Incident: In March 1970, the HPD set up a plainclothes unit to monitor nine recent purse snatchings in the North End. On March 14th, nineteen-year-old Gary “Mike” Hansley stole someone’s purse outside Mott’s supermarket, knocking her down in the process. Officer Elden Thibodeau and his partner received word of the theft and immediately saw Hansley running with something under his arm. Officer Thibodeau chased Hansley, yelled “Stop, I’m a police officer,” and then threatened to shoot four times. Hansley did not stop running, so Thibodeau fired a shot down low as Hansley vaulted over a fence. Hansley happened to stumble as he landed, such that the bullet entered his lower back and then heart. He was pronounced dead on arrival at the hospital. The Hartford Courant reported on the scene: “A youth, who police said was a relative of Hansley’s caused a disruption at St. Francis Hospital shortly after Hansley’s body was brought in. Richard E. Harris, 18 … was arrested with breach of peace.”1 This detail, mentioned in passing, opens beyond the article’s cold language and transcends it. It reveals a bright trace of the community which held Hansley in life and would honor him, tirelessly and angrily, in death.

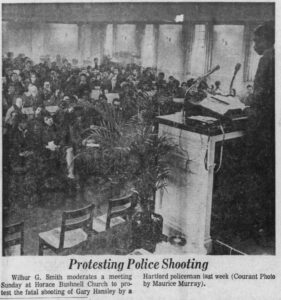

Community Response: The killing led to outrage across Hartford. Mayor Ann Uccello held a meeting with Black community leaders who called for Officer Thibodeau’s suspension, stricter regulations regarding police use of firearms, and closer cooperation between the police and citizen groups. The Spanish Action Coalition issued a statement: “We trust that guidelines will be revised to bring them into line with present standards of human value extent in our community.”2 Hartford’s Human Relations Commission, led by Reverend Alfred White, also asked for Thibodeau’s suspension, along with an end to warning shots, immunity for any witness of a police shooting, cooperation with the Oakland Civic Patrol (see below), and an emergency meeting of the state legislature to address “the worsening race relations of Connecticut.”3 The commission also called a mass rally at Horace Bushnell church, a hub of local political organizing at Albany Avenue and Vine Street in the North End.

Subsequent meetings at Horace Bushnell yielded petitions and protests outside the HPD headquarters. Groups involved included the Hartford chapter of the Connecticut Civil Liberties Union, the Welfare Mothers, the Vine Street Tenants Association, Greater Hartford Council of Churches, and Welfare Recipients Are People. The Community Renewal team, Hartford’s eight million dollar anti-poverty program, released a statement expressing dissatisfaction with the information offered by the police on Hansley’s shooting.

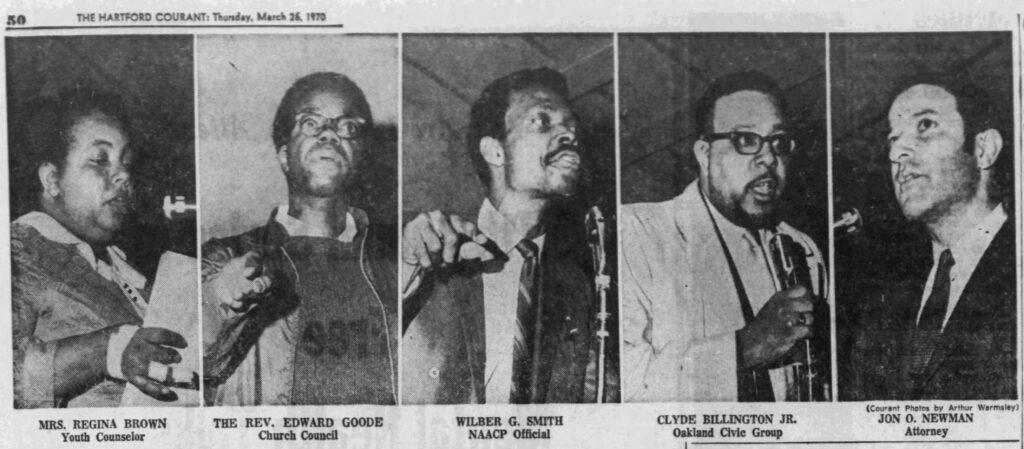

The Horace Bushnell activity culminated in a city council meeting on March 24th. Over 300 people showed up to lend support to a set of community resolutions being presented along with a petition signed by 1,500. The council suspended their rules to allow four citizen representatives to speak, rather than one. Regina Brown, a youth counselor at Horace Bushnell, read three resolutions: that there be a policy under which any officer who has killed someone be suspended without pay until the investigation is over; that police only use guns when someone’s life is in imminent danger, including their own; and that the city council explore the use of tranquilizer guns so that an officer shoots to apprehend a suspect, not to kill.

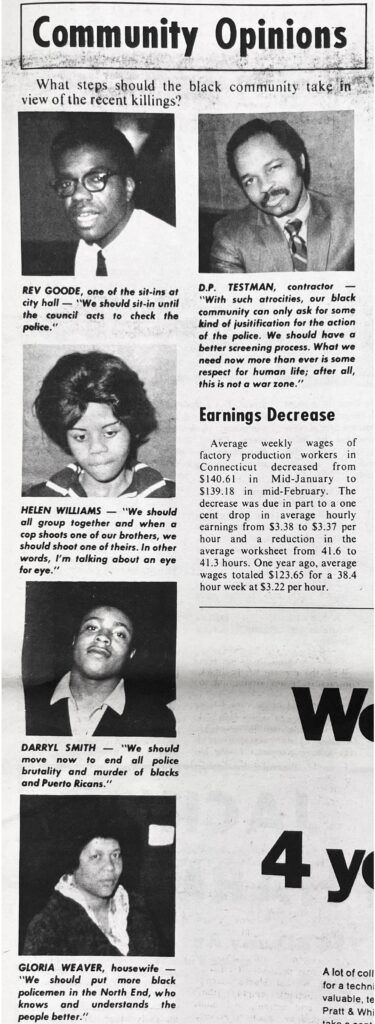

By April, the city had seen two more shootings of young men at the hands of police (William Casey and Abraham Rodriguez, below), which increased civilian pressure on Hartford officials. Protests were held outside of HPD headquarters and at the home of Mayor Ann Ucello. Reverend Edward Goode, an original plaintiff on Cintron v. Vaughan, was one of many who orchestrated sit-ins at city hall with the aim of provoking the city council to institute checks on police power. That month, the Hartford Star, Hartford’s most prominent Black newspaper, asked a range of citizens “What steps should the black community take in view of the recent killings?” Two responses represent the wide range of thought present in local discourse at the time.

- D.P. Testman, Contractor – “with such atrocities, our black community can only ask for some kind of justification for the action of the police. We should have a better screening process. What we need now more than ever is some respect for human life; after all, this is not a war zone.”

- Helen Williams – “we should all group together and when a cop shoots one of our brothers, we should shoot one of theirs. In other words, I’m talking about an eye for an eye.”4

Community engagement, initially spurred by Hansley’s death and increasingly inflamed by subsequent shootings, would lead to the city council committee investigating police use of firearms (See City Council Committee on Police use of Firearms).

Investigation: Officer Thibodeau was found to be acting within police guidelines on deadly force, which followed Martyn v. Donlin. In Hansley’s case, Thibodeau was allowed to shoot because Hansley had knocked down his victim, constituting the felony of robbery with violence. Thibodeau was officially absolved of any wrongdoing by Coroner Irving Aronson on May 7th. The officer was reassigned to an administrative position, common practice when a police officer is involved in a shooting that causes them emotional trauma. In March of 1971, attorney Samuel Bernstein sued Officer Thibodeau for $300,000 on behalf of Hansley’s estate. Hansley’s mother commented, “even if Mike was guilty of the crime, then he should have been tried and punished accordingly; but is a pocketbook worth a person’s life?”5 There is no documentation of the suit’s result, but considering similar cases at the time, it is safe to assume that no damages were awarded.

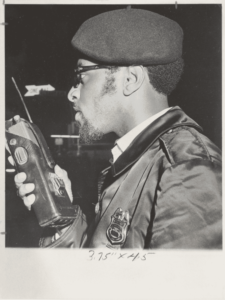

Oakland Civic Patrol: Hansley’s death had resulted in calls for more cooperation between the police and local civic patrols, specifically the Oakland Civic Patrol (OCP), organized in October 1969. Patrol leader Timothy Martin said that such communication could have saved Hansley’s life; Martin knew Hansley and his home address, and could have found him easily should the police have lost him that day. Unfortunately, the patrol was not yet active at 7 pm, but regardless it is doubtful that the police would have reached out. The OCP extended their hours after this incident.

While still enmeshed in the policing system, the unarmed OCP provides a compelling case study in alternative forms of public safety. Volunteers received training from the HPD in first aid, walkie-talkie operations, emergency procedures, health and building code violations, mob psychology, and various crime situations. When the police union objected, they had to give up the walkie-talkies. In Martin’s words, the OCP was “not a substitute for the police but merely treating people as humans.”6 Their crime-detecting strategy was simple: they would walk around at night in a twenty-five-block area around the North End’s Albany Avenue and speak with young people. Everyone knew that the volunteers could not arrest anyone, but they would alert police if they discovered criminal activity. Members were local to the area and known in the community, embodying the aspirations of community policing often raised to this day in conversations about reform, a dream which has proven difficult to realize in practice due to the threat of violence which lies behind the badge. In contrast, the civic patrol organized teen dances every other Friday night. Martin told the Hartford Courant that a key peace-keeping strategy in Hartford should be extending city recreational facility hours until 11 pm, an extra two hours. He also advocated for police racial sensitivity training and a civilian review board, both of which were heavily resisted by the union.

After Hansley’s death, Martin set up appointments to meet with members of each police shift and explain the OCP’s work in order to facilitate stronger communication. The civic patrol had not been informed of the increase in purse snatchings before the shooting, or the formation of the plainclothes unit. The fire department provided an example of effective cooperation; they would send the OCP bulletins with areas and times of day in which they received high numbers of false alarms. The patrol would maintain an active presence in these areas, and rates of false alarms went down.

Gary “Mike” Hansley Newspaper Coverage

- March 15, 1970: HC “Fleeing Suspect Shot to Death”

- March 16, 1970: HC “Autopsy Is Performed On Body of Slain Youth”

- March 17, 1970: HC “Police Shot Hit Youth in Heart”

- March 18, 1970: HC “Officer’s Suspension Asked in Shooting”

- March 19, 1970: HC “Group Says Policeman Violated Own Guideline”

- March 20, 1970: HC “Vaughan Defends Action of Policeman”

- March 21, 1970: HC “Protesters Parade In Front of Station”

- March 21, 1970: HC “Mayor Calls Talk on Shooting”

- March 21, 1970: HC “Union Head Defends Policeman in Death”

- March 21, 1970: HC “Moderation Urged in Rallying Over Black Youth’s Shooting”

- March 22, 1970: HC “Meeting Fails to Quell Storm Over Fatal Shooting of Youth”

- March 23, 1970: HC “Policeman in Slaying Backed by Mayor”

- March 24, 1970: HC, “Action Asked on Shooting”

- March 25, 1970: HC “Officials Ask More Information in Shooting”

- March 25, 1970: HC “Civic Patrol Accuses Police of Non-Cooperation Before Hansley Death”

- March 25, 1970: HC “Mayor Gets Support For Police Stand”

- March 26, 1970: HC “Breaking Laws Is Asking for Trouble”

- March 26, 1970: HC “Law Experts To Discuss Guidelines”

- March 26, 1970: HC, “Firearms Controversy Still Hot”

- March 28, 1970: HS “Community Leaders Say Shooting ‘Violated Present Guidelines’”

- March 29, 1970: HC “Of Firearms And Policemen: Debate Deepens”

- March 29, 1970: HC “Vague Guidelines Point Police Guns”

- March 29, 1970: HC “Who Sets Police Guidelines?”

- March 31, 1970: HC “Spanish Coalition Shows Concern In Hansley Case”

- March 31, 1970: HC “Protesters Parade Through Churches”

- April 2, 1970: HC “Detective Takes Note Of Support”

- April 2, 1970: HC “North End Group Selects Own Slate”

- April 3, 1970: HC “State’s Police Chiefs Say Guns Necessary to Combat Crime in Streets”

- April 4, 1970: HC “50 Sign Protest Calling Shootings By Police A Game”

- April 4, 1970: HS “Pickets Protest Shooting Death”

- April 11, 1970: HS “Protest Group Invades City Hall”

- April 11, 1970: HS “Group To Boycott Downtown Stores”

- April 11, 1970: HS “Community Opinions: What steps should the black community take in view of the recent killings?”

- May 8, 1970: HC “Policeman Cleared In Hansley Shooting”

- March 13, 1971: HC “Policeman Faces $300,000 Law Suit”

- March 20, 1971: HS “Police-Shooting Victim’s Family Files Law Suit”

Notes

1. Stephen Parks, “Fleeing Suspect Shot to Death,” Hartford Courant, March 15, 1970, Proquest.

2. “Spanish Coalition Shows Concern In Hansley Case,” Hartford Courant, March 31, 1970, ProQuest.

3. “Officer’s Suspension Asked in Shooting,” Hartford Courant, March 18, 1970, ProQuest.

4. “Community Opinions: What Steps Should the Black Community Take in View of the Recent Killings?” Hartford Star, April 11, 1970.

5. “Police-Shooting Victim’s Family Files Law Suit,” Hartford Star, March 20, 1971.

6. Janet Anderson, “Civic Patrol Accuses Police of Non-Cooperation Before Hansley Death,” March 25, 1970, ProQuest.