and permit White, bigoted police officers to unjustly assault and abuse the dignity of the Black, the Puerto Rican, or for that matter, any human being… if it becomes necessary for Black officers to physically interfere in further unjust acts of police brutality, then the public can very well look forward to a new breed of Black officers… In good faith we cannot and shall not permit Black and Puerto Rican womanhood and manhood to be exposed to such bigoted assault. The days of the yassah-nosah officers are almost over.11

President Robert L. Kendrick and Fuller, now chairman of the Guardians’ board of directors, said the statement was approved by three quarters of the force’s fifty one Black officers. This included all of the Guardians and a few non-Guardians. The Hartford Courant reported on the results of a poll conducted among ten of the department’s officers, of which six agreed with the Guardians’ statement, two disagreed, and two declined to answer. One of the dissenters, former Guardian Sergeant Saul Chafin, told the Courant; “I’m opposed to an interference of any officer by another policeman. If there are complaints, they should be taken to the chief.”12 The other, Sergeant Nathaniel Davis, said “this is an unprofessional attitude coming at a time when we are trying to professionalize the department.”13 Davis invoked the police manual’s guideline regarding cooperation among officers and exercising patience in times of danger.

One of the officers who agreed with the Guardians’ statement said it was “part of the new Black awareness.”14 Another supporter explained that “there are a lot of new, younger guys joining the force now—and they’re swept up in the tide. This is happening more and more, especially in the bigger cities. They’ve had pushing and shoving matches between policemen in New York. In Detroit they’ve even fired on each other.”15 All supporting respondents said they would physically restrain a white officer committing brutality, but not everyone would actively hit them. Some white officers agreed with the statement as well, regarding it as common sense; “If I saw a policeman beating on somebody I’d try to restrain him too. I’d arrest him.” Nonetheless, Chief Vaughan deplored the statement as a promise of brutality itself. “We waited a long time before we took this stand,” Fuller told the Hartford Star. “The problem is that the black policemen have to make a choice between the community and the police.”

Bobby Seale, co-founder of the Black Panther Party, wrote in support of the Guardians’ statement from his cell in Montville Jail. He referred to the Hartford organization as “beautiful humane brothers who have taken a people’s community stand against Fascist, racist police brutality.”16 Speaking for the Black Panthers, Seale wrote that the Party “supports and salutes the Guardians for the simple reason that a better society can begin to be constructed upon the now-falling ruins of white racism in Amerika.” This statement was a full circle moment for Thomas Fuller, who had been inspired by the Panthers in his leadership of the Guardians. In a controversial address to the Springfield NAACP in February of 1970, Fuller said he would have joined the Panthers had he not been a police officer. The Hartford Star reported that it was the first time a member of the Panthers voiced support for any segment of a police department.

Concerned Citizens: A community group called the Concerned Citizens was organized in January of 1971 after the Guardians’ statement on police brutality, pledging their support for their cause and other forms of police accountability such as a civilian review board. In February, the Concerned Citizens opened a Civilian Complaint Center run by volunteers. The main purpose of the center was to coordinate collection of complaints against police, which were rarely followed up with by the HPD’s internal affairs division. The group’s president, Leroy Clemons, told the Hartford Star “everyone recognizes the need for police protection, but policemen who overreact or provoke incidents are not serving the community or themselves. If police are not disciplined for misconduct, they lose the respect and support of the citizens they serve. Without that support, fair and effective law enforcement become more difficult.”17 In its first month of operation, the center received fourteen complaints, ten of which were sent on to the Internal Affairs Unit. The majority of the complaints are related to excessive force and false arrest, including the beating of a Vietnam veteran and use of mace on young people. The Concerned Citizens would send follow ups inquiring into the status of the complaints, and notified Chief Vaughan if they were not responded to.

The Concerned Citizens organized and advocated for a range of initiatives aimed at police accountability beyond the complaint center. In 1971, they also spearheaded a push for police name tags, a self-evident and simple accountability tactic. They faced resistance from the department over the idea; concerns included the risk of the name tag pins injuring officers, and the names washing away in the rain. The next year, the group worked closely with Chief Vaughan on community-relations programs such as coordinating Spanish-speaking volunteers to aid police officers with translation. The Concerned Citizens were also critics of media power, in particular the spectacularization and bias evident in coverage of crime among Hartford’s North End. They argued that recent statements from top city officials and subsequent media reporting surrounding two 1971 incidents of juvenile crime effectively foreclosed the possibility of fair trial for the minors.

Guardians Newspaper Coverage

- May 27, 1964: HC “Thursday Funeral Set For Policeman Jennings”

- June 12, 1968: HC “Negro Group Backs Discrimination Complaint”

- November 16, 1968: HC “Official Testifies for Hankins In Bloomfield Police Bias Case”

- December 6, 1968: HC “Negro Club Backs its President”

- January 22, 1969: HC “Policeman Hankins Dies; In Bias Case”

- April 16, 1969: HC “Coll Urges City Police Centers”

- July 22, 1969: HC “’Guardians’ Admit Ranks Split”

- July 26, 1969: HC “Black Policemen Mull Strike, Charge Bias in Assignments”

- July 26, 1969: HC “Black Policemen Mull Strike, Charge Bias in Assignments”

- August 4, 1969: HC “Black Police ‘Illness’ Grows”

- August 5, 1969: HC “Vaughan To Meet With ‘Guardians’”

- August 5, 1969: HC “Negotiator Knows Tough Jobs”

- August 6, 1969: HC “Chief, Black Police To Discuss Demands – Within Union Rules”

- August 7, 1969: HC “Black Police Group Presents Grievances to Union for Action”

- August 7, 1969: HC “Black Policemen List Grievances”

- August 9, 1969: HC “Black Police, Chief Name Talk Date”

- August 17, 1969: HC “Black Police Say Bias Comes From Top”

- August 20, 1969: HC “Chief Vaughan Finds No Bias Against Blacks”

- August 21, 1969: HC “Fuller Denies He Negotiated for Black Police”

- August 22, 1969: HC “Personnel Chief Gets Black Police Wants”

- September 9, 1969: HC “No Ruling Made on Guardians’ Grievances”

- September 10, 1969: HC “Black Policemen To Take Grievances to State Board”

- September 11, 1969: HC “Policemen Vote Conditionally To Accept Offer of Meeting”

- September 13, 1969: HC “Guardians, Union, Vaughan to Meet”

- September 14, 1969: HC “Symposium Will Probe ‘Deadly’ Police Force”

- September 14, 1969: HC “Symposium To Discuss Force Use”

- September 26, 1969: HC “Police Officials, Union, Guardians Hold Long Session On Grievances”

- October 4, 1969: HC “Police Dispute Linked To Total Confrontation”

- November 24, 1969: HC “Black Police Parley Charges City Bias, Demands Remedies”

- December 11, 1969: HC “Mayor Says Suit Good Thing for City”

- December 30, 1969: HC “Bias Complaint To Union Is Planned By Guardians”

- December 31, 1969: HC “Union Leader Denies Charge”

- January 1, 1970: HC “Guardians Intend to Sue Police Union for Dues”

- January 1, 1970: HC “Riots, Sudden Deaths Troubled Police”

- January 16, 1970: HC “Policemen Union Elects Detective To Presidency”

- June 22, 1970: HC “Black Police Attack Own Department”

- February 10, 1970: HC “Policeman Facing Disloyalty Charge”

- February 27, 1970: HC “Police Discontinue Fuller Investigation”

- March 4, 1970: HC “Cicero Elected President of Guardians”

- April 7, 1970: HC “Black Policemen Favor City Probe: Vote Defies Resolution Of Union”

- June 11, 1970: HC “Fuller Named to Board Of Black Police Council”

- June 22, 1970: HC “Black Police Attack Own Department”

- October 3, 1970: HC “Bennett Urges Police To Recruit From Minorities”

- October 15, 1970: HC “Black Policemen Charge Bias in Force Recruiting”

- October 31, 1970: HC “Black Policemen Call For Chief’s Dismissal”

- November 4, 1970: HC “PBA Head Hits Charges Of Police Promotions Bias”

- November 20, 1970: HC “Black Police to Curb Conduct of Colleagues: ‘Brutality’ By Whites Is Target”

- November 21, 1970: HC “Chief Says Guardians Create Police Discord”

- November 21, 1970: HC “More Minority Police Sought by Councilmen”

- November 22, 1970: HC “Police-Community Relations Protested by Minority Units”

- November 22, 1970: HC “Bobby Seale Supports Guardians’ Statement”

- November 25, 1970: HC “Pleasent Fails Police Lie Test”

- December 3, 1970: HC “NAACP Backs Guardians On ‘Brutality’”

- December 4, 1970: HC “Guardian Pledge”

- December 5, 1970: HC “Black Recruiter Gets 12 Bids”

- December 15, 1970: HC “Policeman Suspended For Fracas: Finding Backs Chief’s Action”

- January 1, 1971: HC “Deadly Force Year’s Biggest Issue”

- January 7, 1971: HC “Guardians Seek Black Inspector”

- January 12, 1971: HC “City Policeman Balks at Order To Trim Hairdo”

- January 12, 1971: HC “Black Police Threaten To Leave Union, PBA”

- January 13, 1971: HC “Police Union President Discounts Threat Of Mass Resignations by Black Members”

- January 14. 1971: HC “Board Turns Down Guardians Charges”

- January 14. 1971: HC “’Concerned Citizens’ Form In Support of Guardians”

- January 15, 1971: HC “2 Police Groups Join In Skirmish With Guardians”

- February 26, 1971: HC “Police AFL-CIO Swap Threat Charges”

- March 19, 1971: HC “Citizens Protest Crime Statements”

- March 20, 1971: HC “Whole Judicial System Said Almost in Shambles”

- April 6, 1971: HC “Police Assessed”

- May 17, 1971: HC “State Group Formed By Black Policemen”

- May 25, 1971: HC “Guardians Ready To Sue On Beards, Hair Issue”

- May 27, 1971: HC “Policeman Who Defied Haircut Order Is Fired”

- June 2, 1971: HC “Groups Protest Policeman’s Firing”

- June 11, 1971: HC “Lawman Reinstated In Haircut Dispute”

- October 20, 1971: HC “Improved Race Relations Cited”

- November 18, 1971: HC “City Police Revising Hair Length Regulation”

Concerned Citizens Newspaper Coverage

- January 14. 1971: HC “’Concerned Citizens’ Form In Support of Guardians”

- February 13, 1971: HS “Civilian Complaint Center Opens”

- March 19, 1971: HC “Citizens Protest Crime Statements”

- April 3, 1971: HS “Citizens Urged to Air Complaints”

- May 22, 1971: HS “Mayor Hears Pleas to Keep Pleasent at C.O.T.”

- June 2, 1971: HC “Groups Protest Policeman’s Firing”

- June 5, 1971: HS “Citizens Support Pierce”

- August 31, 1971: HS “Nametags for Cops”

- January 22, 1972: HS “To Get Police Identification”

- March 25, 1972: HS “Community Wants Fuller to Direct Police Center”

Notes

1. There are multiple other Guardians organizations in different cities such as NYC, New Haven, and Bridgeport. Although all are fraternal organizations of Black police officers, the affiliation between them is unclear. The group is sometimes referred to in the Courant archive as a branch of the Connecticut Guardians, but I have not yet found records of such a group. National organizations include the National Organization of Black Law Enforcement Executives (NOBLE) and The National Association of Black Law Enforcement Officers, Inc.

2. “Black Policemen Mull Strike, Charge Bias in Assignments,” Hartford Courant, July 26, 1969, ProQuest.

3. John Sherman, “Black Police Group Presents Grievances to Union for Action,” Hartford Courant, August 7, 1969, ProQuest.

4. Jean Tucker, “Black Police Say Bias Comes From Top,” Hartford Courant, August 17, 1969, ProQuest.

5.“Personnel Chief Gets Black Police Wants,” Hartford Courant, August 22, 1969, ProQuest.

7. “No Ruling Made on Guardians’ Grievances,” Hartford Courant, September 9, 1969, ProQuest.

8. See Devon Carbado and L. Song Richardson, “The Black Police: Policing Our Own,” Harvard Law Review 131, no. 7 (2018). See also James Forman Jr., Locking Up Our Own: Crime and Punishment in Black America (New York City: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2017).

9. “Mayor Hears Pleas to Keep Pleasent at C.O.T.,” Hartford Star, May 22, 1971.

10. William Kiefer, “Councilmen Ask Query Into Police Suspension,” Hartford Courant, November 17, 1970, ProQuest.

11. Edward Wendover, “Black Police to Curb Conduct of Colleagues: ‘Brutality’ By Whites Is Target” Hartford Courant, November 20, 1970, ProQuest.

16.“Bobby Seale Supports Guardians’ Statement,” Hartford Courant, November 22, 1970, ProQuest.

17. “Civilian Complaint Center Opens,” Hartford Star, February 13, 1971.