Incident: On Friday August 29, 1969, at 12:30 pm, Officer Keith G. Marshall saw a car that matched the description of one stolen the night before in Hartford. It was driven by sixteen-year-old Dennis Jones and two companions, Raymond Arter and Russell Seals Jr, none of whom were armed. Officer Marshall followed the car into Hartford and a chase began at speeds up to eighty miles per hour, during which Marshall used neither sirens nor red lights. Eventually other police vehicles joined the chase and Jones hit a bump in the road, spinning out. As the boys ran from the car, Officer Marshall yelled at them to halt. They did not stop, so he shot Jones aiming for the legs, but the bullet entered the boy’s left side, just above the waistline. Officer Marshall later claimed that he did not know Jones was a minor until he approached him on the ground and asked if he had been hit. Jones was pronounced dead on arrival at the hospital. He was not identified until that night, when his mother called police headquarters to report her son missing. The next day, West Hartford Chief William P. Rush made a statement regarding the horrific incident in which he defended Marshall. According to Chief Rush, the officer had just been following police guidelines.

Coroner’s Report: County Coroner Irving Aronson issued a report officially absolving Marshall of blame on October 18th; Connecticut court precedent from the case Martyn v. Donlin (1964) allowed policemen to shoot in order to apprehend fleeing felons. In that case, the jury ruled in favor of Officer Robert Donlin, who had killed John Martyn while chasing him from what he believed to be a stolen car—a felony offense. Martyn v. Donlin set the precedent that in addition to self-defense, an officer may use deadly force to prevent the escape of a felony suspect. This was seen to follow from Connecticut common law. 1

Despite its outcome, the coroner’s report was not unilaterally supportive of police use of firearms. In an aside, Aronson warned “one fact the police officer always should bear in mind in making his decision (whether or not to shoot) is that if he uses his gun, he is going to kill somebody.”2 Aronson elaborated that police pistols are only deemed accurate towards “stationary targets” at close range, whereas Jones was moving at approximately 125 feet away; “therefore the police officer should not think that he is going to inflict a non-fatal wound by shooting at an arm or leg. He should fully expect the shot to be fatal.”3 At the same time, Aronson expressed sympathy with Marshall’s need to make a snap decision.

The report pointed out an eerily similar case two years prior; a Glastonbury officer shot and killed sixteen-year-old Raffael Ratti after a high-speed chase in a stolen car. Ratti and Jones suffered precisely the same fatal injury. The Glastonbury officer had been absolved of guilt as well, but Ratti’s estate was later awarded $10,000 in damages after suing.

Community Response: The day after Jones’ death, L. Howard Nichol—chairman for the Greater Hartford chapter of the ACLU—released a statement condemning Officer Marshall’s actions and arguing that a suspect fleeing a stolen car should not be shot since they would only receive a short jail sentence anyway. Further, Nichol was upset by the “lack of concern that the moral, spiritual and political leaders of the Greater Hartford area had shown about the loss of life incurred by the use of legal force on the part of policemen.”4

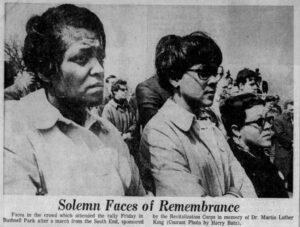

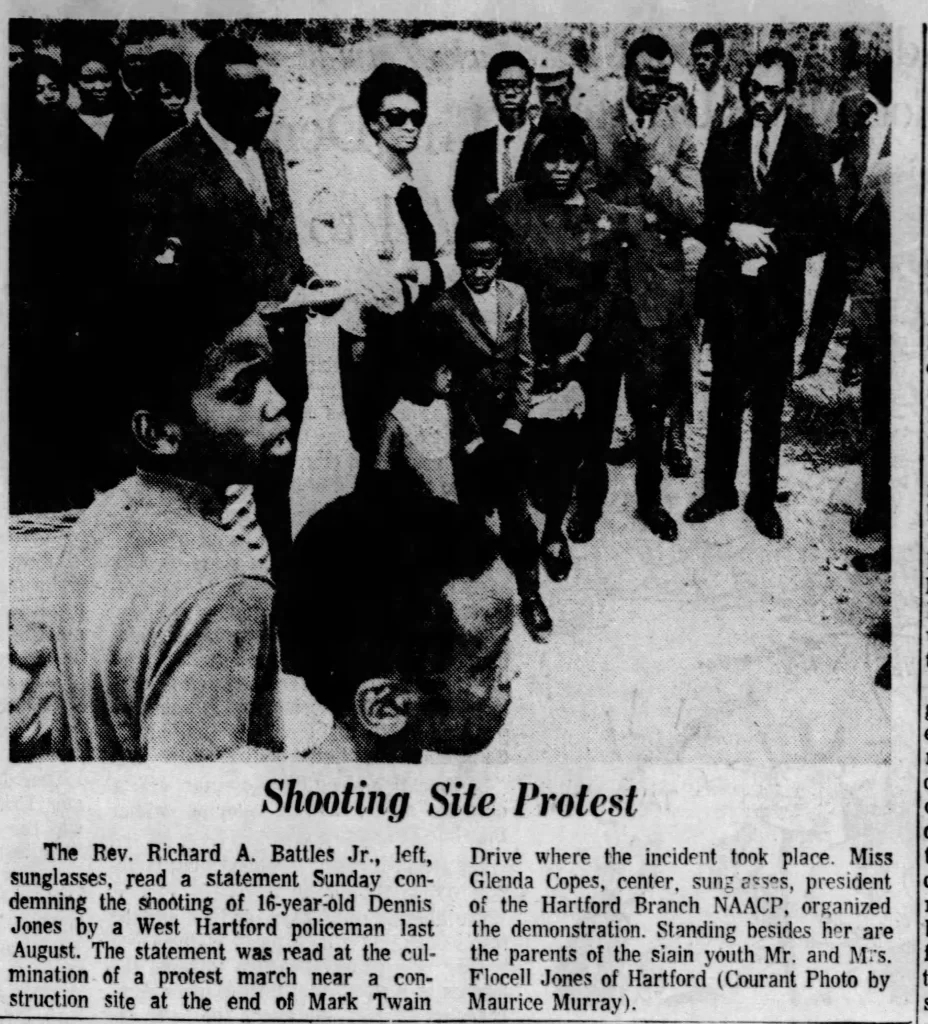

Jones’ funeral was held September 3rd at the Mount Olive Baptist Church. Reverend Richard A. Battles spoke, demanding the police reopen the investigation into the shooting, since it had lasted just one day. Glenda Copes, President of the Hartford NAACP chapter and an original plaintiff in Cintron v. Vaughan, organized a memorial march for Jones on October 19th; “We will be honoring Dennis Jones’ memory, and also calling attention to the conditions that brought about his death.”5 The march ended up falling just one day after County Coroner Aronson absolved Marshall of negligence. Around fifty people joined, and the group ended up at Mount Olive for an additional memorial service. Charlotte Kitowski, a member of the local ACLU who spoke to the Hartford Courant at Jones’ memorial march, said “Policemen use only so much force as they think the community wants them to. The community must therefore set up the guidelines and show how much it is prepared to accept.”6

That December, state NAACP director William C. Jones—along with representatives of the Connecticut Civil Liberties Union and other community members—met with West Hartford officials to discuss the department’s guidelines regarding firearms use. The town subsequently issued a directive to its police department reminding them to be sparing with force and to exhaust all other means of apprehending a suspect before reaching for the gun. The directive also placed an additional limit on police use of firearms beyond that set in Martyn v. Donlin: “In no case shall a member of the Department shoot at a person whose only known or apparent offense is a misdemeanor or the theft of a motor vehicle.”7

Lawsuit: In April 1970, Dennis’ mother Virginia Jones sued the town of West Hartford for $200,000 in negligence damages (under the name of her husband, Flozell Jones). She also made a civil rights claim, and alleged that her son’s constitutional rights were violated. In addition to the town, the suit named three other defendants: Officer Marshall, West Hartford town manager Richard H. Custer, and Police Chief Rush. Jones was represented by Uconn Law School’s Louis I. Parley and the ACLU’s Bruce Mayor, who went on to represent the estate of Efrain Gonzalez (see Efrain Gonzalez). The federal suit was trying to overturn the 1964 precedent set in Martyn v. Donlin. The plaintiffs aimed to change the rule such that an officer could only use deadly force if the felony suspect had committed a crime of bodily injury, following the American Law Institute’s 1962 model penal code.8 Deadly force for a property crime, they argued, is unconstitutional and barbaric.

Jones challenged West Hartford’s guidelines on police use of firearms, and also argued that Marshall’s actions violated the policies laid out in West Hartford’s police training bulletin as well as federal task force guidelines on the use of deadly force. The suit took issue with the fact that Marshall had not used sirens in his initial chase, had not given a warning shot before firing at Jones, and had not tried any other method of apprehension before resorting to the pistol. In addition to damages and the constitutional challenge, the suit requested that the town make public all records of police safeguards regulating the use of weapons during arrest, create a safe weapons training program, and invest in non-lethal equipment to stop fleeing suspects.

The lawsuit garnered both positive and negative interest in the Hartford area. Jones made a statement assuring the public that she had first conceived of the suit soon after her son was killed, and that it was not a response to the highly visible controversy over police shootings that had arisen in the Spring of 1970, either responding to or predicting such an accusation. Fannie Wagner, resident of West Hartford, wrote a letter to the Hartford Courant in March of 1971 voicing her hope for the Jones trial as a “test case… which may establish the principle that wrong-doing by police is no more justified than wrong-doing by anyone else.”9 Perhaps Jones was encouraged by the success of the lawsuit filed by Rafael Ratti’s family after he was killed in similar circumstances (see above).

In July of 1971, US district Judge M. Joseph Blumenfeld dismissed Custer, Rush and the town of West Hartford as defendants, leaving only Officer Marshall. There was no further movement until May 1974, when both parties agreed to a stipulated set of facts instead of a trial. On October 10, 1974, Judge Blumenfeld—who one year earlier decided Cintron v. Vaughan via consent decree—sided with Marshall. “While there is no doubt that a contrary view exists and indeed has much to support it, it is not the prerogative of this Court to judge the constitutionality of state laws on policy grounds alone, as the plaintiff would essentially have it do. If the plaintiff believes the state law on the use of deadly force to effect an arrest to be unjust or overly harsh, it is to the legislature, and not the federal courts, that he must turn.”10 The plaintiffs appealed in 1975, arguing that the civil rights claim was a matter of federal law that transcended the state level, and that the common law rule was outdated and had been disproven by scholars. The ruling was upheld in 1975. Marshall had since switched careers and joined the fire department. The parallels between the deaths of Dennis Jones and Rafael Ratti ended here, as Jones’ family received nothing as recompense for their tragedy. Ultimately, the law is built to recognize only those mistakes which are aberrant to its structural function; the death of a white teenager is a coherent mistake, whereas the killing of a Black teenager indicates a system working as it was intended.

Dennis Jones Newspaper Coverage

- August 29, 1969: HC “Youth Is Shot, Killed in Chase Of Stolen Car”

- August 31, 1969: HC “ACLU Criticizes Shooting of Boy”

- September 4, 1969: HC “Guidelines Exist On Weapons, Says Chief Rush”

- September 4, 1969: HC “Demand for New Probe Made at Youth’s Funeral”

- September 10, 1969: HC “Jones Case ‘Cannot Rest’”

- September 10, 1969: HC “Wants Law Policies Re-Examined”

- September 12, 1969: HC “Committee Deplores ‘Reliance on Guns’”

- September 14, 1969: HC “Feels Youths Must ‘Take Consequences’”

- September 14, 1969: HC “Believes Policemen Deserve Respect”

- September 20, 1969: HC “Town Council To Get Report On Shooting”

- September 24, 1969: HC “Council Awaits Coroner’s Inquest On Shooting of Youth by Police”

- September 24, 1969: HC “Sees Shooting as ‘Unfortunate Accident’”

- October 17, 1969: HC “Memorial March Set for Slain Youth”

- October 19, 1969: HC “Policeman Absolved In Fatal Shooting”

- October 20, 1969: HC “Small Group Commemorates Death Of Youth Slain Fleeing Policeman”

- Photo

- October 21, 1969: HC “The Coroner Reports On a Sad Incident”

- December 24, 1969: HS “Shoot-to-kill? Rule Studied in Wake of ‘Senseless’ Slaying”

- April 25, 1970: HC “West Hartford Sued In Slaying of Youth”

- March 21, 1971: HC “Test Case”

- July 1, 1971: HC “Policeman Faces Suit Alone”

- May 12, 1974: HC “Judge Weighs Claim In Shooting Death”

- October 10, 1974: HC “Policeman Ruled Right in Shooting”

Notes

1. Martyn v. Donlin, 198 A.2d 700, 151 (Conn. 402, 2000). “But the use of a means, or of force, likely to cause death, as was the case here, is privileged only if the arrest was for a felony and the force used was reasonably believed to be necessary to effect that arrest.. . . An officer in using deadly force for this purpose must act in good faith. He must have actually believed, and also have had reasonable cause to believe, that it was necessary under the circumstances to use deadly force to make the arrest.”

2. “The Coroner Reports On a Sad Incident,” Hartford Courant, October 21, 1969, ProQuest.

3. Gerald J. Demeusy, “Policeman Absolved In Fatal Shooting,” Hartford Courant, October 19, 1969, ProQuest.

4. “ACLU Criticizes Shooting of Boy,” Hartford Courant, August 31, 1969, ProQuest.

5. “The Coroner Reports On a Sad Incident.”

6. Calvin de Grasse, “Small Group Commemorates Death Of Youth Slain Fleeing Policeman,” Hartford Courant, October 20, 1969, ProQuest.

7. “Shoot-to-kill? Rule Studied in Wake of ‘Senseless’ Slaying,” Hartford Star, December 24, 1969.

8. “Section 3.07. Use of Force in Law Enforcement,” Model Penal Code, American Law Institute, May 24, 1962. The influential code, sponsored by the US Department of Justice, read; “The use of deadly force is not justifiable under this Section unless: … (i) the arrest is for a felony; and (ii) the person effecting the arrest is authorized to act as a peace officer or is assisting a person whom he believes to be authorized to act as a peace officer; and (iii) the actor believes that the force employed creates no substantial risk of injury to innocent persons; and (iv) the actor believes that: (1) the crime for which the arrest is made involved conduct including the use or threatened use of deadly force; or (2) there is a substantial risk that the person to be arrested will cause death or serious bodily harm if his apprehension is delayed.”

9.Fannie Wagner, “Test Case,” Hartford Courant, March 21, 1971, ProQuest.