City Council Committee on Police Use of Firearms

Context: Abraham Rodriguez’s death (see above) was the third police shooting in Hartford within a month, and the second fatality. On March 14th, 1970, nineteen-year-old Gary Hansley was killed by plainclothes Officer Elden Thibodeau (see above, Gary “Mike” Hansley). On March 31st, William Casey, thirty nine, was shot four times outside his home by Officer David Quirk (see above, William Casey). Both victims were Black. The officers were found to be acting within department rules, which allow them to shoot in self-defense, or to stop a felon from fleeing. After Hansley’s death, several mass rallies were held and community leaders demanded more strict guidelines on police use of guns. At a city council meeting on March 24th, Mrs. Regina Brown, a youth counselor at Horace Bushnell Church, read three community resolutions that had arisen through meetings and rallies at Horace Bushnell Church (see above: Gary “Mike” Hansley; Community Response).

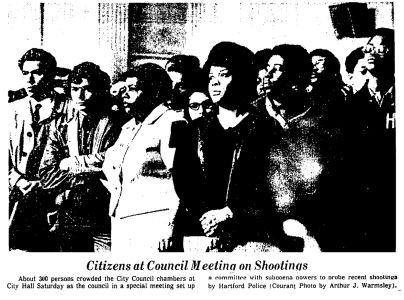

Committee Formation: After Rodriguez’ killing on April 1st, tensions grew so high that the city council convened a special Saturday meeting to vote on the creation of a committee with subpoena powers to investigate police use of firearms. The committee, made up of three council members, passed six-three under the name “Special Council Committee de Investigation of Shootings and of Existing Police Guidelines for Use of Force in Connection Therewith.” The chairman was deputy mayor George Athanson, joined by Allyn Martin and minority leader Roger Ladd. Ladd had voted against the committee’s formation. Hundreds of people attended the Saturday meeting, many wearing black armbands in support of the victims and for the second anniversary of MLK’s assassination. Representatives of several Puerto Rican organizations in Hartford felt that the committee did not go far enough, and recommended steps for further public engagement and accountability. It had been previously ruled on April 2nd that city council would have the power to change police guidelines; however, the investigative committee would only have the power to recommend such guidelines. Nonetheless, the whole effort was faced with enormous pushback from police and their supporters.

Police Resistance: HPD officers held a mass midnight meeting after the council decision and voiced their anger. Talk of a strike was discouraged by union lawyer Joseph Fazzano, but he advised the department to “resist subpoenas and do not present witnesses… It’s going to take courage and the belief that you as policemen have done nothing wrong. Unlike the people who have threatened my life and others we’re not going to be irresponsible. We’re needed on the street.”1

The union ended up successfully obtaining a temporary injunction over the committee’s activity. After an eleven-hour bargaining session, an agreement was reached stating that the committee would continue to hold hearings but would not have the power to subpoena; and union members would testify voluntarily for the committee, breaking with union policy to never testify even if subpoenaed. It was also formally acknowledged that the committee would not have the authority to change police guidelines, even though it never was so empowered in the first place. Ultimately, the compromise was a win for the union because the council was able to put off legal inquiry into whether the police would be controlled by city council or by City Manager Elisha Freedman, who was close with Chief Vaughan and other police officials. This uncertainty would embolden the union to push for its officers’ freedom from disciplinary action for a long time.

Despite the police union’s resolution to resist the investigation, the Connecticut Guardians—an organization of fifty Black Hartford police officers (see below)—issued a statement in support of the committee. The Guardians’ president, Alfred Cicero, said they would cooperate fully with all proceedings. Members of the Guardians were also members of the police union and their internal vote was not unanimous, but all agreed to testify if asked.

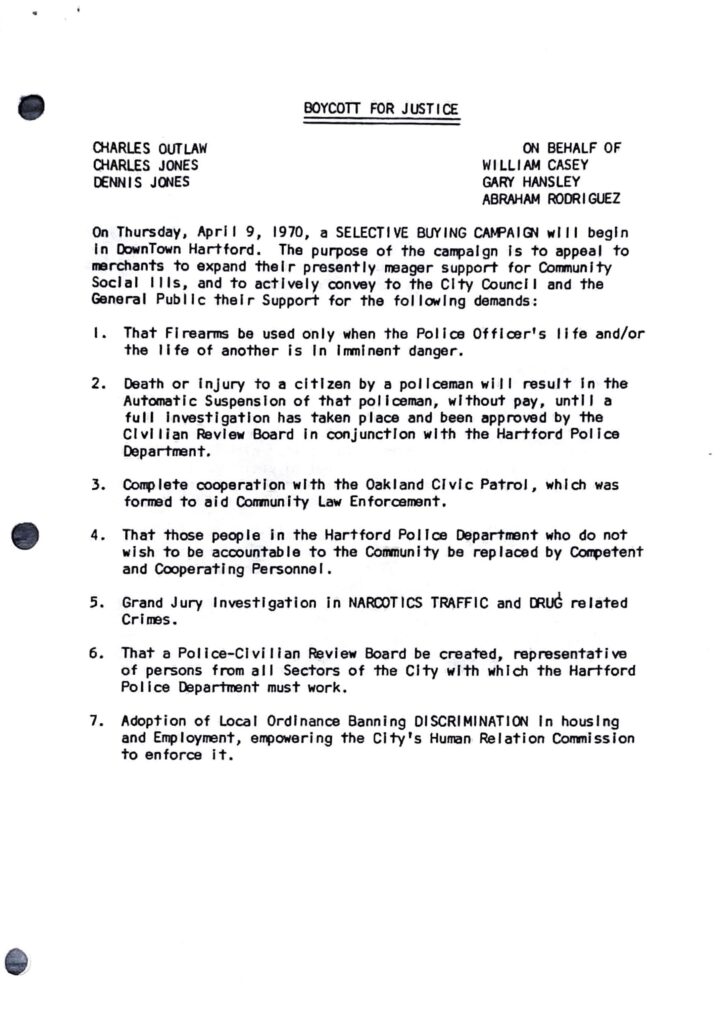

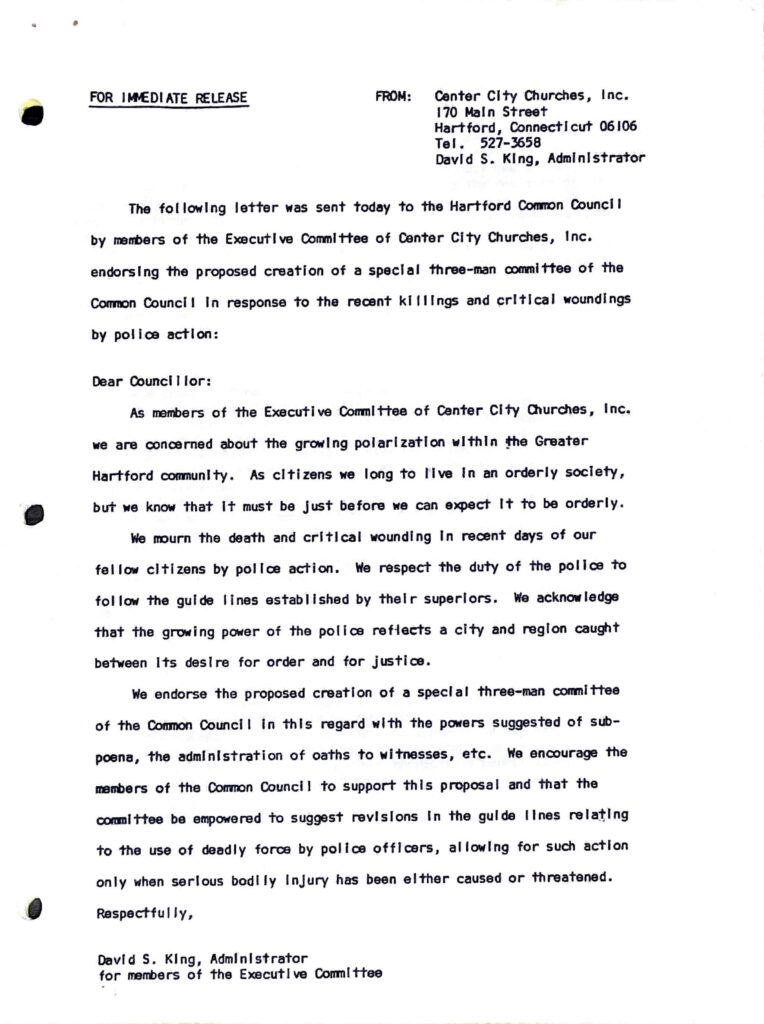

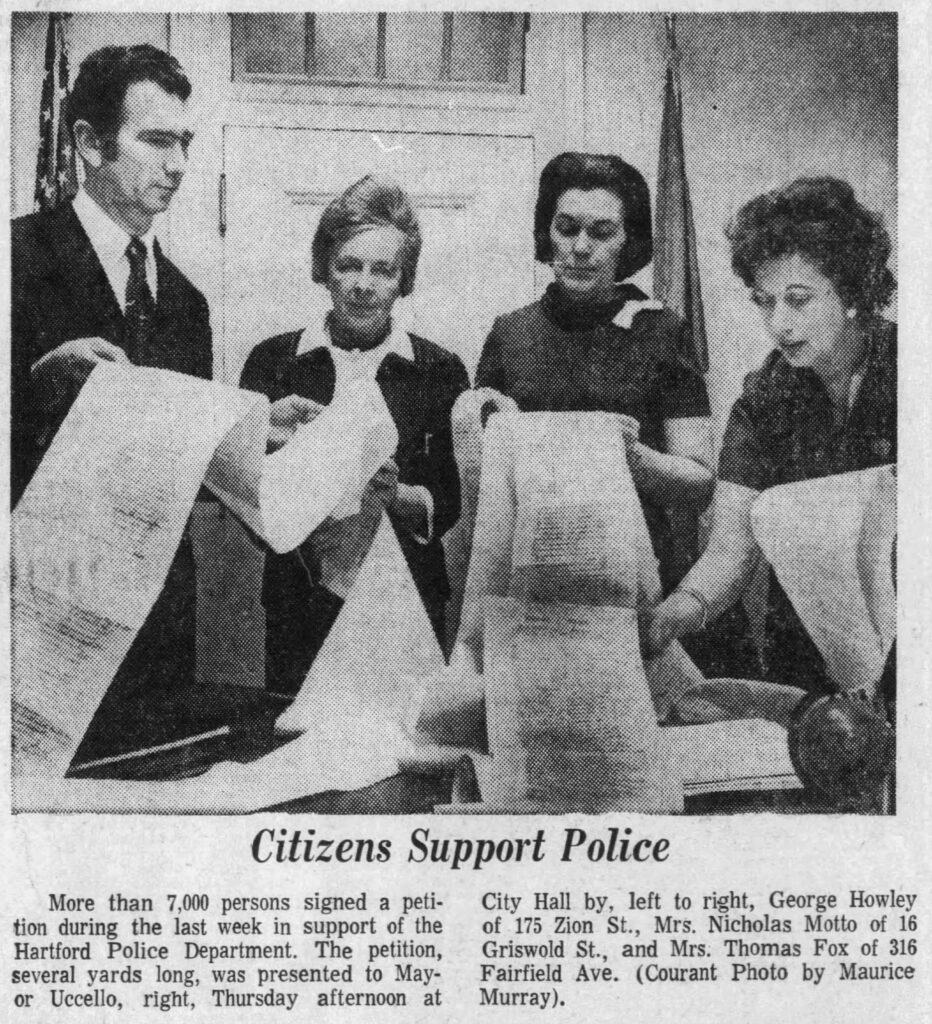

Organizing: There were formidable local organizing efforts on both sides of the debate. A new organization called the Committee for the Strong Enforcement of Law and Order, made up of Hartford’s police-adjacent community, collected a 7,000-signature petition condemning the investigation. At the same time, a shopper’s boycott called for shoppers on a busy commercial street to refrain from entering any business that did not voice support for the council investigation. Hartford clergymen released a statement calling for increased police accountability;

The shootings of the past weeks raise basic questions. Should not the police department like any other institution be accountable for its actions to an impartial review board? Fear of many kinds and poor judgment can be part of any man’s life. To the extent that it might be present, what can be done to diminish it in the lives of those who hold such a unique responsibility in the community?2

On April 1st, a North End group released their own slate of five candidates to represent the seventh assembly district on the Democratic Council Committee. This committee had already released the official slate, but North End residents felt it was inadequate “because the present town committee is not truly representative of the seventh district… we will no longer stand for these committeemen to re-elect themselves year after year.”3 The people’s slate included Herbert Sutton, Regina Brown, Peter Williams, Bruce Adams, and Sharon Courts. Alongside the city council committee debate, this move came in the same wave of organizing towards improved conditions in the North End.

Hearings: The committee on police use of deadly force started hearing testimony on April 15th, 1970. Arguing against stricter guidelines, Chief Vaughan said that the risk of shooting is an effective deterrent against crime, disturbingly pointing to the drop in purse thefts since Hansley’s murder. Many police officers as well as Attorney Fazzano testified in a similar vein, arguing for the necessity of shooting to prevent escape and rejecting the prospect of any form of civilian review. The police and adjacent community felt that the committee’s purpose was to prevent police from doing their jobs.

On the other hand, many people gave powerful testimony for stricter guidelines. Officer Arnold Martin, who also taught at a local high school, spoke about the need for psychological evaluation of new recruits. Regina Brown, an active voice of the North End in local politics (pictured above, see Gary “Mike” Hansley), named the main issue at stake: whether police are accountable to the community or only to themselves. Jon O. Newman, former US Attorney for Connecticut, told the committee that curbing crime should not center on firearms, specifically the single method of shooting to stop a fleeing felon. He argued that the deterrence argument is severely flawed. Strengthening this point, Samuel G. Chapman—who had been a police chief in several states and by then a professor at the University of Oklahoma—said that police officers are trained to shoot to kill, and that shooting to wound only happens in movies. Attorney Sydney Schulman also gave powerful testimony towards better police practices: “The question before this committee is not a matter of law and order but of abuse of police power,” he said.4

Arthur L. Green, director of the Connecticut Commission on Human Rights and Opportunities, testified that recruitment, training and individual attitudes determine police behavior more than written rule: “It is not the guidelines that is the problem. We think the problem is how they are used, the attitudes of everyone involved from the top city officials on down to the newest recruit. That is important here.”5 Green was actively involved in Hartford police reform efforts, and would submit a proposal for a civilian review board and independent review of complaints the next year. Despite coming from a place critical of police practices, implying that the guidelines are the least of the problem compared to a wider culture of hostile governance, Green’s sober assessment ended up providing a basis for agreement with city officials who aimed to maintain the status quo. In a split-second decision, as many people pointed out on both sides of the issue, a cop is likely not going to be concerned with guidelines, strict or not.

Committee Results: Since city council had been given the power to change police guidelines, the committee’s reports would have a significant effect on such a decision. Ultimately, however, the 721-page transcript generated by the hearings was filled mostly with police testimony. The committee seemed to value their opinions more than those of outside experts who offered critiques of deadly force, some of whom had been flown in to testify. The committee voted two to one to recommend no change in guidelines concerning use of force. They argued instead that change should come from recruit training, in-service training, and community relations, and pointed to recent developments in these three areas that signify progress. After presenting the quote from Arthur Green included above, the committee majority wrote: “Your committee, therefore, agrees with Mr. Green that no matter what the guidelines, whether they are made more loose, or more restrictive, when the police officer exercises judgment in a split-second what really comes into play is his training, his deportment, his attitude, his intelligence, good judgment, discipline as well as self-discipline.”6 It is hard to deny this statement, but it does not address accountability. Even if a stricter guideline has no bearing on an officer’s split-second decision, it will enable them to face consequences for excessive force, and therefore make Hartford safer for its Black and Puerto Rican citizens over time. Unfortunately, those whose voices had the most power during these negotiations felt that police accountability endangered the public more than liberal use of firearms; this question, of course, depends on which public one is talking about, a veiled subtext that cuts deep into the heart of Hartford politics in the 1970s.

Dr. Allyn A. Martin provided the dissenting vote in the committee’s decision, and wrote an impassioned minority report which would become a canonical text within Hartford’s police accountability discourse over the next decades. Martin, one of the only Black members of Hartford’s city council in 1970, was an outspoken critic of excessive policing. In 1969, he had been the only council member to vote against a resolution requesting swift and severe punishment for citizens arrested during the summer civil disturbances: “It is foolish to think punishment will prevent riots in this combustible society… it is not true that jailing people will prevent riots.” In his minority report for the committee on deadly force, Martin emphasized that police procedure should reflect public opinion and hold the confidence of the people it aims to protect. Countering the majority argument that the police officer does not think of guidelines during a split-second decision, Martin proposed:

Ultimately, the officer must, in any given situation, ask himself one question; ‘Am I justified in killing?’ If the answer to this question is in doubt, he should not fire … It would be well if Police and Community took cognizance of the fact that ‘policy for a gun shooting death is easily rewritten. Human life, once taken, lingers only in photographs, mementoes, epitaphs and newspaper accounts.’7

It came as no surprise to the insightful Hartford Courant reporter Theodore Driscoll that no new guidelines were taken up (see below, quote from Driscoll’s “Deadly-Force Study Dead-Ends”). In an article published November 8, 1970, Driscoll lays out the many crucial issues that the committee failed to investigate. For instance, police policy required that each officer keep eighteen bullets at a time and fill out paperwork explaining each discharge before they can replace them; however, it was common knowledge that police often used their own ammunition on duty, sidestepping this form of accountability. The committee did not seem to care. There were many more egregious oversights as well, calling the entire effort into question; was it all a performance of accountability meant to ease tensions during a season of uprisings?

City Council Deadly Force Committee Newspaper Coverage

- March 21, 1970: HC “Mayor Calls Talk on Shooting”

- March 23, 1970: HC “Policeman in Slaying Backed by Mayor”

- March 24, 1970: HC, “Action Asked on Shooting”

- March 26, 1970: HC, “Firearms Controversy Still Hot”

- March 29, 1970: HC “Who Sets Police Guidelines?”

- April 2, 1970: HC “Council Can Set Guides On Firearms”

- April 3, 1970: HC, “Citizens Meet Over Shootings”

- April 4, 1970: HC, “Policeman Faces Probe Over Shooting of Youth: Violation Of Rules At Issue”

- April 4, 1970: HC “Judo Suggested For Police Use”

- April 5, 1970: HC, “Shooting Probe Committee Appointed: Policemen Hear Call To Resist Anger Voiced At Meeting”

- April 6, 1970: HC “Police Try to Halt Probe By Seeking Injunction: Union Goes To Court Today”

- April 7, 1970: HC “Black Policemen Favor City Probe: Vote Defies Resolution Of Union”

- April 8, 1970: HC “Police Union Test of Council To Get Court Hearing Today”

- April 9, 1970: HC “Council Probe Of Police Set For Friday: Guideline Change Is Forbidden”

- April 9, 1970: HC “Text of Agreement by City, Police” p much in my notes from prev article but good to have real text

- April 10, 1970: HC, “City Opening Inquiry”

- April 10, 1970: HC, “Ministers Support Police Review Unit”

- April 11, 1970: HC “Council Committee Closes Door To Draw Up Police Probe Rules”

- April 12, 1970: HC “Deadly Force a Public Matter”

- April 15, 1970: HC “Chief Vaughan to Testify First As Police Probe Opens Today”

- April 16, 1970: HC “Purse Thefts Drop”

- April 18, 1970: HC “Police Probe Aim Seen Misinterpreted”

- April 23, 1970: HC “Improper Bullet Used”

- April 23, 1970: HC “Mayor Opposes Probe Of Police Shootings”

- April 24, 1970: HC “Counsel Rules Guidelines Can be Set”

- May 1, 1970: HC “Best Policy Called ‘Don’t Run’”

- May 3, 1970: HC “Tighter Police Guidelines Unlikely”

- May 5, 1970: HC “3 Policemen Suspended for Shooting”

- May 6, 1970: HC “Petition Backs Police Actions”

- May 7 1970: HC “Officer Qualifies Use of Force”

- May 8, 1970: HC “Training, Attitude Said to Influence Police”

- May 13, 1970: HC “False Issues Rapped Before Shooting Probe”

- May 14, 1970: HC “Former Police Chief Stresses Stricter Guidelines”

- June 26, 1970: HC “Council Group Holds Long Closed Session”

- June 28, 1970: HC “Guideline Report Due Soon”

- August 20, 1970: HC “Parley to Consider Police Use of Guns”

- August 21, 1970: HC “Guidelines on Firearms Discussed”

- August 30, 1970: HC “Police Arms Probe Mired in Guidelines”

- September 2, 1970: HC “Vaughan Joins in Defense of Suspension”

- September 6, 1970: HC “Police Compromise in Bloom”

- November 8, 1970: HC “Deadly-Force Study Dead-Ends”

- January 17, 1971: HC “Is Outside Probe of Police Necessary?”

Notable excerpts from Courant reporter Theodore A. Driscoll’s coverage of police/council disputes:

March 29, 1970: HC “Who Sets Police Guidelines?”

“As was discussed before the city council’s meeting of the whole wednesday, it was unclear what powers the council and the city manager have in these matters. It was suggested that they have none. But if they do not control the police, who does. If it is the police themselves, then we have removed these matters from those capable of making detached judgements. Police are no more equipped to set their own guidelines than generals are to make foreign policy. This is not a condemnation of the police or of police judgement. Anyone who has ever seen a riot, with its indiscriminate hatred and violence, or accompanied the gentlest and most humane of the policemen making his rounds in a hostile community would not suggest that police can be objective in these matters. How could they be. It is as absurd, and potentially dangerous, to let police set policy for their conduct as it would be to let criminals or rioters make the laws. There is growing opposition within the police to any civilian interference and concurrently a public clamor for law and order.”

April 12, 1970: HC “Deadly Force a Public Matter”

“Many people suggest that even an inquiry into police conduct subverts efforts to make the streets safe and to curb the spiraling crime rate. Risking a layman’s intrusion into apparently sacrosanct matters, one might question whether the recent shootings will help these efforts.”

November 8, 1970: HC “Deadly-Force Study Dead-Ends”

“following this triumph April 9 the councilmen retired to Carbone’s restaurant and for the next several hours indulged themselves with exotic food and drink. There were reports of flaming dishes and delicate liqueurs. A bill for $145 was to be paid by Hartford’s taxpayers. Within the next several days the committee launched its probe of police guidelines. High police officials were deterred from their normal duties to give hours of testimony. Some policemen sacrificed their own self-interest and gave testimony certain to enrage their superiors. Citizens representing various groups in the city gave up their time to testify. Chapman was flown in from Oklahoma. The citizens of Hartford, no matter what their position on guidelines, might well inquire what all this has accomplished.”

Jan 17, 1971: HC “Is Outside Probe of Police Necessary?”

“Public spokesmen, one after another, told the committee only police could make proper rules for themselves. Laymen were somehow incapable of understanding the complexities of police work. To some city officials this was a rather baffling assertion. If anything, the public and public officials tend to credit policemen with being more professional, proficient and compassionate than many of them are. Most policemen, for instance, would readily admit privately that at least some of their colleagues are bunglers and bullies. Publicly, of course, they defend one another almost irrespective of the circumstances. The secrecy of the police, the passionate opposition to any outside scrutiny, has led some councilmen to wonder aloud, at least privately, what is being hidden. This secrecy becomes even more suspect when it is apparent that, at least in some respects, candor from the police would make their work much easier.”

Notes

1. “Shooting Probe Committee Appointed: Policemen Hear Call To Resist Anger Voiced At Meeting,” Hartford Courant, April 5, 1970, ProQuest.

2. William Cockerham, “Priests, Nuns Back Probe of Shootings,” Hartford Courant, April 8, 1970, ProQuest.

3. Janet Anderson, “North End Group Selects Own Slate,” Hartford Courant, April 2, 1970, ProQuest.

4. Theodore Driscoll, “False Issues Rapped Before Shooting Probe,” Hartford Courant, May 13, 1970, ProQuest.

5. Court of Common Council, “Majority Report of the Special Council Committee de Investigation of Shootings and of Existing Police Guidelines for Use of Force in Connection Therewith” (Hartford, CT, 1970), 4. Held by the Hartford History Center.

7. Allyn Martin, “Minority Report of the Special Council Committee de Investigation of Shootings and of Existing Police Guidelines for Use of Force in Connection Therewith” (Hartford. CT, 1970), 943. Held by the Hartford History Center.